If you want to make your blues guitar playing more varied and interesting, I would strongly recommend learning a a range of different blues turnarounds.

Since they were first used at the beginning of the 20th century amongst ragtime performers and Delta bluesmen, blues turnarounds have gone on to become one of the most distinctive elements of blues music.

They play an important role in the structure of the blues. They create a strong sense of movement at the end of a 12 bar blues progression. And in turn this helps to bring the progression back to its beginning.

As I will explain in more detail below, you can use blues turnarounds as either a rhythm or lead guitarist. You can play blues turnarounds using chords, single notes or a combination of both. And this gives you a whole range of opportunities to explore in your playing.

In addition, all of the techniques and skills you will develop when learning blues turnarounds are transferable. You can use them in other areas of your blues playing, to improve both your rhythm and lead playing.

In this article then, I will be covering a range of different turnaround ideas that you can use and build upon. And this will make you a better blues guitarist, regardless of whether you are playing in a band context or at home along to backing tracks.

With this in mind then, let’s get into it! Here is everything you need to know about blues turnarounds, as well as 10 examples to get you started creating your own ideas:

What are blues turnarounds?

Before we dive in and look at specific examples of blues turnarounds, I think it is important to first establish what blues turnarounds are, as well as how and why you might choose to use them in your playing.

To understand blues turnarounds properly, you first need to have an understanding of the 12 bar blues. Throughout the rest of this article I will be referring to the 12 bar blues and its structure.

So if this concept is new to you, then I would head over to my article ‘An Introduction To The 12 Bar Blues‘ before continuing here. There you will find everything you need to know about the 12 bar blues progression, and which chords feature within that progression.

Blues turnarounds typically appear at the end of the 12 bar blues progression. They create a sense of movement which brings the chord progression back to its beginning.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of blues turnarounds that you are likely to encounter. These are as follows:

Chordal blues turnarounds

The first, and arguably the most common type of blues turnaround is one that you are likely to have encountered already.

This is because – in the vast majority of 12 bar blues progressions – the final 4 bars act as a blues turnaround. Although this is not true of all 12 bar blues progressions, the final 4 bars of a typical 12 bar blues progression run as follows:

V | IV | I | V

In the key of A – which I will be using for all of the examples here – the V chord will typically be E7, the IV chord D7 and the I chord A7.

These chords, played in this order, form a type of blues turnaround. They create a strong sense of harmonic movement, and this drives us back to the beginning of the 12 bar progression.

Chances are then, you are familiar with this type of turnaround in its most simplistic form. And yet there are countless ways of changing this chordal turnaround to make it more interesting. I will cover a number of these in more detail below.

Single note blues turnarounds

The second type of turnaround, with which you might not be so familiar, is based around single notes. In a band context, this section is often played by the lead guitarist, usually at the same time that a rhythm guitarist or keyboard player is playing the chord based turnaround.

In contrast to the chordal turnaround however, this type of turnaround typically lasts for just 2 bars. This creates melodic movement which strengthens the pull back to the beginning of the 12 bar blues progression.

It also creates a powerful focus point in the final 2 bars of the progression. This makes those 2 bars the most climatic point of the 12 bar blues progression. And this helps to ‘spice up’ the 12 bar progression.

In a practical playing context, it is likely that you will play a variety of different blues turnarounds. And the type of turnaround that is most appropriate for you to play will be partly determined by whether you are playing lead or rhythm guitar.

If you are the only guitarist (either in your band or playing alone at home) then you can use both, and combine elements of both the chordal and single note blues turnarounds.

Using blues turnarounds as introductions

It is also worth noting that blues turnarounds are often used as introductions. This is particularly common amongst lead guitarists, and those who play unaccompanied.

Robert Johnson was one of the early Delta bluesmen to use turnarounds as introductions. This is illustrated in some of his most famous songs, including ‘Walkin’ Blues‘, ‘Me and the Devil Blues‘ and ‘Sweet Home Chicago‘.

As is true of many of the techniques that Johnson and his fellow Delta bluesman pioneered, this has since become part of the fabric of the blues. This is particularly the case amongst acoustic blues guitarists and those playing country blues.

However it is also a technique that various electric guitarists have adopted. ‘Honey Bee‘ by Stevie Ray Vaughan, ‘Cannonball Shuffle‘ by Robben Ford, and ‘Before You Accuse Me (Take A Look At Yourself)‘ – originally played by Bo Diddley but later covered by Eric Clapton – all feature blues turnaround ideas in their introductions.

And this brings me to my final point. Use the examples below to give you initial ideas. These are not the only types of blues turnaround – so don’t feel compelled to learn or play them note for note. Instead, use them to give you ideas that you can build upon and adapt.

The fun is in experimenting! And by changing and building upon the blues turnarounds listed below, you can develop your own sound, whilst keeping your playing firmly rooted within the blues tradition.

So without further ado, let’s get into it! Here are 10 blues turnarounds you can use to add a bit of spice to your playing:

1.) Chromatic chordal turnarounds – pt. I

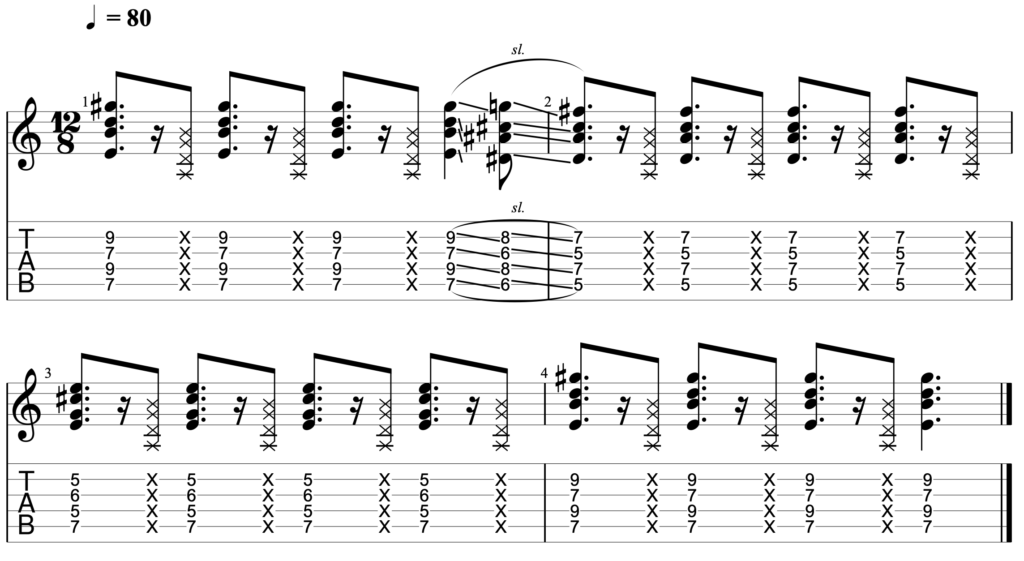

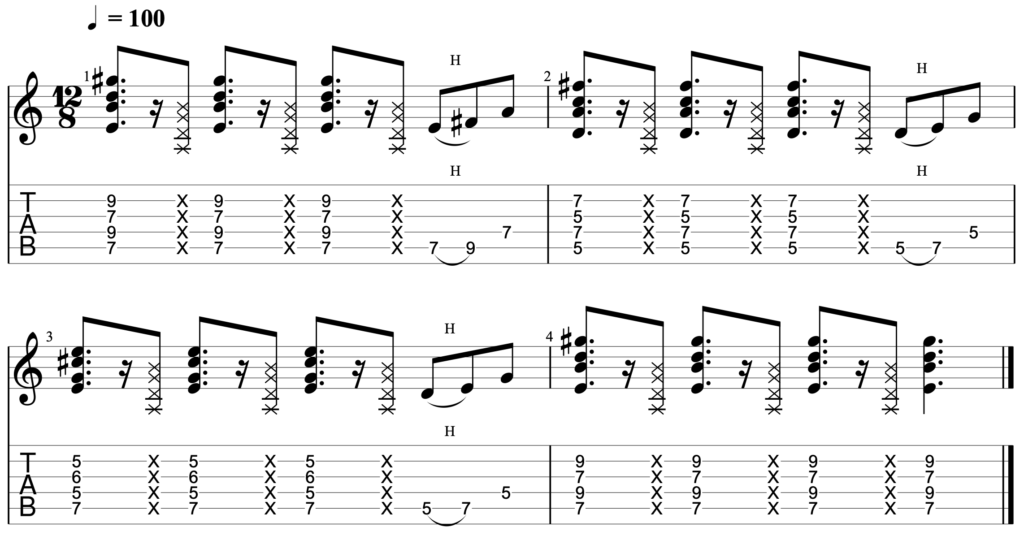

This first idea is one of the most simple and common ideas utilised in blues turnarounds. Yet despite its simplicity, it is also very effective. This is particularly the case if you want to add some life to a turnaround section, whilst still sitting back in the rhythm section. This is what this turnaround looks like:

And at 80 beats per minute (BPM), this is what it sounds like:

The only difference between this turnaround and the final 4 bars of a typical 12 bar blues progression, is that here the E7 and D7 chords are joined chromatically through the use of a slide.

This helps to reinforce the movement from the V chord to the IV chord in the progression, and adds a brief moment of chromaticism, which in turn gives that section a slightly jazzier feeling.

You will notice that in between each chord, I have placed a muted rake across the strings. In a real playing situation, I would not recommend playing these at the same volume you do the actual chords.

However by playing them quietly, you can stick in the groove and keep driving the rhythm, even in a slow blues context.

2.) Chromatic chordal turnarounds – Pt. II

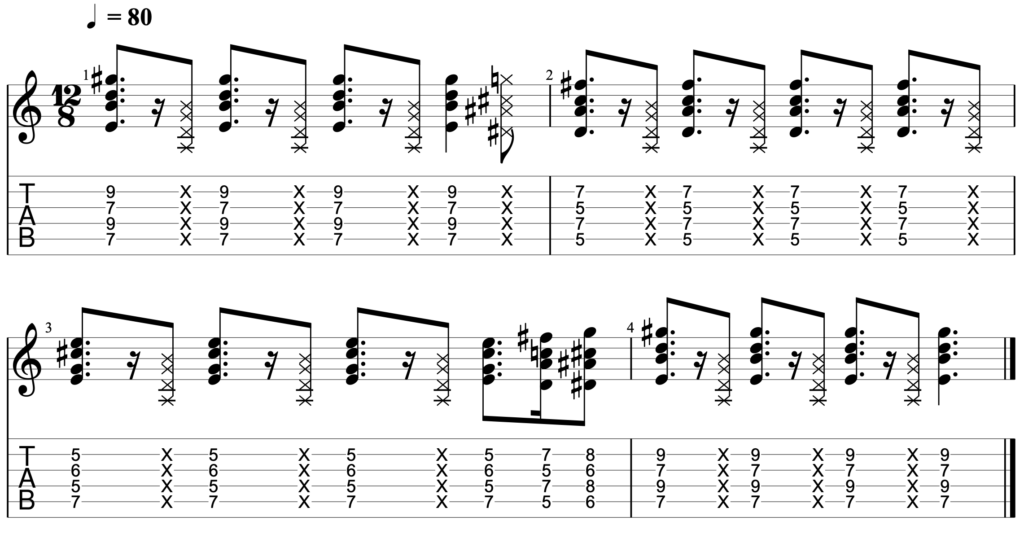

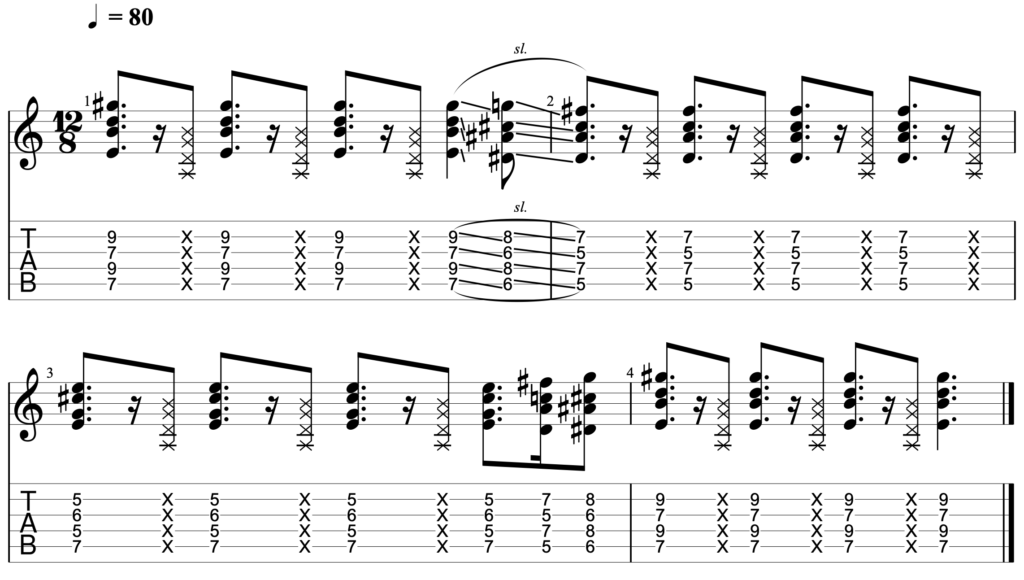

The turnaround in this second example is simply a reversal of the idea illustrated in the first. So instead of connecting the V and IV chords chromatically – here the I and V chords are connected chromatically in the final 2 bars. This is what this turnaround looks like:

And at 80 beats per minute (BPM), this is what it sounds like:

Here you have to make a quick switch from the I chord (A7) to the IV chord (D7), before moving chromatically to reach the V chord (E7). The other difference here is that the unlike the first example, the chords are not connected with a slide.

Rather, you play each chord individually. This is a small change, but it does add a different feel to the chord movement. It makes it sound a little more abrupt and staccato when compared with the movement illustrated above.

As in the first example, the movement in this turnaround is subtle. So if you want to change your blues turnaround more significantly, then you can combine these two ideas as follows:

At 80 BPM, this is what this turnaround sounds like:

This is just one example of how you can connect the chords in the final 4 bars of a 12 bar blues progression, using chromatics. But it is worth noting that there are innumerable different options available.

And if you like the sound of sliding into, out of, or between chords – then you can experiment with this idea throughout the 12 bar blues progression in its entirety. You don’t have to limit yourself to just the turnaround section.

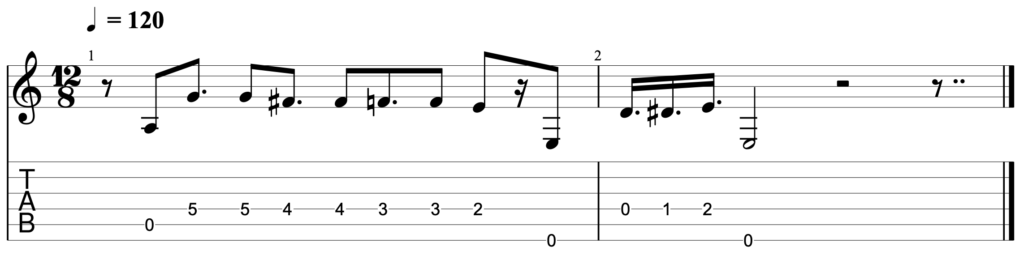

3.) Single note turnarounds

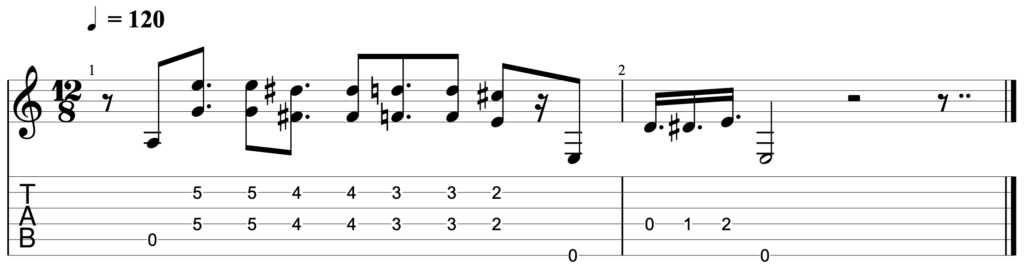

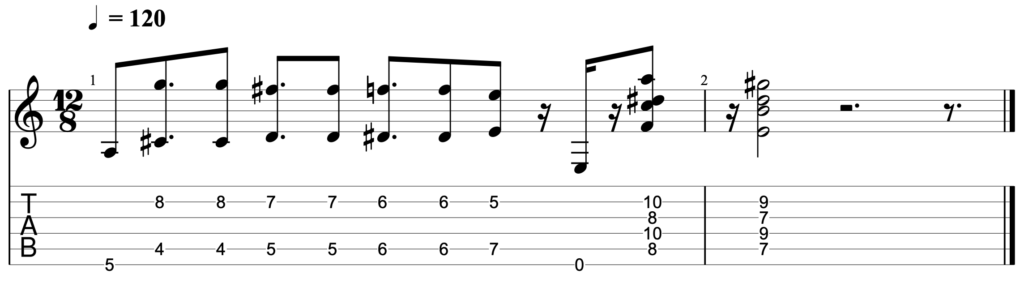

Unlike the first two examples, here the turnaround is played using single notes, rather than chords. This is one of the ‘classic’ blues turnarounds, and one with which you are likely to be familiar, even if you have not yet encountered it in your playing. This is what this turnaround looks like:

And at 120 BPM, this is what it sounds like:

This turnaround idea works well if you are playing in the ‘open position’. In other words, if you are playing open chords, rather than barre chords – this turnaround makes a great choice. For this reason, I would recommend it if you are playing acoustic or country style blues.

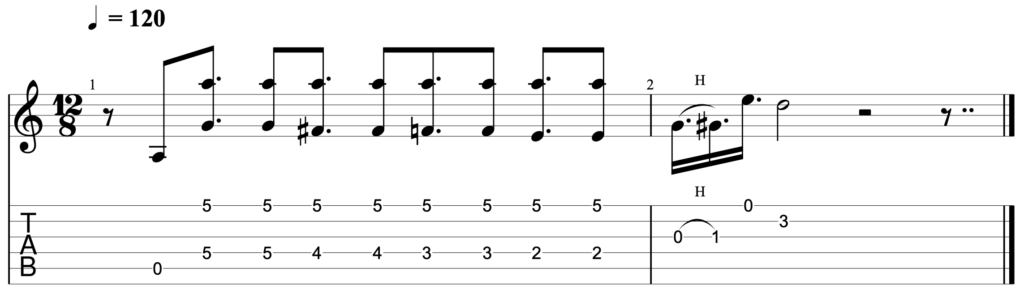

4.) Hybrid picking turnarounds

This next example is quite similar to the single note line illustrated above. The key difference however, is that here the turnaround utilises a hybrid picking idea. This is what this turnaround looks like:

And at 120 BPM, this is what it sounds like:

Instead of just moving across a single string – as shown above – here you play the same idea, but across multiple strings.

This might seem like a small change. But it adds a lot more life to the turnaround, particularly if you are playing unaccompanied. As such, it works very well if you are playing acoustic or Delta style blues.

If you are new to hybrid picking, it can be quite a challenging technique at first. But stick with it, as it is a technique that is used a lot in blues turnarounds, and which will appear in a further number of the examples below.

5.) Pedal tone turnarounds

This turnaround idea is inspired by that which Robben Ford uses in his instrumental ‘Cannonball Shuffle‘. This is what this turnaround looks like:

And at 120 BPM, this is what it sounds like:

At first, it may appear almost identical to the hybrid picking idea demonstrated above. The difference however, is that here, the notes on the strings do not descend simultaneously. Instead, the note on the high E string is played repeatedly, and the notes on the D string descend.

In this example, the note that is sustained appears at the 5th fret on the E string. This is the note of A – which is the root note in the key of A. This creates an interesting effect. The root note is repeated – providing a sense of stability – yet at the same time, a descending chromatic run is played along the D string.

This idea – of playing one note repeatedly whilst you simultaneously play additional notes – is called pedal point, or pedal tone technique. The repeating notes are often played on the bass strings, whilst guitarists simultaneously play melodies on their treble strings.

And in fact, a lot of Delta blues guitarists utilised this technique. This is because it helped them to create a rhythmic bass part, even when they were playing unaccompanied.

As shown above though, you don’t have to repeat notes on your bass strings. The idea also works very effectively in a lead guitar or soloing context too.

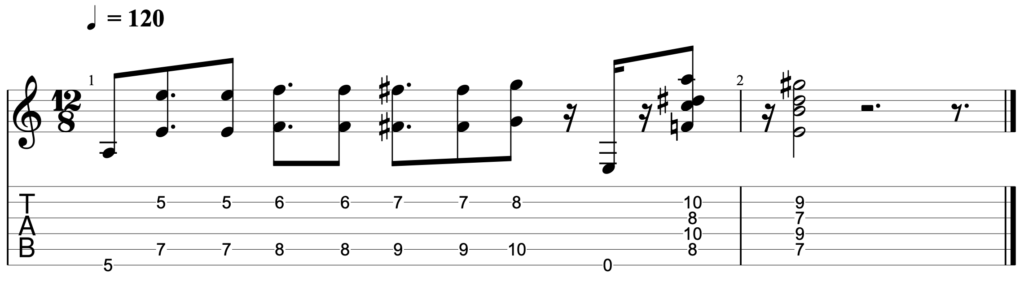

6.) Ascending turnarounds

In the same way that chordal blues turnarounds use both ascending and descending chromatic ideas, the same is true of turnarounds played on single strings. Here then we see a simple ascending idea that connects the chords of A7 and E7. This is what this turnaround looks like:

And at 120 BPM, this is what it sounds like:

In contrast to the blues turnarounds in the previous example, this is played in a different section of the fretboard. This shows that it is possible to take the ideas from the earlier examples, and play them in other parts of the neck. In this way, you can get more mileage from a handful of simple ideas.

7.) Mix & matching turnarounds

Although it might seem obvious, I think it is worth noting that you can take different ideas from the blues turnarounds listed above and combine them. In this example, a chromatic ascending line is combined with hybrid picking, before the turnaround finishes by connecting two chords chromatically.

This is what this turnaround looks like:

And at 120 BPM, this is what it sounds like:

Although this turnaround does make use of some chromatic chord movement in the second bar, it is predominantly based around single notes.

However you can take the idea of combining elements from multiple blues turnarounds and base them around chords, rather than single notes. You can see this in the following example:

This is what this turnaround sounds like at 100 BPM:

This turnaround is inspired by the rhythm guitar part in the song ‘Strange Brew‘, by Cream. In this song, Eric Clapton combines chords with hammer ons and single note lines. And this gives the progression a more lively, rock feel.

So if you want to make your blues turnaround (or even your whole 12 bar blues progression) more interesting, experiment with this idea. In this way, you can still play chords and support the rhythm section, whilst playing a more varied guitar part.

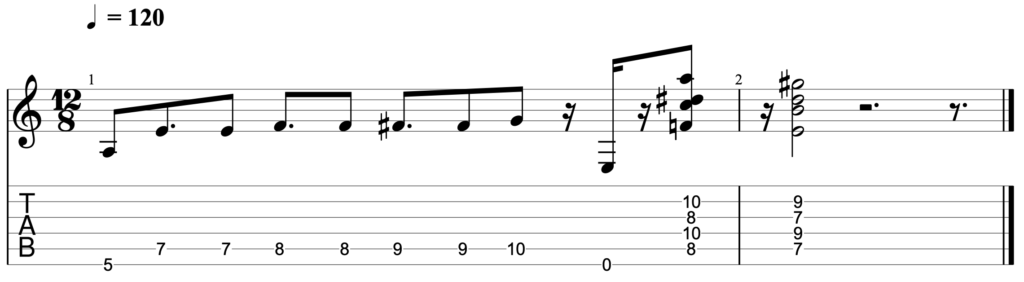

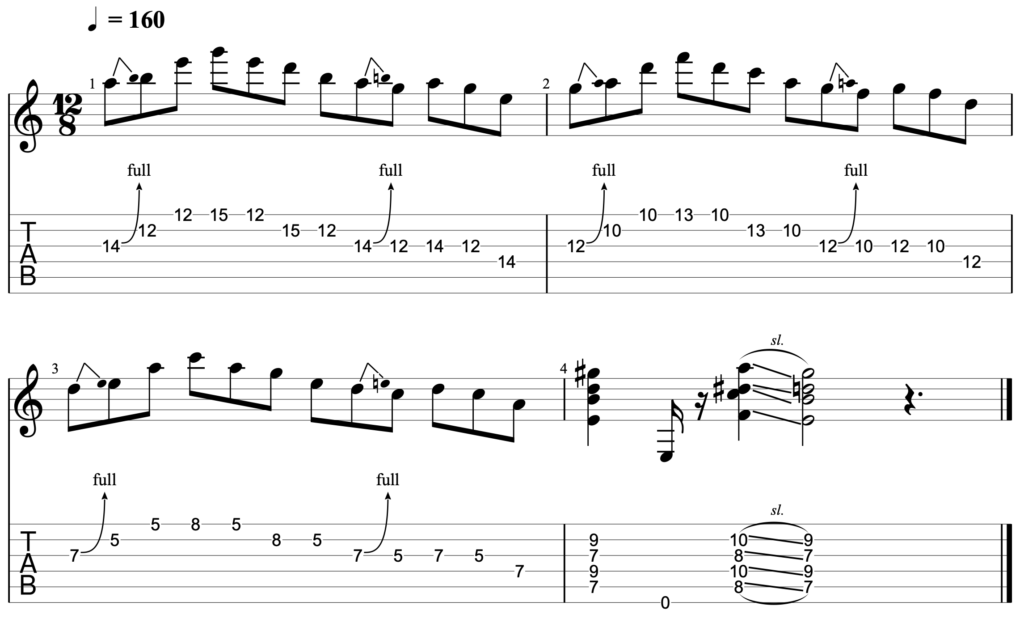

8.) Contrapuntal turnarounds

We can take some of the hybrid picking ideas illustrated above and create one further variation by utilising what is known as ‘contrapuntal movement’.

This is a term which describes two separate melodies which are played at the same time, and which move in opposite directions. I appreciate this sounds complicated. But it becomes much easier to understand when you look at the example below. This is what this turnaround looks like:

And at 120 BPM, this is what it sounds like:

As you can see, the notes on the B string are descending. They move from the 8th fret, down to the 5th fret. On the A string, the opposite is true. The notes on this string are ascending. They move from the 4th fret, up to the 7th fret. This creates an interesting and unusual sound, as the two different melodies converge.

This movement can feel awkward when you first get started. But keep working on it, as you can use this contrapuntal idea to create effective blues turnarounds in different keys and in different sections of your fretboard.

9.) SRV style turnarounds

This is a more radical example of how you can approach blues turnarounds when playing lead guitar. Here the turnaround idea is extended over 4 bars, and follows the typical 12 bar blues progression – playing the V, IV and I chord, before moving back to the V chord. This is what this turnaround looks like:

And at a lively 160 BPM, this is what it sounds like:

Unlike the majority of the blues turnarounds listed here, this turnaround does not make use of chromaticism. Instead it focuses on a series of single note licks that are based around the minor pentatonic scale.

Specifically, each bar is based around a minor pentatonic scale shape which corresponds to the chord that appears in that part of the 12 bar blues progression.

In the first bar for example, the lick is based around the first shape of the E minor pentatonic scale. It then shifts to focus on the first shape of the D minor pentatonic scale in the second bar, and then the first shape of the A minor pentatonic scale in the third bar.

In other words, it follows the chord progression from the chord of E7 (V chord), to D7 (IV chord) to the A7 (I chord.). In the final bar, the pentatonic licks stop, and the phrase resolves with a slide into the E7 chord.

This turnaround is very much in the style of Stevie Ray Vaughan, and is similar to that which appears at the beginning of his song ‘Honey Bee‘. As such, you can use this turnaround very effectively as an introduction.

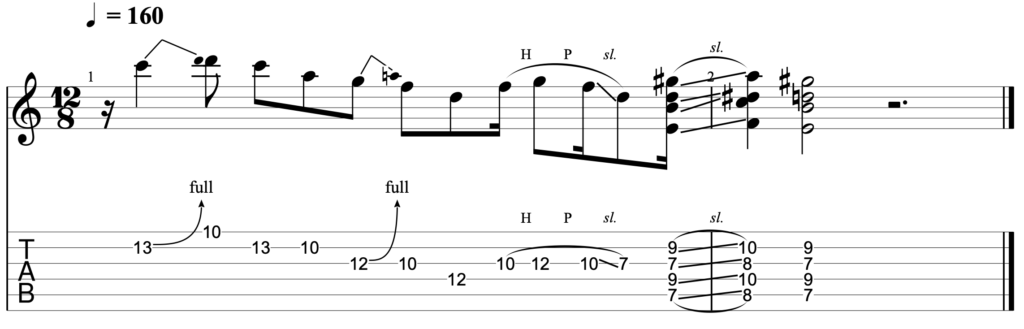

10.) Lead guitar turnarounds

This final idea is similar in its approach to the previous example. In other words, it is best suited if you are a lead guitar player and want to add a lick to spice up the final couple of bars of the 12 bar blues progression. This is what this turnaround looks like:

And at 160 BPM, this is what it sounds like:

In contrast to the lick above however, this turnaround lasts for just 2, rather than 4 bars. This makes it appropriate to use in a number of different circumstances.

The first of these is if you are the only guitarist playing in your band. You might not feel comfortable shifting away from playing chords for a whole 4 bars. In this way you can breath life into the turnaround, whilst still supporting the rhythm section through the majority of the 12 bar progression.

The second and quite different scenario – is if you are playing in a band with either multiple different guitarists or a keyboard player. With so many musicians playing and so much density in the rhythm part, it might not be appropriate to add to that by playing what is essentially a 4 bar solo over the top.

By taking the approach shown above, you can spice up the blues turnaround, without clashing with your bandmates.

Regardless of the circumstance in which you choose to use this idea though, I think it is one of the most effective of those listed here.

It is less obviously based around the pentatonic scale shapes that correspond with the chords in the 12 bars blues. And in my opinion this makes it sound more interesting and sophisticated.

Using blues turnarounds in practice

The above list of blues turnarounds is not exhaustive. There are innumerable ways that you can bring life and variety to your blues turnarounds. In addition to all of the ideas above, you can also:

- Use different chords

- Play different voicings of the chords you normally use

- Manipulate the rhythm of the turnaround

As you can see from the examples above – chordal and riff based turnaround ideas typically use chromaticism and simple ascending and descending lines to connect the chords used in the final 4 bars of a 12 bars blues.

Conversely, lead guitar based turnarounds often target pentatonic scale shapes that correspond with the chords of the 12 bar blues.

These are sweeping generalisations. And of course there are many different types of blues turnarounds. However, if you are just getting started with blues turnarounds, then keep these basic principles in mind.

Combine them with the examples listed above, and you will soon be on your way to developing a range of your own killer blues turnarounds.

Good luck! And if there is anything at all I can help with, or if you have any questions, just pop them in the comments below or send me an email on aidan@happybluesman.com and I’m happy to help!

References & Images

Pixabay, YouTube, Wikipedia, Justin Guitar, Blues Guitar Institute, The Guitar Head, Guitar Player, Premier Guitar, Best Blues Guitar Lessons, Guitar, Riff Journal

Responses

This is very useful, Aidan, particularly with tabs and how it would sound at the end of each section

Thank you so much for the kind comment my man, and I am so happy to hear you found the article helpful 😁