If you want to create effective blues guitar solos, I would strongly recommend learning the blues scale.

As the name suggests, this is a scale that creates a distinctly ‘bluesy’ sound. And as such – it has been used to great effect by countless blues and blues rock guitarists. In fact, for many guitarists, the blues scale is the first scale that they learn after getting to grips with the minor pentatonic scale.

If you are fairly new to the world of blues lead guitar and you haven’t yet encountered the minor pentatonic scale, I would recommend starting with my article: ‘A Beginner’s Guide To The Minor Pentatonic Scale‘.

That will set you up with a lot of the information you need to start soloing and improvising in a blues context.

If however you feel comfortable playing the minor pentatonic scale, and you are now looking to add some variety to your lead playing, then getting to grips with the blues scale is one of the best places to start.

In this article I outline everything you need to know about the blues scale. I cover:

- The key differences between the blues scale and the major and minor pentatonic scales

- How you can effectively use both the minor and major version of the blues scale

- Different ways that you can mix the major and minor blues scales to add variety and depth to your playing

- Examples of famous songs that utilise the blues scale

So without further ado, here is everything that you need to know about the blues scale:

Some scale theory

Before we dive in and start looking at how to play the blues scale, it is first worth covering the basics of how the scale is constructed. Don’t worry – I won’t get too deep into music theory here; I will just cover the essentials. This will help to give you a greater understanding of what you are actually playing. And this is important.

To understand how the blues scale is created, we need to first look at the major scale. This provides us with the basis of Western music. All other scales are spoken about in relation to this scale.

The major scale is a ‘heptatonic scale’. This is because it is comprised of 7 notes per octave (hepta meaning 7). The scale ‘formula’ of the major scale is as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Each of the numbers above describes a note from within the major scale. 1 is the first note of the scale, 2 is the second note, and so on. In the key of A, the notes of the major scale are as follows:

A B C♯ D E F♯ G♯

So each of the numbers 1-7 corresponds to one of the notes above. A is 1, B is 2 and so on. This scale formula is always used as the reference point when talking about other scales.

Let’s look at the minor scale for example. The scale formula for the minor scale is as follows:

1 2 b3 4 5 b6 b7

In the key of A, this changes the notes of the scale. The 3rd, 5th and 6th notes have all been flattened. And this reduces their pitch by a semi-tone. So the notes of the minor scale in the key of A are as follows:

A B C D E F G

The 3 notes mentioned above have all been flattened by a semi-tone. So the sharps that were present in the A major scale do not appear here.

Pentatonic scale construction

Although the major scale provides the foundation of most Western music, it is very rarely used in the form noted above. This is because put simply, the major scale lacks some of the edge and tension that we like to hear when we listen to popular forms of music.

Instead, scales that are derived from the major scale – as well as the minor scale – appear with greater frequency. Both the major and minor pentatonic scales are examples of this.

A pentatonic scale is one that is made up of only 5 notes per octave (penta meaning 5).

There are two types of pentatonic scale; the major and the minor pentatonic scale. Both of these are important, and both are widely used in blues and rock guitar playing. This is especially true of the minor pentatonic scale, which has come to define the sound of blues and rock music.

The minor pentatonic scale is derived from the minor scale and has the following scale formula:

1 b3 4 5 b7

As you can hopefully see, it contains notes from the minor scale, but it contains 5, rather than 7 notes.

Similarly, the major pentatonic scale is derived from the major scale and has the following scale formula:

1 2 3 5 6

So it contains notes from the major scale, but again it only contains 5, rather than 7 notes.

What is the blues scale?

At this stage, you might be wondering why I am talking about pentatonic scales, rather than the blues scale.

In short, this is because the easiest way to understand the blues scale is to view it as a pentatonic scale, with the addition of 1 extra note. This makes the blues scale a ‘hexatonic’ scale, as it contains 6 notes per octave, with ‘hexa’ originally meaning 6.

There is a minor version of the blues scale, which is almost identical to the minor pentatonic scale. It just has the addition of one extra note.

There is also a major version of the blues scale. Similarly, this is almost identical to the major pentatonic scale, but with the addition of one extra note.

The additional note that appears in the scale is often referred to as the ‘blue note’. This is a chromatic note, which changes the sound of both of the standard pentatonic scales and makes them both harmonically richer.

It also allows you to create sounds and a feel in your playing that is difficult to do when you just stick to the notes in the pentatonic scales.

So, if you are looking to add some further depth and variety to your lead guitar playing, learning the minor and major blues scales is a brilliant place to start.

And the great news here is that the shapes of the blues scale are almost identical to those of the pentatonic scales. Let’s look at this in more detail, in both a minor and major context:

The minor blues scale

For reasons that I will cover in more detail below, the minor version of the blues scale is likely to be the one that you use more frequently.

As mentioned earlier, the only difference between the minor pentatonic scale and the blues scale is that the latter features one extra note. In the minor blues scale, this note is the b5 (flat fifth) – also commonly referred to as the blue note. All of the other notes of the scale remain the same.

The construction of the minor pentatonic scale is as follows:

1 b3 4 5 b7

Whereas the structure of the minor blues scale is as follows:

1 b3 4 b5 5 b7

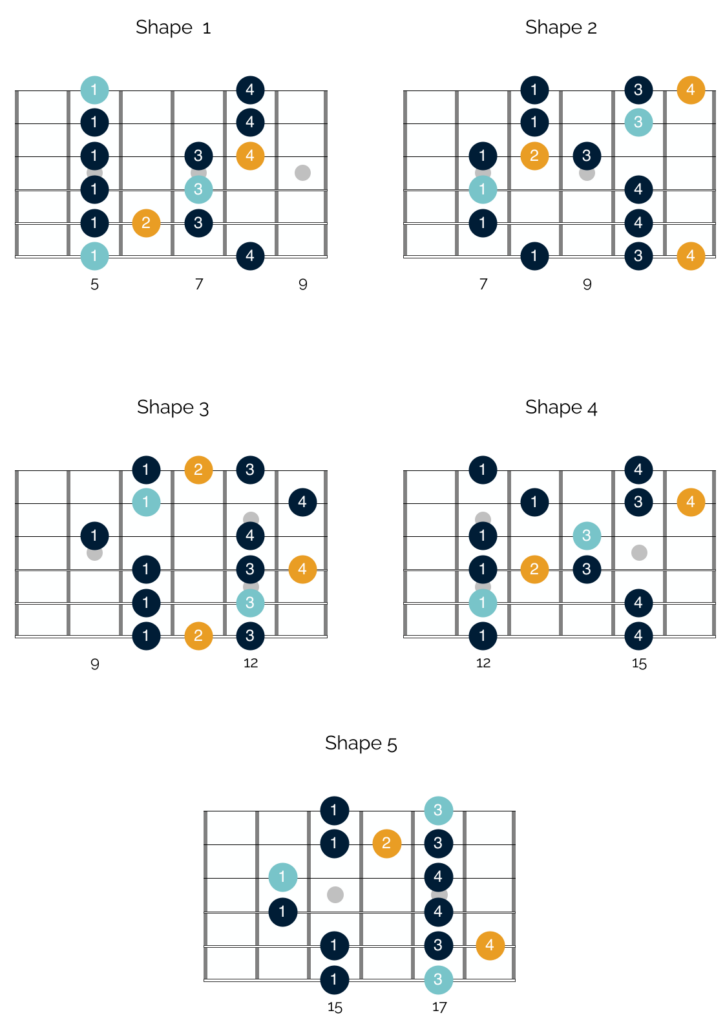

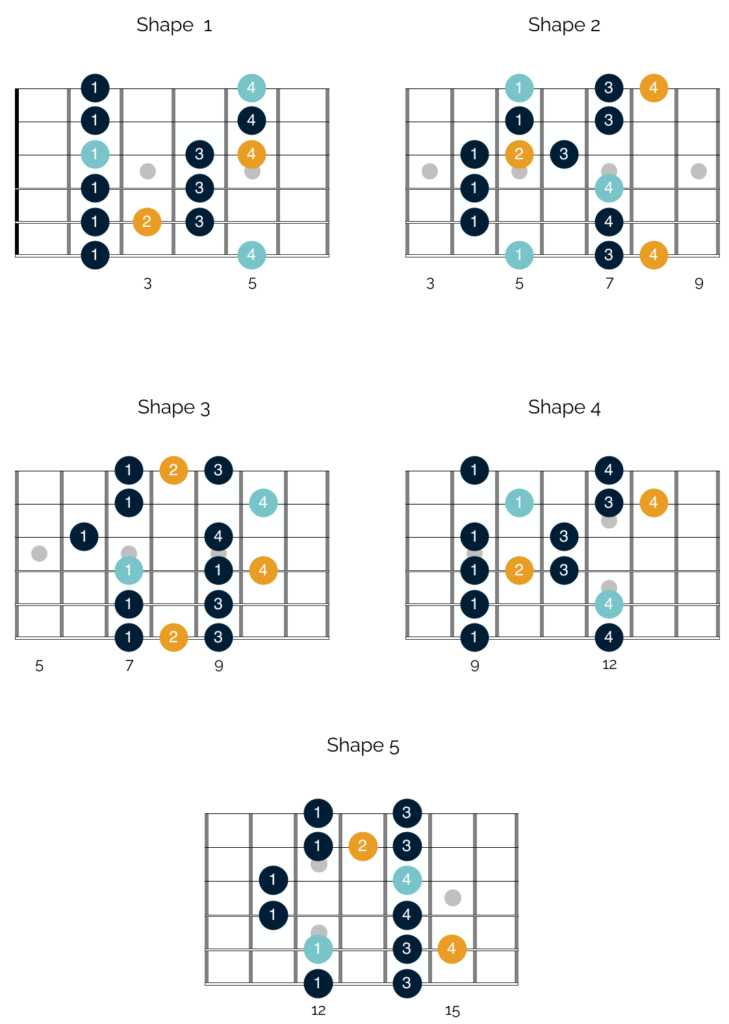

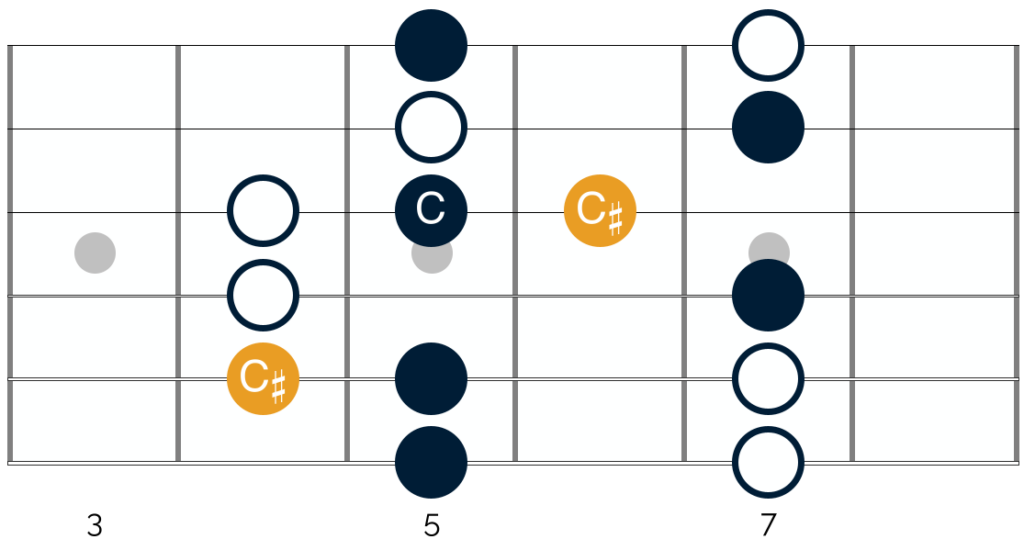

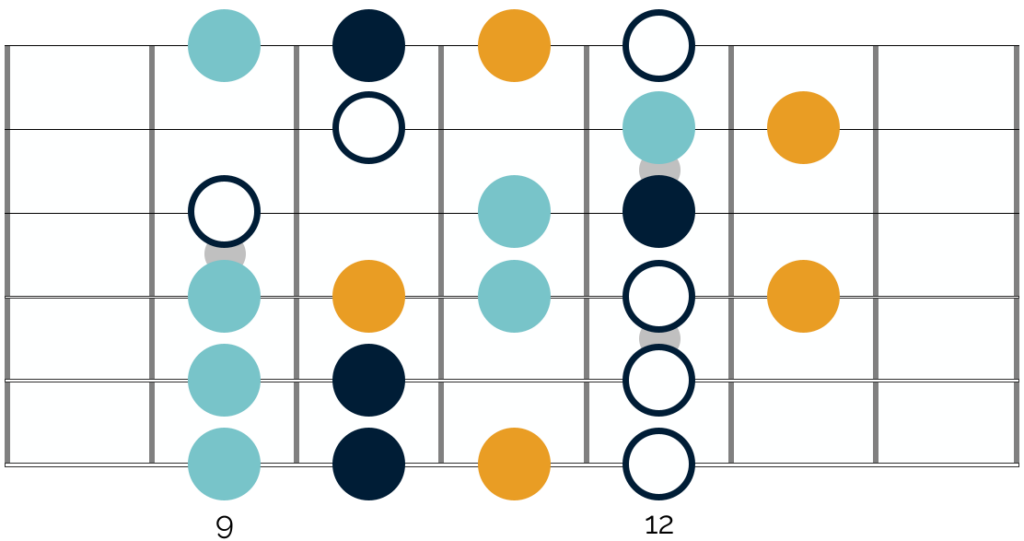

Looking at the scale formulae in this way, it is somewhat challenging to understand how to apply the blues scale to your playing. But this all changes when you see the shapes of the minor blues scale. Here they are in the key of A minor:

The diagram here shows the shapes of the minor blues scale. The notes in green are the root and octave notes (in this example they are the notes of A), and the notes in blue are the new notes from the blues scale.

As you can hopefully see, the shapes of this scale are almost identical to those of the minor pentatonic scale. The only difference is the addition of the ‘blue note’.

How to use the minor blues scale

As noted above, the easiest way to understand and view the blues scale, is as a pentatonic scale with the addition of one extra note. So, if you want to use the scale in your soloing, all you need to do is play it in those situations where you currently use the minor pentatonic scale.

If you are new to this material, or if you need a little refresher on what those situations are, they are as follows:

When playing in a minor key

The first playing situation in which you can use the minor pentatonic or minor blues scale is nice and straight forward. If you are playing a song in a minor key, you can solo using the corresponding minor pentatonic or minor blues scale.

As an example, if you are playing a song in B minor, you can solo and improvise using the B minor pentatonic or B minor blues scale. If you are playing in the key of G minor, you can solo and improvise using the G minor pentatonic scale or G minor blues scale, and so on.

When Playing Blues In A Major Key

Within a blues or blues rock context, you can also solo using the minor pentatonic scale or minor blues scale over a major chord progression.

From a theoretical point of view, this doesn’t make sense. This is because the minor third that you find in the minor pentatonic and minor blues scales clashes with the major third that you find in the chords in a major progression.

This creates dissonance, which is why traditional music theory advises against mixing minor and major tonalities in this way. Certain genres though – the blues being one of the most notable – have long been breaking the rules.

As I outlined in more detail here, blues songs are usually built around a 12 bar chord progression. This chord progression is typically comprised of dominant 7th chords. These chords are unusual, in that they blend the minor with the major. Specifically they contain the root note, a major third, perfect fifth, and a minor seventh.

This minor seventh clashes with the rest of the chord, creating a somewhat tense and unresolved sound. This sound is not harsh on the ears, and in fact it creates a feeling that we now associate with the blues.

When you solo over a chord progression built from these chords, the minor pentatonic scale or minor blues scale both make a great choice. There is already a major/minor clash contained within the chords, and so the dissonance that you would normally create by playing the minor pentatonic over a major chord progression is diminished.

As above, you can play the minor pentatonic or minor blues scales over all of the chords in a major 12 bar blues progression and they will both sound brilliant.

What about the blue note?

It is worth pointing out here that whilst the minor blues scale and minor pentatonic are interchangeable, they are not identical.

And whilst there may be only one note separating the two scales, the difference that this single note makes is significant. This is because it introduces an element of chromaticism and tension into your playing.

This element of tension is not really present when you just play using the minor pentatonic scale.

In fact part of what makes the minor pentatonic such a popular scale amongst blues guitarists (and guitarists more generally) is that you can play it in a wide range of different contexts, without hitting any notes that create a lot of tension or dissonance.

Just listen to this clip:

Here the first shape of the A minor pentatonic scale is played over an A minor chord. And as you can hopefully hear, there is no sound of dissonance or tension whatsoever. The same is true if you hold or repeat any of the notes within the minor pentatonic scale.

Although some of those notes work more effectively as notes to hold or repeat, you won’t find any that create a very harsh dissonance.

The same is also true over 12 bar blues progressions and in most (if not all) contexts where you are able to play the minor pentatonic scale. Of course, there are notes that sound more harmonious over different chords. But when using the minor pentatonic, you are never at great risk of hitting a note that really makes you wince.

The same is not true for the minor blues scale. Now listen to this clip:

Here, the blue note at the 8th fret of the G string (in the first shape of the A minor blues scale) is played over the A minor chord. And as you can hopefully hear, this creates a harsh dissonance that is really quite unpleasant.

Replacing the minor pentatonic with the minor blues scale

Given that the blue note creates a harsh and dissonant sound, you may be asking why you would even want to use the blues scale.

In short, it is precisely because the scale creates this dissonant sound, that you should include it in your playing.

To be an effective blues guitarist, you need to be able to make your listeners feel emotion. And one of the best ways to create emotion is to manipulate tension. You want to be able to build a sense of tension, before releasing it at the right moment.

There are many different ways to create and resolve tension. But including chromatic notes – like the blue note – in your playing is one very effective way to manipulate tension.

Striking the balance

As mentioned above, you can use the minor blues scale and minor pentatonic scales interchangeably. The only key difference is that when you play the blues scale, you also have to consider how to effectively utilise the blue note.

The key to success here, is to use the blue not sparingly. You do not want to stick around on this note and let it ring out. Otherwise you will end up with the harsh and grating sound you can hear on the audio clip above.

Instead, you want to treat the additional note of the minor blues scale as a ‘passing note’.

In other words, use the blue note to travel between all of the other notes in the minor pentatonic scale. In this way you will create a sense of tension in your playing, but it will only be momentary.

The sense of tension will resolve when you pass over the note and return to one of the notes found in the minor pentatonic scale.

This added element of chromaticism sounds amazing when you use it correctly. It adds a depth and variety to your lead guitar playing and makes it sound more sophisticated.

The key pitfall that you need to be wary of, is to not overuse the additional note of the blues scale. This note adds a bit of spice and variety to your solos.

But in the same way that too much spice can overwhelm an otherwise perfectly cooked dish, the same is true here. Especially when you are just getting to grips with the blues scale, take a conservative approach. Less really is more in this context.

The minor pentatonic vs. the minor blues scale

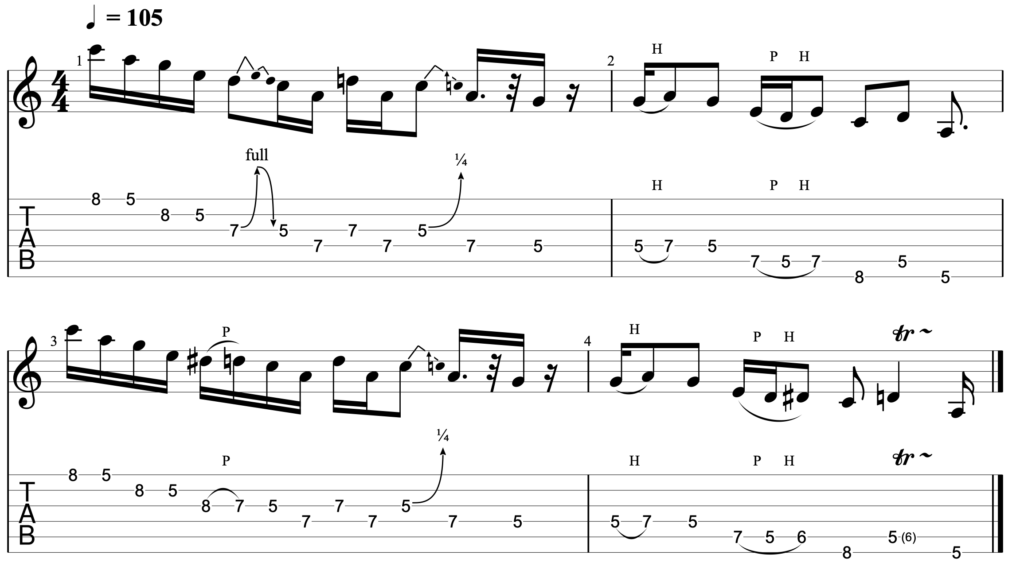

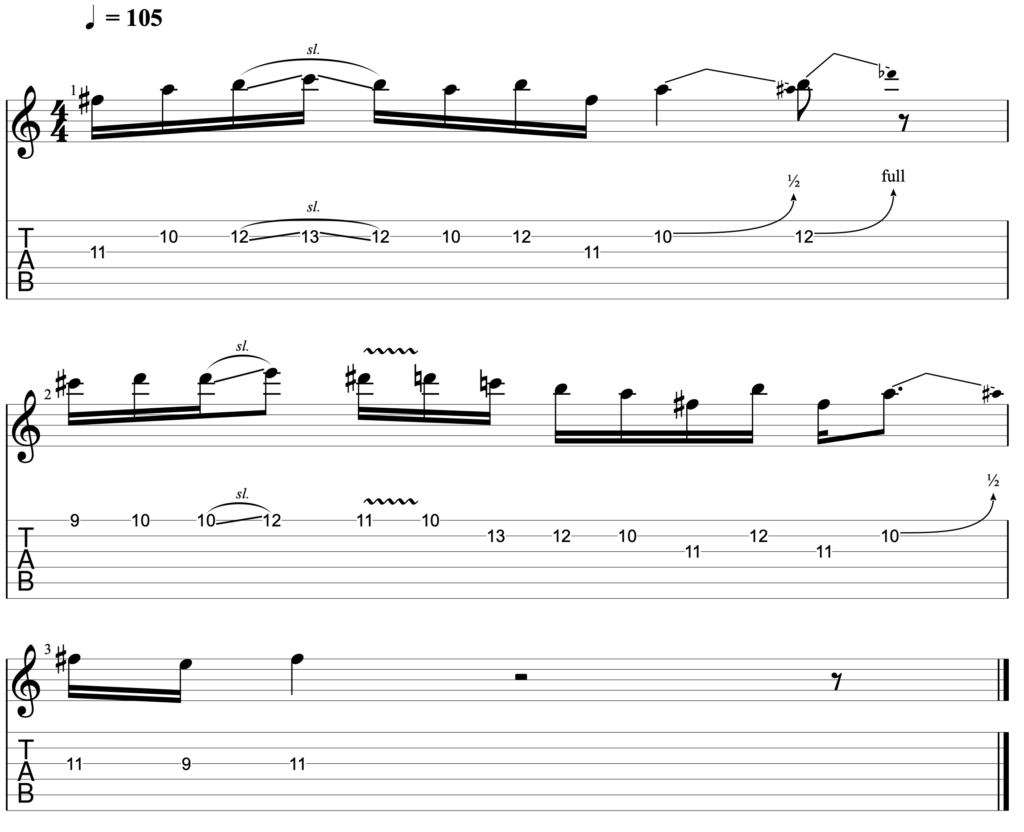

To help give you a better idea of how to use the minor blues scale effectively, here are 3 different licks that show how to use it in practice. In each of these examples, the first bar is a lick based around the minor pentatonic scale. The second bar is a similar lick, but with the addition of the blue note from the blues scale.

On the audio there is a bar of rest in between the licks. This is not shown on the tab, but it gives a bit of space between the 2 different licks, which will help you to compare them more easily. All of these licks are in the key of A minor.

Lick 1

At 105 BPM, this is what these 2 licks sounds like:

In this first lick, we start with a descending run based on shape 1 of the minor pentatonic scale. In the second variation however, we add in the blue note. This happens first during the descending run, and then more obviously with the trill at the end of the lick.

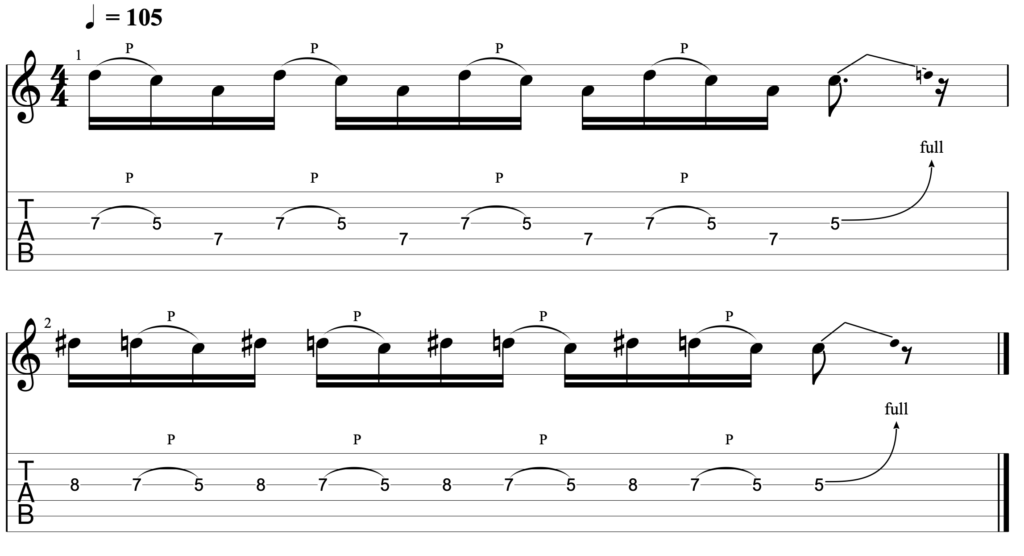

Lick 2

At 105 BPM, this is what these 2 licks sounds like:

In this simple lick, the use of the blue note is more obvious. This is a great example of how you can use it in your playing to build tension. The tension builds as the pattern repeats, before it resolves with the bend at the end of lick.

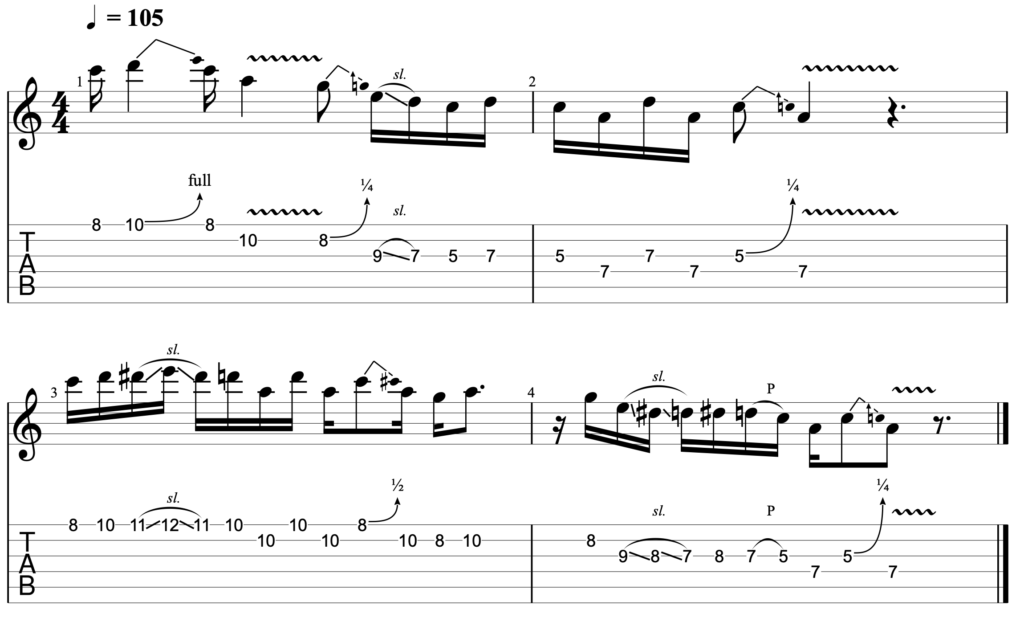

Lick 3

At 105 BPM, this is what these 2 licks sounds like:

This final lick shows how you can use the blue note to move between different positions on the fretboard. Here the use of the blue note is more deliberate and obvious, illustrating the type of feel you can create when you include it in your playing.

In isolation – and perhaps apart from the final lick – none of the licks utilising the blue note sound wildly different from the minor pentatonic lick. But if you construct an entire solo using the blues scale and make repeated use of the blue note, you will be amazed at how different your lead playing starts to sound.

The minor blues scale – a recap

At this point, I think it is worth pausing for a moment. We have already covered a lot of material, and it’s important to take these ideas one at a time. So before you move on, I would recommend spending some time really focusing on how to use the minor blues scale in your playing.

It is much better to take a little longer learning the minor blues scale – but to properly understand it – than it is to rush in and fail to learn how to use it effectively.

When I first learnt this scale, I solely focused on it for about 2 weeks. These were the steps I took to really grasp the shapes of the scale and how to use it in the right context:

- To start with, I played the scale shapes up and down the neck, in each of the different positions in A minor. I played the scale shapes along to a metronome, as described in exercise 1 above.

- Once I had a solid grasp of the scales and positions of the A minor blues scale, I put on an A minor blues backing track.

- At first, I started by playing the shapes of the A minor blues scale over the backing track. I moved up and down the neck, between each of the different positions.

- Once I had that nailed, I started improvising over the backing track using the A minor blues scale. I had two aims here. The first was to ‘meander’ across the fretboard and move between each of the different positions as much as possible. This helped me to get familiar with the different shapes of the scale across the neck.

- The second was to experiment with the blue note. I tried to adjust all of my ‘go-to’ licks and phrases to include the blue note. This helped me to understand the differences between the minor blues scale and the minor pentatonic scale. It also gave me an understanding of how to use the blue note effectively, without my playing becoming saturated with it.

- After I felt comfortable soloing in A minor, I repeated the process in B minor and C minor etc. I did this until I was familiar with the different positions of the minor blues scale in these alternate keys.

The major blues scale

Once you have gone through the above process and you feel truly comfortable using the minor blues scale, you can turn your attention to the major blues scale.

This is provided that you know the shapes of the major pentatonic scale and you also understand how to use it.

If that is not the case, then I would first recommend reading my article: ‘A Beginner’s Guide To The Major Pentatonic Scale‘. In that article I outline everything you need to know about the major pentatonic scale, its shapes, and how to apply it in your playing.

It is important to have this knowledge first. For in the same way that the minor pentatonic and minor blues scales are almost identical – both in terms of their construction and application – the major blues scale is very closely related to the major pentatonic scale.

We can see this initially by looking at the construction of the scale. The only difference between the major blues scale and the major pentatonic is that the former features one extra note.

In the major blues scale, this note is the b3 (flat third) – also commonly referred to as the blue note. All of the other notes of the scale remain the same.

The construction of the major pentatonic scale is as follows:

1 2 3 5 6

Whereas the structure of the major blues scale is as follows:

1 2 b3 3 5 6

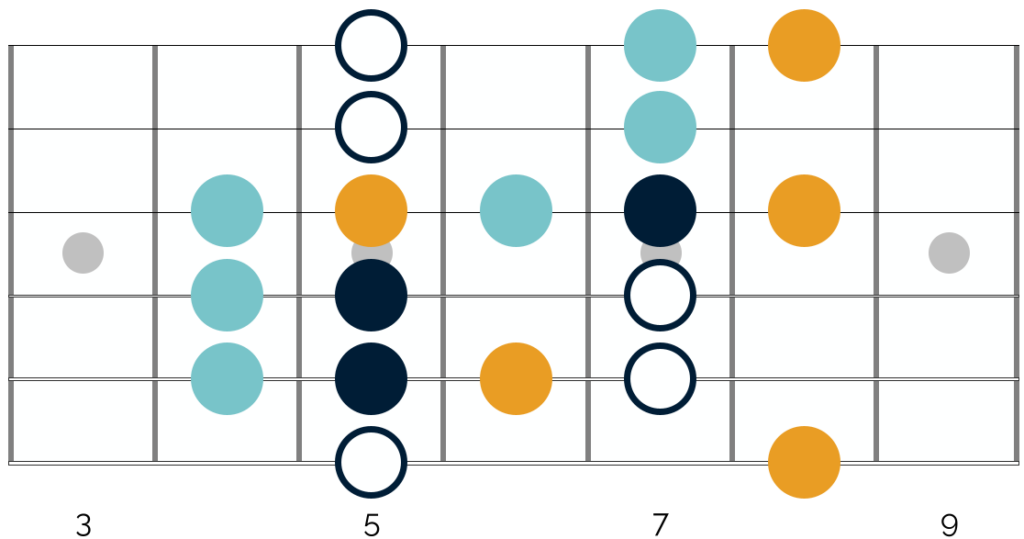

And again, to bring this idea to life a bit more, this is what the shapes of the major pentatonic scale look like when they are laid out on the fretboard:

The notes shown in green are the root and octave notes (in this example they are the notes of A). The notes in blue are the new notes from the blues scale.

As you can hopefully see, the shapes and positions of this scale are almost identical to those of the major pentatonic scale. The only difference is the addition of the ‘blue note’.

The blue note in the major blues scale

Although the shapes of the minor and major blues scale are the same, the function of the blue note in each scale is slightly different.

As detailed above, in the minor blues scale, the blue note adds a real element of tension to your playing. It is a totally new note that doesn’t appear in either the minor or major pentatonic scale.

The same is not true for the blue note in the major scale. The additional blue note that appears in the major blues scale is not a ‘new’ note. In fact it is just the b3 – which is a note that already appears in the minor pentatonic scale.

Let’s have a look at this in more detail:

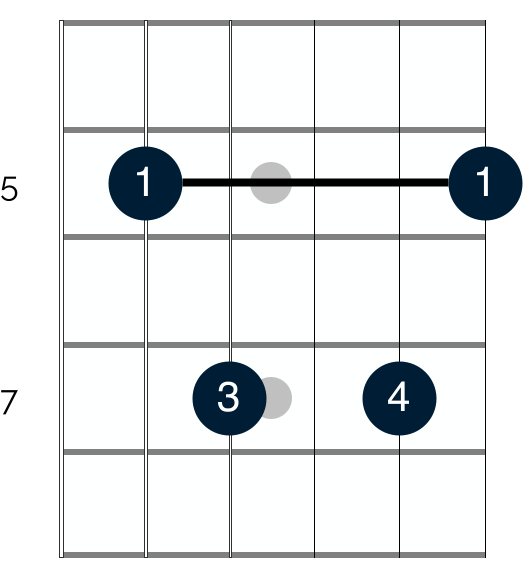

This diagram shows how the major and minor blues scales overlap on the fretboard in the key of A. It shows shape 1 of the minor blues scale, and shape 2 of the major blues scale.

The notes in white are those that appear in both scales. The notes in dark blue are those which appear in just the minor blues scale. Those in light blue are the notes which appear in just the major blues scale. Finally, the notes in yellow are all of the blue notes that appear in both scales.

Let’s compare those with the notes that appear in shape 1 of the minor pentatonic scale:

The notes highlighted in yellow here are the blue notes from shape 2 of the major blues scale. And as you can see, these are notes which already appear in the minor pentatonic scale.

So if you have ever mixed the minor and major pentatonic scales in your playing, then you will have inadvertently played the major blues scale.

How to use the major blues scale

The good news then, is that you have most likely already played the major blues scale. The next step though, is to do this in a way that is a little more intentional.

There are two significant elements to consider here. The first is understanding how to use the major pentatonic scale.

Like the minor pentatonic and minor blues scale, the major pentatonic and major blues scale can be used interchangeably. However compared with using the minor pentatonic and minor blues scale, it is not so easy to use the major pentatonic (and by extension, the major blues scale) in your playing.

This is because unlike the minor pentatonic and minor blues scale, there are a few more rules to follow when you use the major pentatonic scale. And the same rules apply when you use the major blues scale.

The 2 main rules to keep in mind when you use the major pentatonic and major blues scales are as follows:

1.) Play the scale over major & dominant chord progressions

The minor pentatonic and minor blues scale are so versatile because you can use them over both major and minor chord progressions in most blues and rock contexts.

As noted earlier, this defies the rules of music theory. Mixing minor and major tonalities shouldn’t really work or sound good. But in fact it sounds brilliant. And more than that – it has created a sound that we now associate with blues and blues rock music.

The opposite is not true for the major pentatonic scale and the major blues scale. If you try to play the major pentatonic or major blues scale over a minor chord progression, it will not sound good. This is because the notes of the major scale clash with those found in minor chords. And this creates a harsh dissonance.

So, when you are soloing using the major pentatonic or major blues scale, keep in mind that you are not able to use it over minor chords. Instead, use it over major chord progressions and chord progressions that use dominant chords.

If you aren’t yet familiar with dominant chords, then I would recommend first reading this article that I wrote on the topic. This explains dominant 7th chords – which appear in most 12 bar blues progressions – in more detail.

2.) Avoid The IV Chord

The second reason that most guitarists struggle to implement the major pentatonic and major blues scales, is that even within a 12 bar blues context, it is more difficult to play these scales over the whole progression.

I cover the 12 bar blues form in a lot more detail here – so if you are new to this material, I would recommend reading that article first. As a quick recap though, a typical 12 bar blues progression is comprised of the I, IV and V chords in any given key.

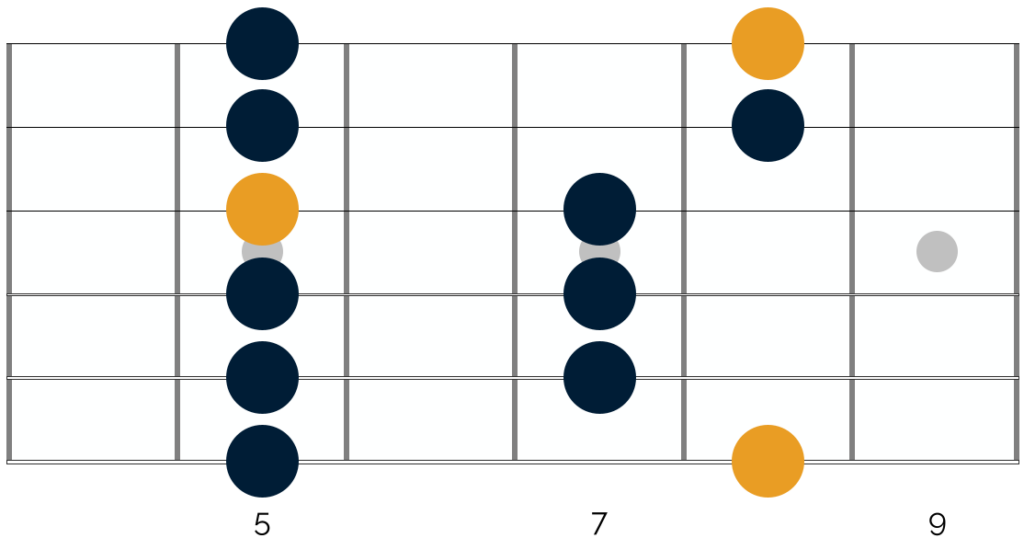

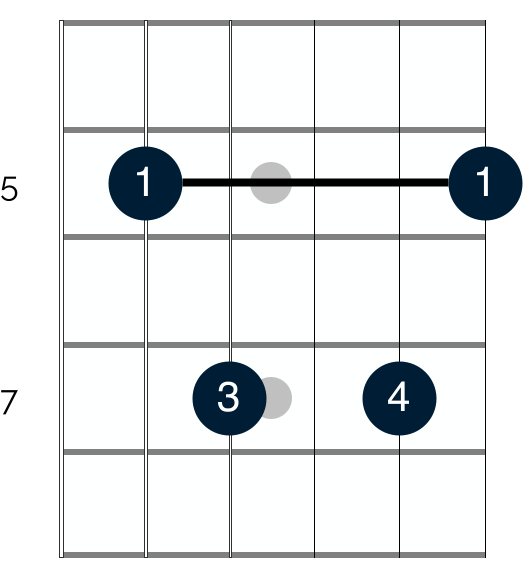

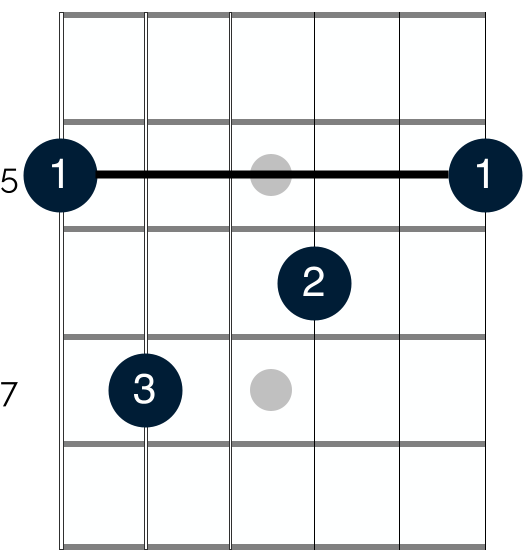

In the key of A, this gives you the chords of A7, D7 and E7. Below I will discuss the different options you have when soloing over a 12 bar blues progression. But for now let’s focus on that D7 chord. There are numerous different ways to play this chord, but one of the most frequently used is like this:

It is difficult to play the major pentatonic or major blues scale over this chord, because there are certain notes within the scale that clash with those in the chord. In the key of A major for example, the major pentatonic scale contains the note C#. This note clashes with the C note in the D7 chord and produces a dissonant and unpleasant sound. You can see this here:

The dark blue dots show the notes that appear in the D7 chord. As you can see, many of the notes that appear in the major pentatonic and major blues scale in this position also appear in the chord. The white circles show the additional notes that appear in the major blues scale, but not in the chord.

Finally, the two yellow notes show those notes that appear in the major pentatonic and major blues scales, and which clash with the notes found in the chord. This is what it sounds like when you play that C# note against the C in the chord:

As you can hear, it doesn’t sound great. And although you can play the scale and avoid that note, it is difficult to do so.

Mixing the minor & major blues scales – Pt. I

The clash that occurs between the notes found in the major blues scale and the IV chord in a 12 bar blues progression is not musical. It does not create a bluesy sound. It just sounds discordant and so should be avoided.

I appreciate that the rules outlined above might sound complex. But once you understand them, they are easier to implement than you might think.

Here is a rough guide on how you can use the major blues scale and play it alongside the minor blues scale over a 12 bar blues progression. The example I use here is in the key of A, but you can apply this same idea to different keys.

A7

Over the I chord in a major 12 bar blues progression, you can choose to play either the minor or the major blues scale.

Both will sound great, and so the choice depends largely on the type of feel that you want to create in your solo.

To an extent, the opening bars of your solo will establish the feel you create. If you open using the major blues scale, you will establish a brighter and more upbeat sound to your playing.

Conversely, if you choose to play the minor blues scale, you will create a heavier and more edgy feel.

You can of course choose to mix the 2 scales over the I chord as well. And I cover how you can do this effectively in more detail below.

D7

As mentioned above, when the 12 bar blues progression moves to the IV chord, I would recommend playing the minor blues scale. So in the key of A major, playing the A minor blues scale would be my top choice.

Over the IV chord, you also have the choice to solo using the minor blues scale that relates to the IV chord. So in the key of A, when the progression switches to D7, you could also solo using the D minor blues scale.

Having said that, if you are just starting out with this material, I wouldn’t recommend going down that route at first. This is because it requires you to think about a greater number of scale patterns and positions on your guitar’s neck. And if you are new to these scales, I would recommend breaking down the challenge of using them into small chunks.

E7

In the key of A, the last chord to appear in a typical 12 bar blues progression is an E7.

As when you play over the I chord, here you can use both the major and minor blues scales. And as noted above, the scale that you choose will be determined by the feel that you want to create.

As is the case when the 12 bar blues progression moves to the IV chord, you also have the choice here to play the scale related to the chord. In this case that would be the E minor blues scale.

Here though, you also have the choice to play the E major blues scale. So over this chord you have a whole range of different choices. You can choose to play any of the following:

- A major blues scale

- A minor blues scale

- E major blues scale

- E minor blues scale

As before, if you are new to this material – don’t make life difficult for yourself. Don’t worry about moving to the E minor or major blues scales. Instead, just stick on the A blues scale, and experiment with moving between the major and minor versions of the scale.

Mixing the minor & major blues scales – Pt. II

If you have already been mixing the minor and major pentatonic scales in your playing, then the information laid out above won’t be anything new.

And that is great news, because once you are in a position where you know how and when to use each version of the blues scale, you can extend this idea once step further.

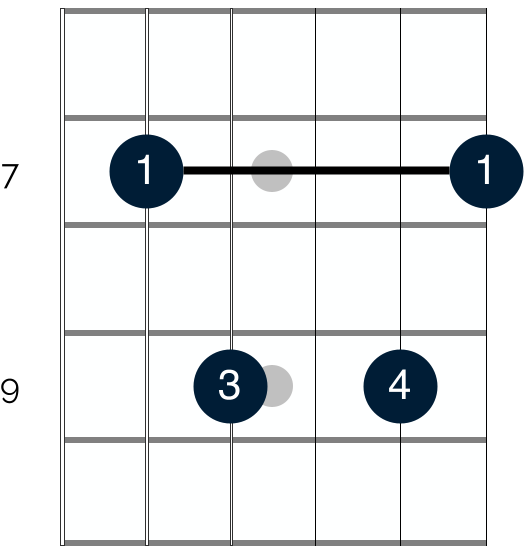

Let’s look again at how the major and minor blues scale overlap:

Still in the key of A – this diagram shows the position on your fretboard where shape 3 of the minor blues scale overlaps with shape 4 of the major blues scale.

The notes in white are those that appear in both scales. The notes in dark blue are those which appear in just the minor blues scale; and those in light blue are the notes which appear in just the major blues scale. Finally, the notes in yellow are all of the blue notes that appear in both scales.

As you can see, when you combine the 2 scales together, you end up with a wide range of notes from which to choose. And importantly, on a number of strings, there are 4 or even 5 notes positioned in a line.

This gives you the option to play ascending and descending runs of chromatic notes, which when used correctly will give your playing a sophisticated and jazzy feeling.

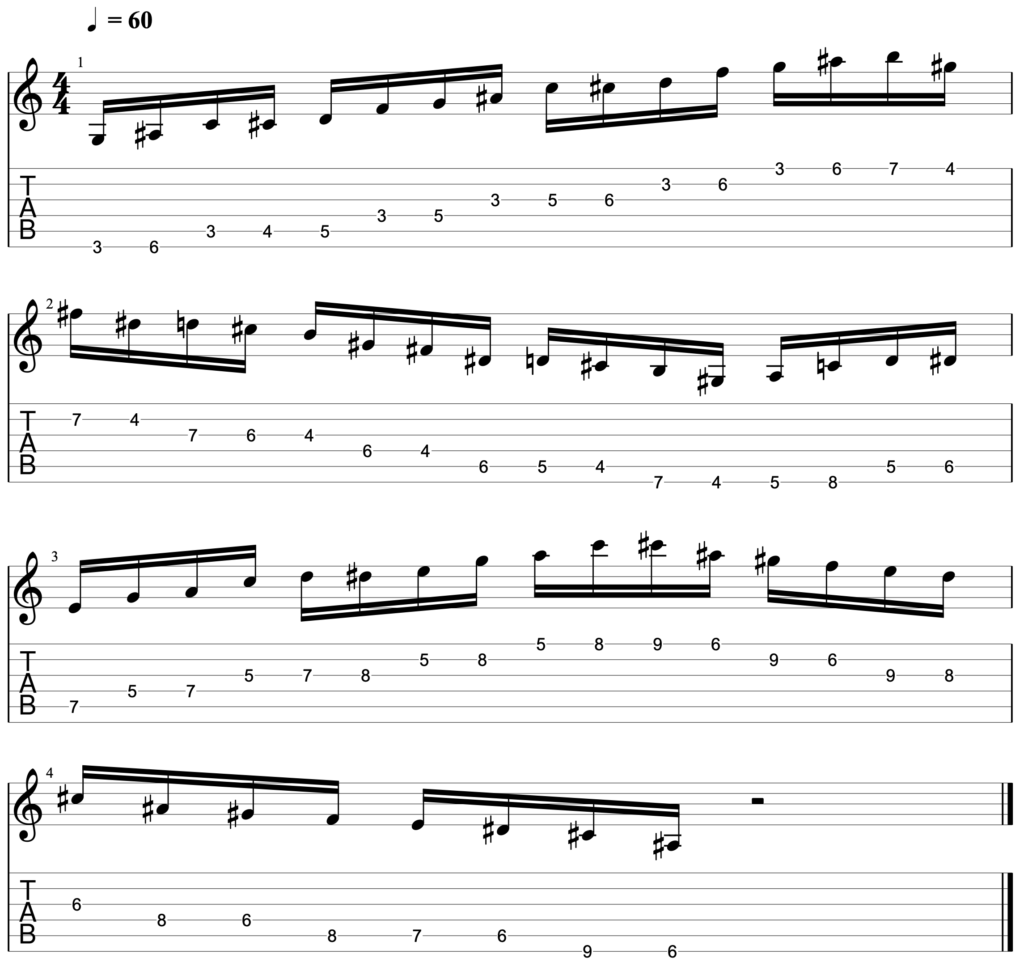

Here is an example lick to help bring this idea to life:

This is what the lick sounds like:

There is quite a density of chromatic runs in this short lick. And in fact there are more than I would normally include within a blues context.

But I hope this helps to give you an idea of how to incorporate these ideas in your own playing. Experiment with different phrases and licks in your solos until you strike a balance that works for you.

The blues scales in context

To provide you with further examples to help you get to grips with the material here, below are some examples of famous riffs and guitar solos that use the blues scale in different contexts:

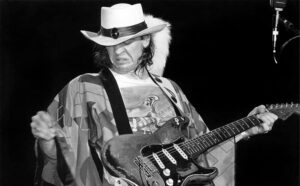

- Throughout the song ‘Pride and Joy’, Stevie Ray Vaughan uses the E minor blues scale (tuned down a half step to Eb).

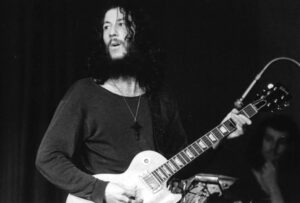

- The iconic riff in the song ‘Sunshine Of Your Love’ by Cream is based around the D minor blues scale.

- In the Aerosmith song ‘Walk This Way’, the riff is constructed using the E minor blues scale. The various different guitar solos in the song are built around the C major and minor blues scales, as well as the E minor blues scale.

- The riff in the Led Zeppelin song Heartbreaker is based around the A and B minor blues scales.

- The riff in the song Roadhouse Blues by The Doors is based around the E minor blues scale.

The songs listed above are just some examples. There are a whole range of famous blues and blues rock songs that have solos and riffs that are constructed using the blues scale.

But listen to these riffs and solos and try to hear the additional notes of the blues scale being played. This will help you to develop a sense of how the scale sounds within the context of a song. And this will be useful when you start to create your own solos and improvisations.

How to practice the blues scale

Given the importance of the blues scale in blues and blues rock music, I would recommend always including it in your guitar practice routine in some capacity.

There are 2 exercises that I regularly use to practice it. These are as follows:

Exercise 1

This first exercise works very well if this material is new to you and you are just getting to grips with the shapes listed above. It is a very straight forward exercise. It simply involves playing the scale shapes slowly along to the click of the metronome set at the lowest tempo you can manage.

This serves 2 purposes. Firstly, it helps you to consolidate the minor blues scale shapes all over the neck of your guitar. Secondly, it helps you to develop greater rhythmic precision.

It is great to be able to play quickly, and if you are looking to play faster, then in this article here, I outline 7 exercises that will help improve your playing speed. But if you want to be a great guitarist, you need to have an amazing sense of timing. This will help you to play in the pocket and lock into the groove.

To perform this exercise, set your metronome at a fairly low tempo of around 60 or 70 BPM. Go through your major and minor blues scale shapes (which incidentally are the same – they just appear in different parts of the fretboard), and play 2 notes for each click of the metronome. Do this in a variety of different keys.

Start at a level where you can comfortably play your scales in time. You should aim to play each note perfectly in sync with the click or beep of your metronome.

Once you have that nailed, reduce the BPM by a couple of beats and repeat the exercise. Stick at this level until you can play each note in time. Reduce the BPM again and keep going. It will become more challenging the more you reduce the BPM.

I often use this as a warm up exercise to get my fingers moving and to improve my sense of timing and rhythm.

Exercise 2

The second exercise I like to include in my practice routine is slightly more technical. It involves taking each shape of the blues scale, and playing them chromatically up and down your fretboard. This is what the exercise looks like using the first shape of the blues scale:

Start the exercise by playing shape 1 of the blues scale. Begin at the 3rd fret, and work your way up the neck as shown above, until you reach the 15th fret.

Then without pausing, work your way back down to the 3rd fret. Once you have done that using the first shape of the blues scale, move on to the second. Go through all of the scale shapes in this way.

I recommend performing this exercise along to the click of a metronome. Except this time play 4 notes for each click of the metronome. This is what the exercise sounds like, playing 4 notes per click at a tempo of 60 BPM:

Like the first exercise, this helps you to consolidate your scale shapes. And it helps you to get used to playing them all over the fretboard.

Additionally, this exercise helps you to build speed and stamina in both your picking and fretting hands. This is because you don’t break at all as you move between the different scale shapes.

Unlike the first exercise, here I would recommend choosing a BPM that feels fast but manageable. You want to stretch yourself, without sacrificing accuracy and precision.

Once you can play all of the shapes at a particular tempo, up the BPM by a couple of beats. It will become more challenging the higher you push the BPM.

Putting it all together

I appreciate that there is a lot of information to take in here. So if you are feeling confused or overwhelmed, here are the key points to remember:

- There is a minor blues scale and a major blues scale. The minor blues scale is very similar in construction to the minor pentatonic scale. It just contains one extra note. The major blues scale is very similar in construction to the major pentatonic scale. It just contains one extra note.

- In both versions of the blues scale, this additional ‘blue’ note is a chromatic note. Using it adds tension and a distinctly bluesy feel to your playing.

- You can play the minor blues scale in all of the same contexts you currently play the minor pentatonic scale.

- You can play the major blues scale in all of the same contexts you currently play the minor pentatonic scale.

- Use the blue note sparingly. It is there to add tension and an element of chromaticism to your playing. Used in this way, the blues scale sounds brilliant. But if you overuse it, your lead guitar playing will suffer.

As a final piece of advice – break down the challenge of using the blues scale into manageable chunks. If you try and take all of this information in straight away, you are likely to feel a little overwhelmed. So take things slowly.

Start with the minor blues scale and get comfortable using it in place of the minor pentatonic scale. Once you have done that, move your attention to the major blues scale. Again, get fully comfortable with that, and then really work on combining the two versions of the scale in your playing.

Do this, and you will be amazed at what it does for your playing. It will make your solos sound much bluesier and more varied. It will give your playing extra edge and depth.

Good luck! Let me know how you get on, and if you have any more in depth questions on the subject please do get in touch. Drop a note in the comments section, or send me an email on aidan@happybluesman.com. I’d love to help.

References

YouTube, Andys Lab, Guitar Music Theory, Music Stack Exchange, Your Guitar Academy, Jazz Guitar

Images

Image of Stevie Ray Vaughan – ©RTBusacca / MediaPunch (Taken from Alamy)

Donner Deal

Responses

[…] scale is a five-note scale. The blues scale adds the sixth note. This is a flattened fifth, and it's the "blue note" that gives the scale its distinctive bluesy sound. But what is a flattened fifth? The fifth in a […]

Why can John Hurt get away with adding the major 3rd chord (E in the key of C) to the 1-4-5 progression (i.e., in Cocaine Blues) when I thought the 3rd chord in the key should be iii or minor. And can I play major or minor blues scale over it?