If you want to broaden your understanding of the guitar and develop a greater sense of freedom when moving around the fretboard, I would recommend learning the chromatic scale.

The chromatic scale is not one that you are likely to use in your playing with any regularity. In fact the purpose that it serves is largely theoretical, rather than practical. However despite this, it is an immensely useful scale to understand.

It is not easy to to navigate around your guitar fretboard. In my experience, it is one of the biggest challenges that most guitarists face.

A lot of players don’t even attempt it, and for some guitarists, just thinking about how and where to start with learning the logic of the guitar fretboard causes them to feel overwhelmed.

This can cause frustration over time, as players end up ‘trapped’ in certain areas of their neck. They don’t feel comfortable to move around, and so they end up playing the same patterns and licks.

If you feel you are in this position, then learning the chromatic scale is a great first step to helping you ‘unlock’ your fretboard. Learning the chromatic scale will help you to:

- Play in all 12 musical keys without fear of hitting the wrong notes or playing out of key

- Move confidently around the neck of your guitar when improvising and soloing

- Play chords in different areas of your guitar fretboard, to create different feels and chord voicings

- Solo all over your fretboard, and create your own patterns, without having to rely on the same old licks and phrases

As such, if you feel stuck in a rut with your playing, or frustrated that you are stuck in certain patterns, learning the material outlined here will help you to move up to the next level. It will also help you to develop a solid understanding of some of the fundamentals of music theory as it applies to the guitar.

So with that in mind, let’s get into it! Here is everything you need to know about the chromatic scale, and why it is important:

The musical alphabet

Before we look at the chromatic scale in greater detail, it is first worth understanding the concept of the musical alphabet.

All of the notes that you encounter in Western music are represented by a letter from the alphabet. But unlike the alphabet that we use to construct words, within the musical alphabet, there are only 7 letters. These are as follows:

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

G represents the end of the musical alphabet. So once you reach the letter or note of G, the alphabet resets and you end up back at A. In other words, the musical alphabet does not contain the notes of H, I or J etc.

As a result, you will not find the notes of H, I or J on your guitar fretboard. You will however find the notes of A, B and C etc.

Having said that, there are some additional notes you need to consider. This is because Western music contains 12 notes and not 7. Yet as you may have noticed, the letters A – G account for only 7, rather than 12 notes.

Sharps & flats

The remaining 5 notes are accounted for by what are called sharps and flats. Sharps are denoted in music with the following symbol: #. Flats are denoted in music with the following symbol: b.

Sharps and flats are notes that exist in between many of the notes listed above. For although the letters noted above sit next to each other in the actual alphabet, they do not sit directly next to each other in a musical context.

Most of the notes of the musical alphabet are separated by what are known as tones (which are often also referred to as ‘whole steps’). There is a tone between the notes of A and B for example. And the same is true for the notes of C and D.

These tones are made up of 2 smaller semitones (often referred to as ‘half-steps’). Most of the letters of the musical alphabet are separated by two semitones. They do not sit directly next to each other. Which then begs the question, what exists between these notes?

The answer here, is a note that is one semitone higher than the first note, and one semitone lower than the second note. Between the notes of A and B for example, there is the note of A# (A sharp) or Bb (B flat).

This is just one note, but it can be named in two different ways. And these same notes exist between many of the notes of the musical alphabet. Between C and D for example, you will find the note of C# or Db.

Understanding this can be a little tricky at first. But surprisingly, I find that using a mathematical example makes it easier to comprehend.

Let’s imagine for example that A is 1 and B is 2.

A# or Bb is the note that sits directly in the middle of these two notes. So we can view it as 1.5.

You can add 0.5 to 1 (A) and get 1.5 (A#). Equally, you can subtract 0.5 from 2 and also get 1.5 (Bb).

The end point is exactly the same. It is just that the process we have used to reach it is different. And it is the same with naming sharps and flats. A# and Bb are the same note and they sound exactly the same. We have just chosen to name them differently. The same is true of the sharps and flats that appear between the various notes of the musical alphabet.

In an actual musical context – when you are playing in a key – it is not quite so straightforward. This is because there is a naming convention which dictates when it is appropriate to call a note A# and when Bb etc.

But there is no need to worry about that yet. For now, the most important thing to remember is that the pitch of these two notes – and those similar to them – are the same.

The chromatic scale

When we add in all of the sharps and flats that exist between the notes of the musical alphabet, we end up with 12 notes. These make up the chromatic scale, and comprise all of the notes used in Western music. The 12 notes in the chromatic scale are as follows:

| A | A#/Bb | B | C | C#/Db | D | D#/Eb | E | F | F#/Gb | G | G#/Ab |

There are a few key points to note here. The first of these is that not all of the letters of the musical alphabet have sharps and flats.

Specifically, there is no B# or E#. And so by extension, there is no Cb or Fb. They do not exist. B# is just the note of C. And Fb is just the note of E. The 12 notes in the table above are the only notes that you will encounter in Western music.

And between each of these notes is a semitone. So between A and A# is a semitone. And between A# and B is another semitone. As a result, between A and B there is a tone. However between both B and C, and also E and F, there is only a semitone. This is because there is no B# or E#.

This is important to remember. When I first learnt this material I found it difficult to remember which notes were missing sharps and flats. The trick I used, was to recall my favourite Beatles song – ‘Let it BE‘.

Hopefully that works for you too. If not though, try and develop an easy method of remembering that neither B or E have sharps.

The chromatic scale on your guitar fretboard

When you take the notes from the table above and play them in order, one after the other, you end up with the chromatic scale.

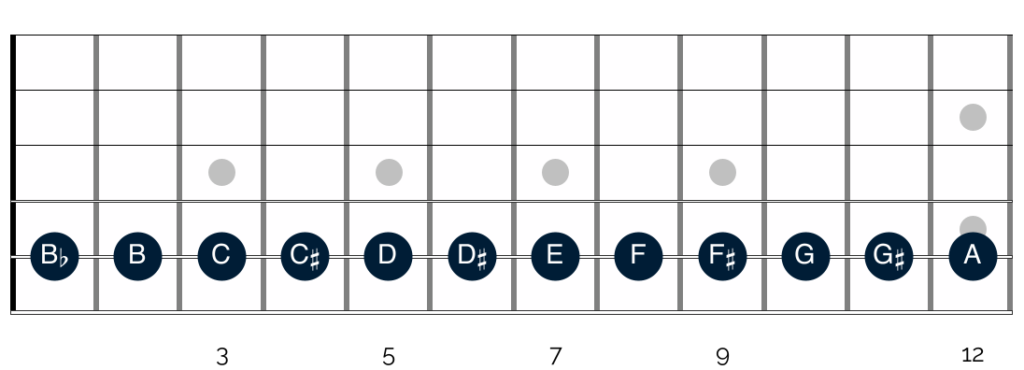

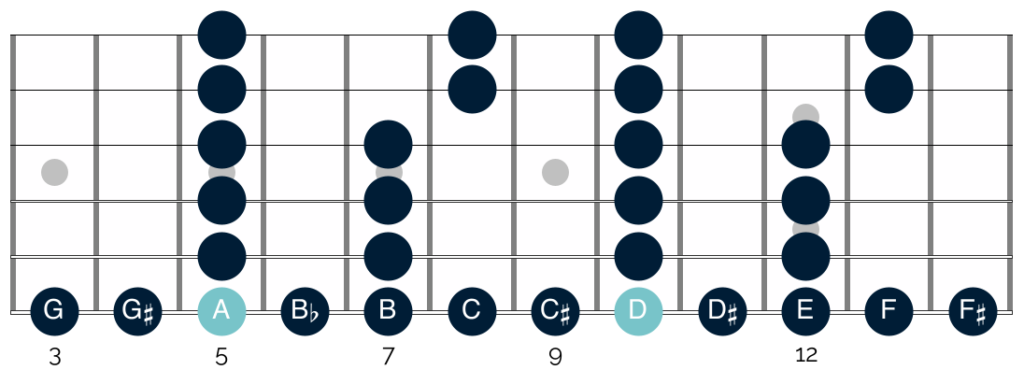

It is difficult to fully grasp these ideas out of context. But when you apply them to your guitar fretboard, understanding the theory becomes much easier. This is what the chromatic scale looks like when we start on the note of A, played here on the open A string:

By looking at the chromatic scale laid out in this way, there are two initial points we can deduce about our guitar fretboard. These are as follows:

- Each fret on the A string represents one semitone. So every time you move up or down 1 fret, you are moving up 1 semitone. Likewise, if you move up or down 2 frets, you are moving up or down a tone.

- By the time you reach the 12th fret on the A string, you have played all 12 notes in the chromatic scale. By extension you have played each of the 12 different notes used in Western music.

Now luckily, these points apply to every string on your guitar fretboard. So you don’t need to learn any new rules or logic when you are playing on different strings.

On every string, when you move up or down 1 fret, you are moving up or down 1 semitone. And again, no matter which string you start on, by the time you reach your 12th fret, you have played all 12 notes of the chromatic scale.

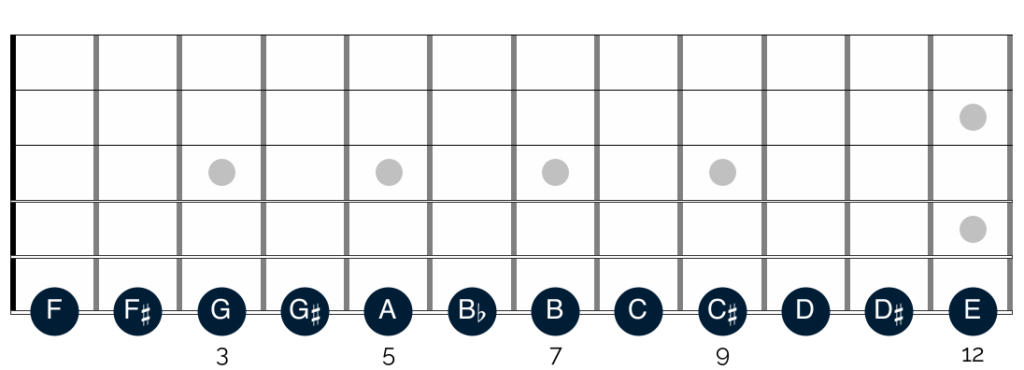

The only difference is that on each string, you start the chromatic scale on a different note. Let’s look at this on the low E string:

Again here you can see that there is a neat logic to the structure of the guitar fretboard. You start with the note of E when you play the open string and then every time you move up 1 fret, you move up to the next note in the chromatic scale.

And again, by the time you reach the 12th fret, you have covered all of the 12 notes in the scale.

Beyond the 12th fret

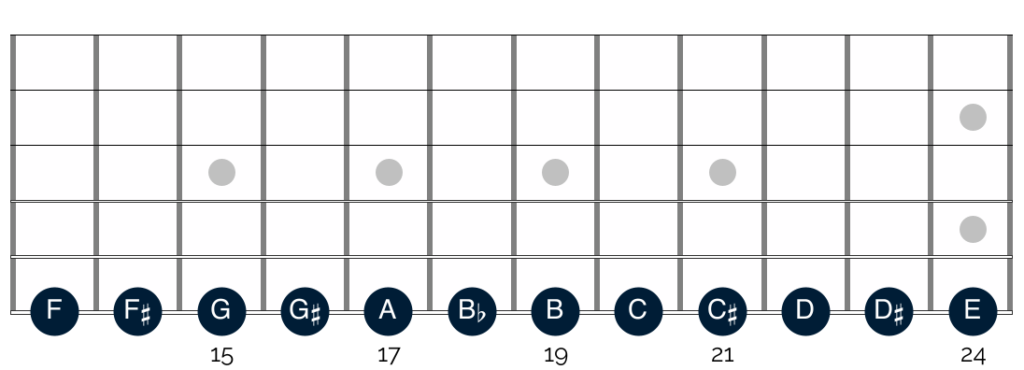

At this stage, you might be wondering what happens beyond the 12th fret of the guitar fretboard. And the good news here is that the pattern of notes is nice and easy to learn.

As noted above – and as you can see from the neck diagrams – by the time you reach the 12th fret, you have returned to the note of the chromatic scale on which you started.

On the low E string for example, you start by playing the open E string. By the time you reach the 12th fret, you are back on E. This is the same note, but now you are playing it one octave higher.

However in the context of the chromatic scale, the note is the same. And so then, are the notes that follow. In other words, the order of the notes after the 12th fret are exactly the same as those before the 12th fret.

Let’s look at this on the low E string:

As you can see, the notes on your guitar fretboard repeat themselves after the 12th fret. To best illustrate the point, the diagram above shows a guitar with 24 frets. If you play a guitar with 24 frets, then you can play 2 octaves of the chromatic scale, on every string.

But even if your guitar has 21 or 22 frets, you can still view your guitar fretboard as being split into two parts. It is for this reason that on the vast majority of guitar fretboards, there are two fret inlays at the 12th fret.

Using the chromatic scale

Up to this point we have covered what the chromatic scale is and how it is constructed. But as you might have guessed from the fretboard diagrams above – the chromatic scale does not form practical shapes on the fretboard, and as such it is not one that you are likely to use in a practical playing context.

This then begs the question – how do you use the chromatic scale? And what are the benefits of knowing the scale?

In short, the chromatic scale provides you with a pattern of notes that you can use to work out all of the notes on your guitar. It gives you a fundamental understanding of how your guitar fretboard is constructed, and the relationship between frets, semitones and tones.

This helps you in the following ways:

Playing in different keys

If you know where different notes appear on your guitar, then you can easily play in different keys. Let’s say for example that you typically improvise and solo in the key of A. Well, by using the chromatic scale, you can take all of the licks and phrases that you play in the key of A, and transpose them to the key of B, C or D etc.

Let’s look at this in a little bit more detail:

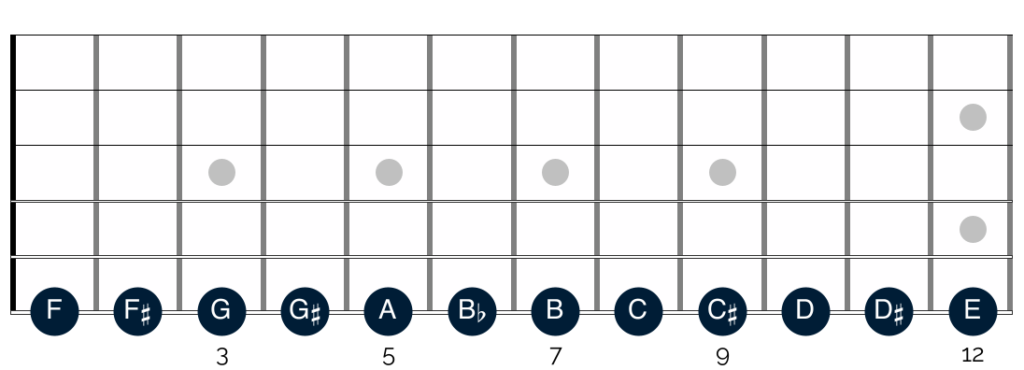

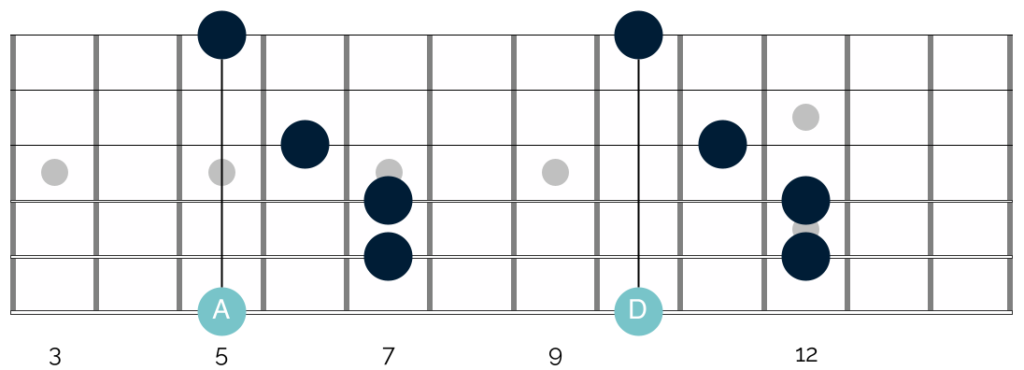

The above diagram shows the notes of the chromatic scale as they appear on the low E string. It also shows the shapes of the A minor pentatonic scale and the D minor pentatonic scale, respectively. Hopefully you can see that the scale shapes are the same, and the only difference is where they appear on the fretboard.

As such, if you are used to playing in a particular key, understanding the chromatic scale helps you to easily move all of your ‘go-to’ licks and phrases into another key.

All you need to do is find the note of the key in which you are playing on your low E string. Start playing the first shape of the minor pentatonic scale on that note, and you will now be playing in that new key.

For example, if you want to play in the key of C, all you need to do is find the note of C on your 6th string. Start playing the first shape of the minor pentatonic scale, starting on that note of C.

You then know where your first scale shape is, and can then move to find the remaining shapes of the scale. In this way you can take all of your licks and phrases, and play them in any key.

Playing chords

You can apply the same idea to move barre chords all across your fretboard too. Again we can see this if we look at an example on the fretboard:

Barre chords are not typically presented in this way, so the diagram might at first look a little confusing. However what you will see is that in fact all it shows is an A major chord, and then a D major chord.

As in the example above, the shapes of the chords are exactly the same. The only difference is the position in which they appear on the fretboard.

So if you know how to play an A major chord, then by combining that with your knowledge of the chromatic scale, you also know how to play a B major, C major and D# major chord etc.

In this way, understanding how the chromatic scale works empowers you to play a variety of both lead lines and chords all over your fretboard.

Using the low E and A strings

To use the chromatic scale in a practical context, you don’t need to learn the notes of the scale, across all 6 strings. In fact all you need to do is learn the notes of your chromatic scale on your low E and A strings. There are two reasons for this:

Firstly, the majority of scales and barre chords have their root notes on the low E and A strings. So learning the notes on these strings will help you to move scale and chord shapes all over your fretboard with ease.

Additionally, and as I explained in much more detail in this article here – you can build octave shapes from the low E and A string to work out the remaining notes on your guitar.

This helps you to connect notes from your low E and A strings to other strings on your guitar, without you having to learn every single individual note on the fretboard.

So if you want to start using the chromatic scale in practice, but you don’t have the inclination to learn the notes of the scale on every string, then don’t worry! By learning the notes of the chromatic scales on the low E and A strings, you can get started quickly using it in a practical context.

Closing thoughts

Well there we have it – what the chromatic scale is and how you can use it in your playing.

As is often true of some of the more theoretical elements of guitar playing, the information contained here is not exhaustive. For example, I would also argue that understanding the chromatic scale will also help you to better understand intervals and scale construction.

However, those are both lengthy topics. They require much greater depth and explanation, and are beyond the scope of this article. As such, I will cover them in more detail in a future article.

In the meantime though, I hope that the information here helps to get you started with the chromatic scale. From a theoretical point of view, the chromatic scale is fundamental in helping you understand music theory as it applies to the guitar.

From a practical point of view, it helps you to appreciate the logic of your fretboard. And this in turn will benefit your lead and rhythm playing, and make you a more skilled and well-rounded musician.

Good luck! Let me know how you get on, and if you have any questions at all please do get in touch. Drop a note in the comments section, or send me an email on aidan@happybluesman.com. I’d love to help!

Responses

Hi, just wanted to let you know I’m really enjoying your site!

Some of the best stuff has been your focus on slide techniques.

If you are looking for story ideas, I’d love to see a pair of stories on selecting guitars for electric and acoustic slide. This would hopefully include various price points for someone who doesn’t want to commit a ton of money for devoting a guitar exclusively to slide, as well as appropriate string heights and other important considerations when selecting a slide axe.

Thanks again for your excellent work, and I’m looking forward to more great stories from you in the future!

Scott

Thanks so much for the kind words Scott, they made my day! I am so glad to hear that you have enjoyed the articles and found them useful. And that’s great to know about the material on slide. As it happens I recently bought a Squier Telecaster that I plan on upgrading and setting up specifically for slide playing, and so I will definitely get writing articles on adjusting the string heights and altering the set-up for slide.

In the meantime though if there is anything I can help with, or if you have any questions about your playing or gear, just send them over. You can reach me on aidan@happybluesman.com and I am always around and happy to help