A couple of weeks ago, I wrote an introduction to the 12 bar blues.

This is the most commonly occurring chord progression in the blues, and one you need to get under your fingers if you want to progress as a blues guitarist.

Once you know that chord progression back to front and across a variety of different keys, you can think about adding an additional layer of complexity.

The first way to do this is to use what are known as dominant 7th chords.

Dominant 7th chords in the blues

Dominant 7th chords are the most commonly used chords within the blues.

In my previous article, I wrote that the 12 bar blues progression was built upon the I, IV and V chords.

Whilst this is true, it is overly simplistic. Blues musicians very rarely play the straight versions of the I, IV and V chords in a 12 bar blues progression.

This is because broadly speaking, chords that are major sound happy, and those that are minor sound sad. The blues is not always sad music, and it can of course be uplifting.

However there is a certain tension within the blues which is integral to the sound and feel of the genre.

If you want to test this out, play a 12 bar blues using straight major chords. You will hear that there is something missing.

It just won’t sound like blues music – and this is just because it is difficult to create a bluesy feeling using straight major chords.

As a result of this, blues music tends to be built around what are known as dominant 7th chords.

Intervals and chord theory

Before we get into the specifics around dominant 7th chords and their place in the blues, it is worth briefly revisiting some of the theory outlined in my last article.

Western music is based around keys which are built around scales. The major scale is one of the most commonly used scales and so will provide us with our examples here.

In the key of C for example, the notes of the major scale are as follows:

C D E F G A B

C is the first note of the scale, D is the second and E is the third etc.

These notes have corresponding chords that are marked using Roman numerals. So if you were playing a 12 bar blues – C would be the I chord, F would be the IV chord and G would be the V chord.

Each of these chords is built from notes within the scale, and this is where intervals come in.

Distances between notes in a scale are measured using intervals.

If you have heard terms like ‘minor third’ or ‘perfect fifth’, you will have come across intervals before.

There are 5 different types of interval, which are as follows:

- Perfect

- Major

- Minor

- Augmented

- Diminished

Each of these intervals has a different sound and characteristic, and the intervals between the different notes used within a chord define the characteristic of that chord.

Major vs. dominant 7th chords

I won’t delve too much deeper into the theory at this stage.

However it is worth really understanding the idea that each interval has a characteristic sound, and how you ‘stack’ those intervals within a chord will define the sound of that chord.

Major chords are built using ‘perfect’ and ‘major’ intervals.

In a major triad (a chord made of 3 notes) the notes used are the root note, major third and perfect fifth. There is no dissonance between these intervals, and so the chord sounds happy and upbeat.

A dominant 7th chord contains all of these notes. Crucially though, it also contains the addition of an extra note – the minor 7th.

This totally changes the sound of the chord. The minor 7th is a semitone lower than the major 7th, which is the interval that you find in a major 7th chord.

This creates dissonance within the chord, and gives it a tense and unresolved sound. It is also what makes dominant 7th chords perfect for the blues.

Applying dominant 7th chords to the 12 bar blues

To add a bluesy feel to your 12 bar blues structure, you need to play the I, IV and V chords as dominant 7th chords.

The good news here, is that by learning just 2 chord shapes, you can play the 12 bar blues using dominant 7th chords, in a whole range of different keys.

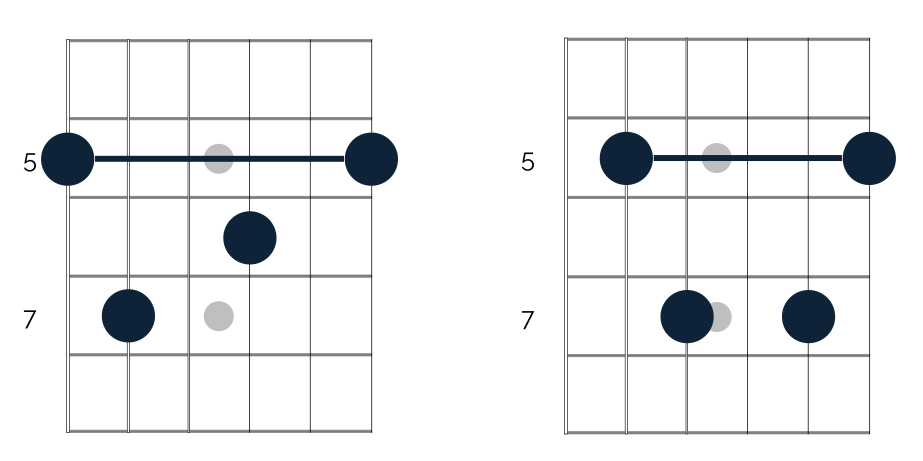

All you need to know are these 2 barre chord shapes:

Shape 1 is what you will use to play the I chord in the 12 bar blues progression. The specific chord shown above is A7.

Shape 2 is what you will use to play the IV and V chords in the 12 bar blues progression. The specific chord shown above is D7.

In this specific example, the the 2 chords above represent the I and IV chords in the key of A. This is a nice place to start to learn the chord shapes, as A is one of the most commonly used keys in the blues.

Once you have those 2 shapes underneath your fingers, you can easily move them around the neck to form the I, IV and V chords in a variety of different keys.

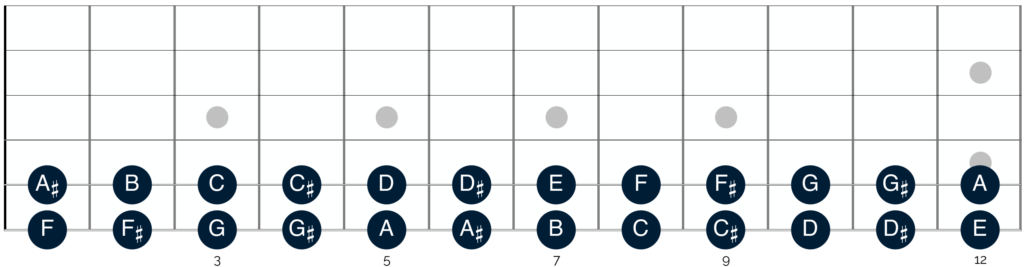

To achieve this, you just need to learn the notes on the 6th and 5th string of your guitar, as shown below:

Once you know those notes, applying dominant 7th chords to the 12 bar blues is a nice and easy. This is how you do it:

The I chord

To play the I chord, all you have to do is take Shape 1, and then pick the root note on the 6th string from the key you are in.

As an example, if you are playing a 12 bar blues in G, take shape 1, and start by placing your first finger on G on the 6th string. Create the shape 1 chord from there.

If you are playing a 12 bar blues in A, take the same shape and slide it up 2 frets. You then you have your I chord in the key of A.

The IV chord

For the IV chord, you can apply the same idea. All you need to do is take shape 2, pick the corresponding note you are searching for on your 5th string, and play the chord from there.

So in the key of A, you know the IV chord is D. All you need to do is find D on the 5th string. Place your first finger on D and then apply shape 2.

In the key of B, you know the IV chord is E. So again you just need to pick out E on the 5th string and apply the same chord shape.

The V chord

Picking out the V chord is even easier. In any key, all you need to do is take shape 2, and slide it up 2 frets from the IV chord.

So in A, you know that E is the V chord. All you have to do is find D (the IV chord), move the shape up 2 frets and you have the V chord. In even better news, you can apply this idea to any key!

Putting it all together

To get to grips with this idea, pick a key (A is always a good starting place) and move through shapes I, IV and V using the dominant 7th chords.

Once you can do this in the key of A, switch keys and try it in G, B and D etc.

Do this and you should notice 2 things:

Firstly, using dominant 7th chords sounds a lot better and much bluesier than using straight major chords.

Secondly, when you use these 2 shapes, you can play the whole 12 bar blues progression very neatly in a box shape, using only a small portion of your neck.

Playing the 12 bar blues in this way will really unlock the neck for you and give you all of the tools to play authentic blues rhythm in a variety of different keys. It will also allow you to do this without thinking too much.

Once you know the chord shapes and the notes on your 6th and 5th strings, you are totally set up and don’t need to get too bogged down in complex music theory.

The next steps

When getting to grips with those chord shapes, you may have noticed one more thing; they sound better in some keys than others.

Broadly speaking, they work really well on those keys where the tonic notes appear in the middle of the neck – like G, A and B.

Once you get up to D and E, you move to quite a high register on the neck, and the chord shapes I’ve suggested lose a bit of that dark and moody sound which is so authentically bluesy.

The next step in developing your rhythm playing then, is to learn alternative chord ‘voicings’.

These will add extra variety to your playing, and will help you move around the neck and play in different keys with greater ease.

I will cover those in much more detail in a future article.

For now though, get to grips with using dominant 7th chords and the shapes I’ve outlined above. You’ll be amazed at how they transform your rhythm playing.

Good luck, and if you have any questions, just post them in the comments below!

References

Youtube, Wikipedia, My Music Theory, Ear Master

Responses

I think you made a mistake in “The minor 7th is a semitone lower than the the octave.” – the MAJOR 7th is. A minor 7th would be 2 semitones, or a whole step lower than the octave, no?

Right you are Matt and thanks very much for spotting the mistake! I meant to write ‘This totally changes the sound of the chord. The minor 7th is a semitone lower than the major 7th, which is the interval that you find in a major 7th chord.’ I’ve just changed that above now. Thanks again! 😁