Guitar chord theory is not an easy topic. In fact, most of the guitar players that I encounter are reticent to learn guitar chords at all; let alone to learn guitar chord theory.

For the vast majority of my playing career, I took the same approach. I totally neglected chords and rhythm playing all together. I spent huge amounts of time and focus learning how to play lead guitar like Stevie Ray Vaughan and Gary Moore. And yet I didn’t even know how to play the most basic of chords.

Some years ago I made a concerted effort to bring up this weaker area of my playing. I have since put a lot of time and effort into building my knowledge of guitar chords and understanding guitar chord theory.

And thankfully, doing so has had a profound effect on my guitar playing. I now feel much more comfortable and confident playing a range of guitar chords all over the fretboard. But one additional and significant benefit, is that my lead guitar playing has also improved.

This is because chords provide the foundation for all of the music that you play. When you play a guitar solo, you are most likely playing that solo over chords.

So even if you have no interest in playing chords or rhythm guitar, understanding how chords are formed and how they function will do a huge amount to improve your lead guitar playing.

It will help you to create more sophisticated solos. It will also allow you to play alongside the track you are accompanying, rather than on top of it. And this will make your solos sound more melodic and effective.

Finally, if you have any ambitions for writing your own music, I would strongly recommend learning the basics of guitar chord theory. It will help you to construct interesting and impactful chord progressions that will represent the type of music you are trying to create.

Guitar chord theory is a broad topic, which goes well beyond the scope of a single article.

As such, here I will be covering the basics. This will give you the fundamentals of guitar chord theory you need to become more comfortable with chords and how they are constructed. Over time you can build on this to take your guitar chord theory knowledge to the next level.

Before we get into it, I think it is worth noting that this is not an article full of chord diagrams that you can actually use in your playing. I will provide those in future articles.

As such, the information outlined here is largely theoretical, rather than practical. Yet once you understand this information, it will make learning different chords and using them in your playing much easier.

So whether you are looking to improve your rhythm guitar skills, write your own music, or develop as a musician more generally, I hope you find the information included here useful. Here are the basics of guitar chord theory:

Understanding the major scale

To understand guitar chord theory and how guitar chords are created, we need to look at the major scale. This might not seem particularly relevant at first.

But in fact it is the major scale which provides the foundation for Western music, including the blues. And it is in looking at the major scale that we can begin to understand guitar chord theory.

If you are new to the major scale, then I would recommend reading my article ‘Getting Started With The Major Scale‘ before continuing here. In that article I cover the major scale and its shapes in depth.

As a brief recap though – the major scale is a 7 note scale. Every scale in music has a scale ‘formula’. And the scale formula of the major scale is as follows:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Each of the numbers above relates to a note from within the major scale. 1 is the first note of the scale, 2 is the second note of the scale, and so on. These numbers are also referred to as ‘degrees’ of the scale. In the key of C, the notes of the major scale are as follows:

| C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

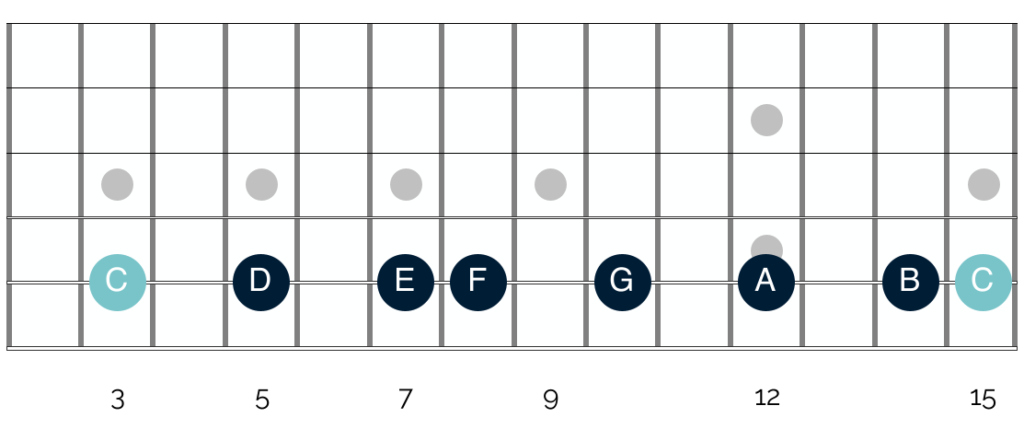

This is what the notes of the C major scale look like when you play them laterally across your fretboard:

In proper theoretical terms, a chord is a collection of at least 3 notes which are played simultaneously.

As such, if you want to create a chord, you need to ‘stack’ together at least 3 notes from the major scale.

However it isn’t just a case of picking out random notes from the major scale. There is a logic to chord construction. And although it is tricky to understand this logic at first, once you do, it will make learning to play and use chords much easier in the long run.

Creating triads

The specific notes that you stack together, the number of notes that you stack together, and the order in which you stack them together all determine the type of chord that you create.

I will dig into some of the ways that each of these elements can be adjusted in more detail below. First though, let’s look at simple chord construction.

In theoretical terms, the simplest type of chord that you can create is called a triad. As the latin name suggests, this is a chord made up of just 3 notes.

Specifically, it is a chord that is made up of 3 notes that are each separated by what is known as a third. This refers to the interval of a third.

If intervals are a new concept for you, or if you don’t yet feel totally comfortable with how they work, then head over to this article before continuing with this material. There I discuss intervals in depth, including how they work, and the different types of intervals you encounter on the guitar.

For now though, let’s look again at the C major scale:

| Note name | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Scale degree | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

This table shows all of the notes in the C major scale, in addition to the different degrees of the scale.

The notes highlighted in yellow show those that form a C major triad. As noted above, there are 3 notes contained within the triad, and each of these notes is separated by a third.

The terminology of a ‘third’ is likely to be a little confusing at first. As you have probably noticed, the notes of C and E are separated by just 1 note, not 3. The same is true of the distance that separates the notes of E and G.

Thankfully, this isn’t as complicated as it first looks. All you need to remember is that when you count the notes of the major scale, you always include the note on which you start.

If we take the example above, you can see that C is the first note of the scale, and D is the second. As a result, E is then the third note that you encounter. Similarly, when you are trying to find the next note a third up from E, you count in the same way.

Now E is the first note, F is the second and G is the third.

If you find the above confusing, then you can also think about skipping out or jumping over alternative notes in the scale. In other words, you play the note of C, miss D, play E, miss F, play G, and so on.

And that is how you form a triad. Simply pick 3 notes from the major scale, each a third apart. Play them simultaneously and you have a chord!

Intervals

Now things become a little more complicated depending on which note of the major scale you start.

In the example above, starting on the note of C and forming a triad created a C major triad. Yet this isn’t true if you start on a different note of the scale.

And this is because of intervals. As noted above, a triad is formed by taking 3 notes, all of which are a third apart. Yet this triad can sound totally different, depending on the intervals between the notes.

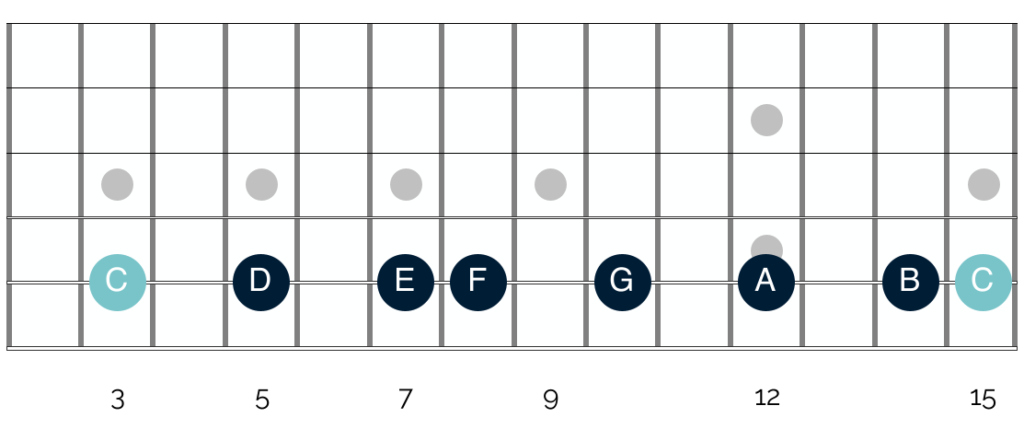

If you are familiar with the major scale, then you will know that the distances – or intervals – between the notes in the scale are all different. This is easiest to see when you look at the scale stretched out laterally across the guitar fretboard:

As you can see, there are 2 frets separating many of the notes in the scale, and only 1 fret separating others. This is very important when you begin to create triads from different notes of the scale.

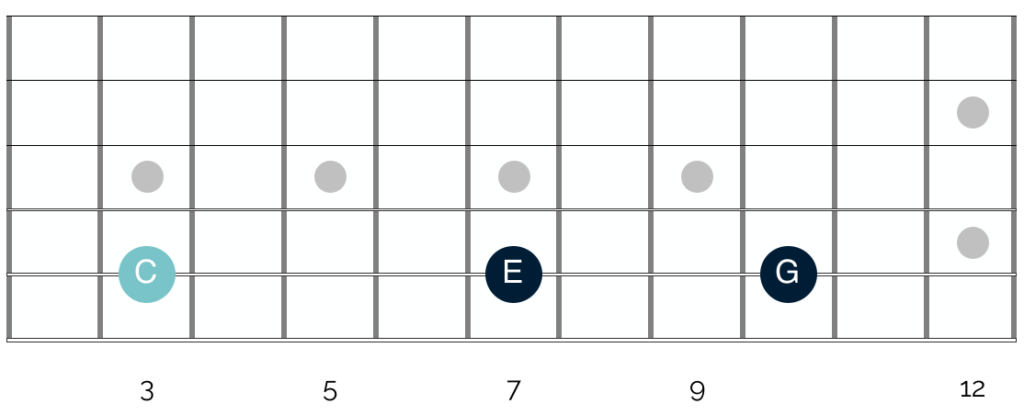

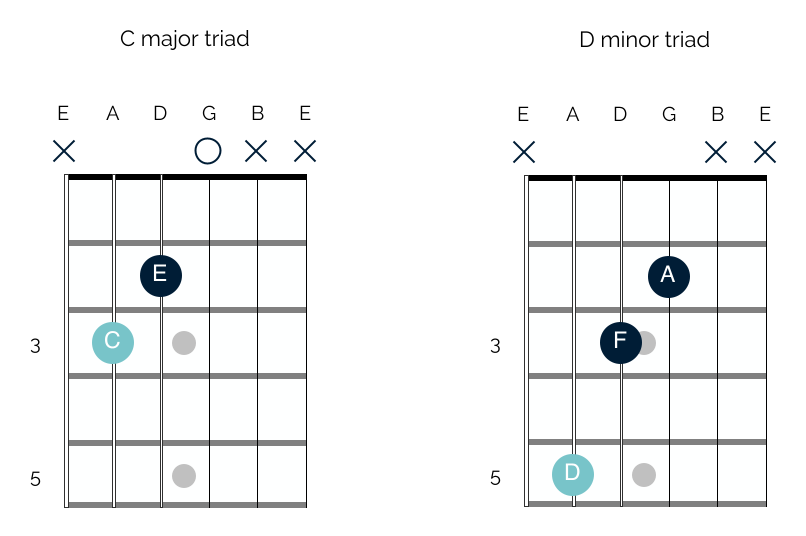

For even though the notes in any given triad might be a third apart, the actual intervals between the notes change, depending on the note on which you start. We can see this by comparing a triad starting on the note of C, with one starting on the note of D:

In this first diagram the starting note (or root note) of the triad is C, shown above in the light blue colour. As you can see, there are 4 frets separating the notes of C and E. There are 3 frets separating the notes of E and G. And between the notes of C and G, there are 7 frets.

Each fret on your guitar represents a semitone. So put another way, there are 2 whole tones between C and E, 1 and a half tones between E and G, and 3 and a half tones between C and G.

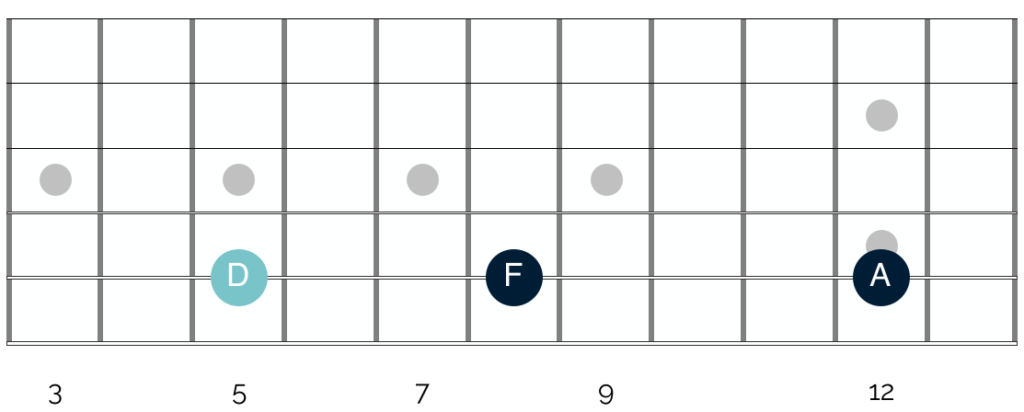

Let’s now compare this with the intervals present when we start on the note of D:

In contrast to the triad built starting on C, here the intervals between the notes are different.

Between D and F, there are only 3 frets (or 1 and a half tones). Conversely, between the notes of F and A, there are 4 frets (or 2 tones). And so just like the triad built on C, the distance between D (the root note) and the A is 7 frets, or 3 and a half tones.

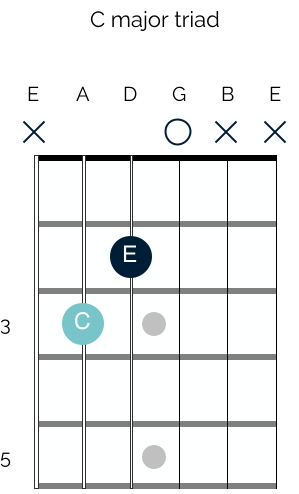

Now if we take the notes present in each of these triads and play them simultaneously, we end up with a C major triad and a D minor triad:

Here the C major triad utilises open strings. So rather than playing the note of G on a fret, here the G is played on an open string.

Before we turn our attention to the theory that determines whether a chord is major or minor, I would recommend playing both of these triads through.

And when you do so, you will hopefully be able to hear the differences in the way they sound. The major triad will have an upbeat and happy sound. Conversely, the minor triad will have a more sad and melancholic sound.

This is true of all major and minor triads, not just the specific triads shown above.

The different sounds between these two triads results from the different intervals between the notes which appear in the triads. This is an important concept when it comes to guitar chord theory and one which is covered in more depth below.

Major & minor triads

As noted above, when you form a triad starting on the note of C (in the key of C major), you form a C major triad. When you do the same but you start on the note of D, you form a D minor triad.

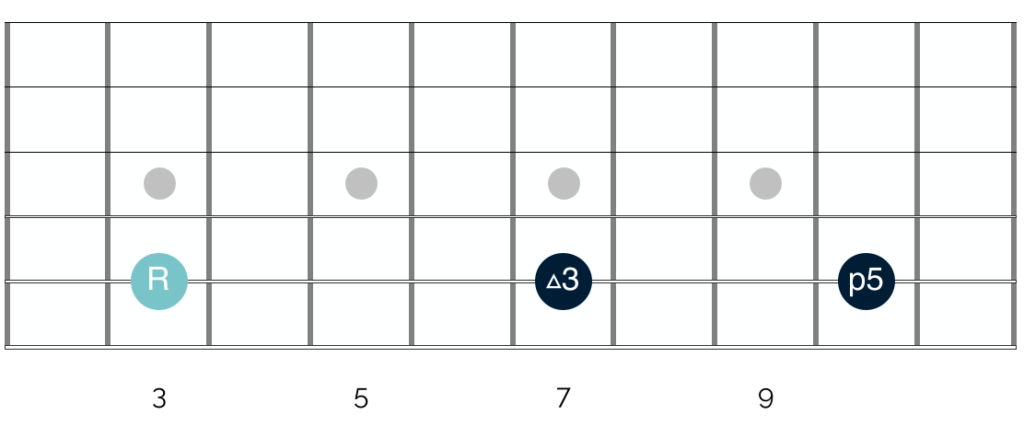

Let’s look again at how these triads appear when we look at them laterally across the fretboard:

In contrast to the diagram above, this shows the intervals between the notes in the triad, not just the names of the notes. The intervals here are as follows:

- Root

- Major third

- Perfect fifth

The first note in the chord is always referred to as the root note. And it is this note which determines the name of the chord. So the root note for a C chord is C. The root note for the chord of D is D, and so on.

A major third is always 4 frets, or 2 whole tones higher than the root note. As the name suggests, the major interval here gives this chord its major quality.

The perfect fifth is always 7 frets, or 3 and a half tones higher than the root note. Perfect intervals are associated with musical consonance and resolution. The presence of this perfect interval gives the chord a stable and harmonious sound. The chord is devoid of dissonance or tension.

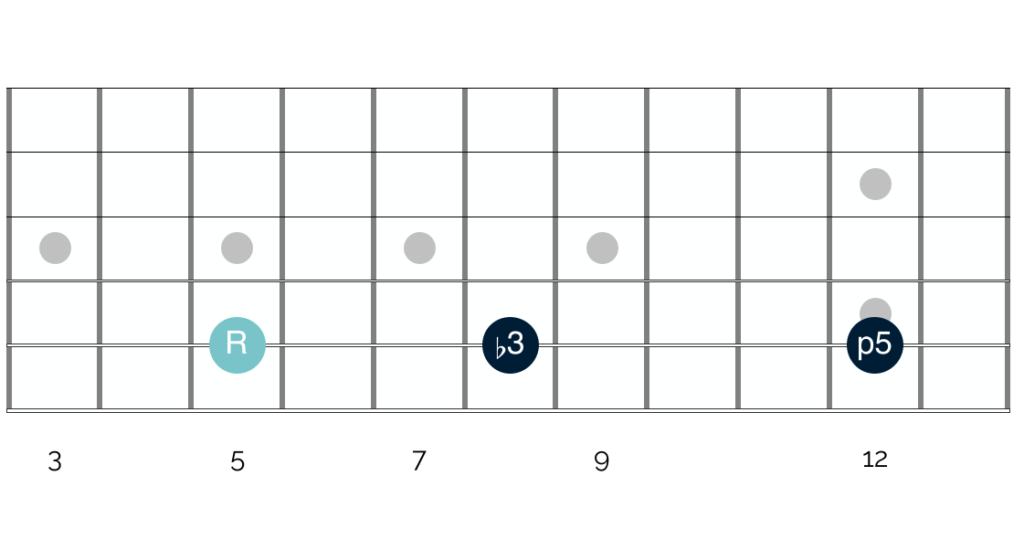

Let’s now compare these intervals with those that appear in the D minor triad:

As above, the diagram here shows the intervals between the notes in the triad, not the names of the notes. The intervals here are as follows:

- Root

- Minor third

- Perfect fifth

So, as with the major triad; this D minor triad contains a root note (in this case the note of D) and also a perfect fifth. The one key difference, is that here the chord doesn’t contain a major third, it contains a minor third.

A minor third is always found 1 fret lower than a major third. And it is always 1 and a half tones above the root note.

As you might expect, the minor interval here gives the chord its minor quality. This makes it sound slightly sad and melancholic.

However, like the major triad shown above, this minor triad also contains a perfect fifth. So although it does have a more downbeat sound, like the major triad, it also sounds stable and resolved. It does not have a dissonant or tense sound.

Harmonising the major scale

The next step to better understanding guitar chord theory is to apply this idea to all of the notes in the major scale. This will help you to appreciate the relationship between the notes in the scale and how they stack together to form different triads.

To do this, we need to return to the notes of the C major scale:

| Note name | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Scale degree | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Start on C, and form a triad by choosing 3 alternate notes from the scale (C, E and G). Then do the same but start on D and then on E etc.

When you get to the note of F – and all of the subsequent notes in the scale – just carry on in the same way.

The only change you need to make, is to go back to the notes at the beginning of the scale to create the triads, once you reach the 7th note of the scale. In the case of F for example, the notes in the triad are F, A and C. In the case of G they are G, B and D.

When you go through this exercise, keep the following points in mind:

- A major third is always 4 frets higher than the root note. The presence of this interval in a triad will produce a major triad.

- A minor triad is always 3 frets higher than the root note. The presence of this interval in a triad will produce a minor triad.

- A perfect interval is always 7 frets higher than the root note.

If you do go through this process, then hopefully you will discover two things. The first of these is that when you harmonise the major scale, you end up producing a combination of both major and minor triads.

The second is that the final note of the scale sounds quite different to the major and minor triads illustrated above. I will explain why this is the case in more detail below. Before doing so however, let’s look at what happens when you go through this process:

| Note name | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Notes in triad | C E G | D F A | E G B | F A C | G B D | A C E | B D F |

| Type of triad | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Diminished |

As you can see then, when you harmonise the major scale you end up with 3 major triads, 3 minor triads, and a single diminished triad.

It doesn’t matter which major scale you choose – they all follow the same pattern. In other words, in the key of A major or B major, or D major, the order of the triads shown above is the same.

The triads themselves are different (as there are different notes in each scale). But the order of major, minor and diminished triads is exactly as above.

This is significant, because musicians use this order of triads to create chord progressions. As such, we will look at this in further detail below.

For now though, let’s continue looking at the construction of triads. Specifically let’s look at the diminished triad that you create when you harmonise the 7th note of the major scale.

Diminished triads

As you will have discovered if you tried to harmonise all of the notes of the major scale, things become a little more complicated when you get to the 7th note of the scale.

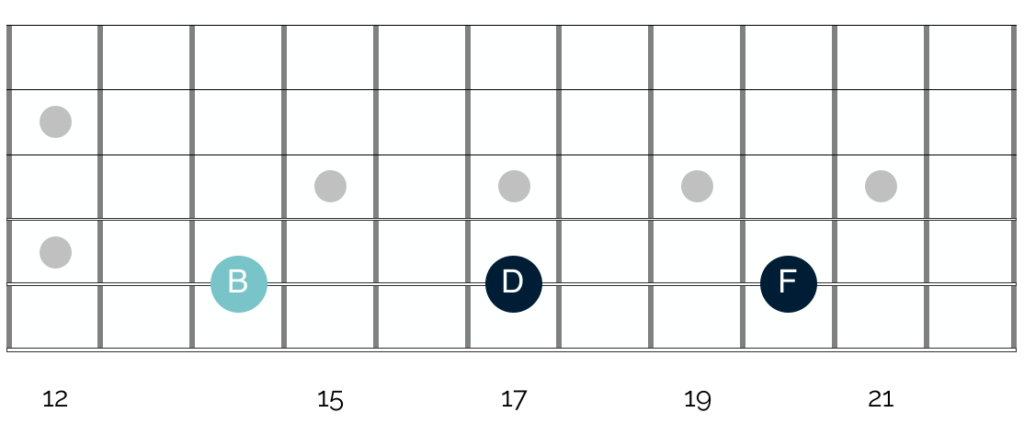

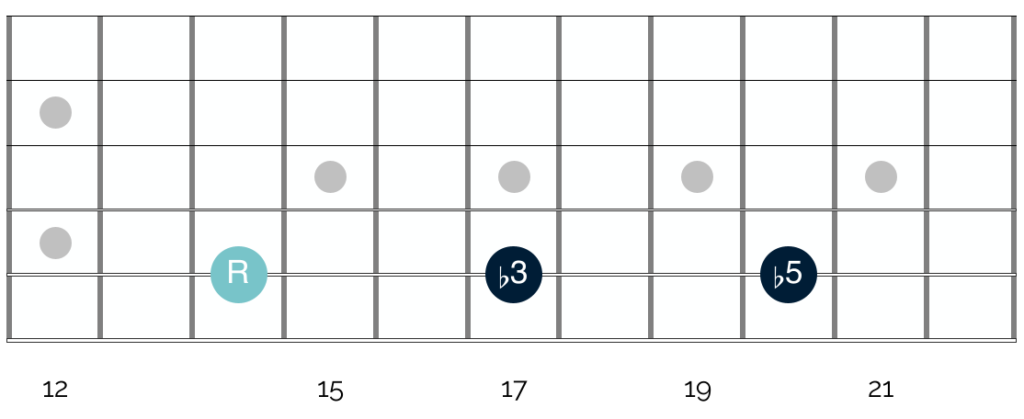

We can see this in more detail by looking at the notes in this triad on the guitar fretboard:

The above diagram simply shows the 3 notes that are present in the triad. And given that the formation of this triad is no different to any of the others in the scale, you might be wondering why it is diminished, rather than simply major or minor.

Thankfully, this becomes somewhat clearer when we look at the intervals between these 3 notes:

These intervals are different to all of the others that we have encountered up to this point. They are as follows:

- Root

- Minor third

- Flat fifth

The root and minor third are exactly the same as the other triads listed above. There are 3 frets between the root note of the triad and the minor third. The key difference is that this diminished triad does not have a perfect fifth. There are not 7 frets between the B (root note) and the F. There are in fact just 6 frets.

This is a diminished interval. And unlike a perfect interval, it has a tense, dissonant and unresolved sound.

As such, chords that include this interval are much lesson common than the minor and major triads highlighted above. That is not to say they aren’t important. Rather it is to say you will be less likely to play these compared with major and minor triads.

Triads & chords

At this stage, you might understandably be wondering how you can use this information practically. For whilst it is useful to understand what triads are and how they are formed, there is some more information we need to cover before we can use them in a practical context.

Up to this point, I have spoken about triads in their purest terms. When discussing guitar chord theory, this makes sense. But it can make it difficult to link some of these ideas and apply them to your fretboard.

This is particularly because the term ‘triad’ is more widely used by those who understand theory. And most beginner and even intermediate guitar players are fairly unlikely to encounter or use the term with frequency.

This is not true of the term ‘chord’, which tends to be one of the first terms with which guitar players become familiar.

To help you better understand what a triad is, and also how it functions in a practical context, I think it is important to first clearly define what a triad is in relation to a chord. We can then look at how to use it in a practical context.

As mentioned above, a triad is a chord made of 3 notes. And each note within the triad is a third apart. In short, this means that a triad is type of chord. All triads are chords. But not all chords are triads.

In practice though, this doesn’t mean that you have to limit yourself to playing 3 frets or strings and nothing more.

Let’s return to the C major triad shown earlier:

The diagram above shows a triad comprised of just 3 notes. I suspect that if you are new to this material, this triad shape is unlikely to be one which features a lot in your playing.

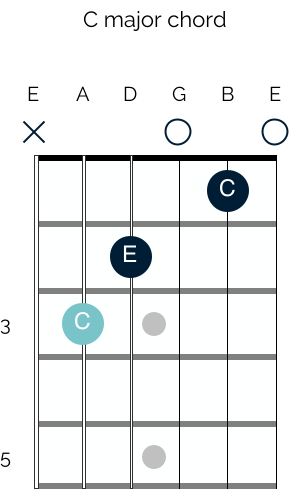

Conversely, I suspect that the following chord shape is likely to be one with which you are much more familiar:

This shows the notes which appear in a regular C major chord. Now to call the notes in the first diagram a C major triad, and those in the second diagram a C major chord is a little misleading.

The terms here can be used interchangeably. This is because they both contain the same notes.

The C major triad contains the notes of C, E and G. And as you would play it in the open position, the C major chord contains the exact same notes.

The only difference is that here some of those notes are repeated. So you end up playing C, E, G, C and E.

It is still a C major triad however, because it only contains 3 unique notes. This is true of all of the basic major and minor chords with which you are likely to be familiar.

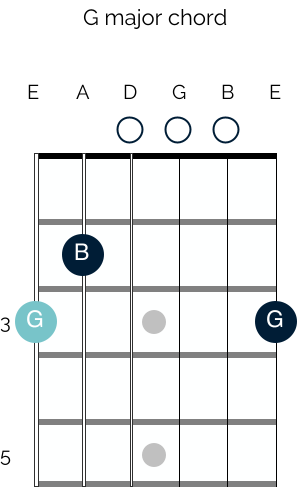

Let’s look at the chord of G major. The notes in a G major triad are G, B and D. And this is how you typically play a G major triad on the guitar:

Here the pure triad is played on the 6th, 5th and 4th strings (the note of D being played on the open D string).

When you play a G major chord however, you play all 6 strings. As you can see from the diagram above though, the only notes that you play are those in the triad. You play the open G and B strings, and then the note of G on the high E string.

Creating chord progressions

Appreciating that the triads discussed up to this point contain the same notes as simple major and minor chords is useful. It connects the material here with chords that you have most likely been using since you first started playing guitar.

And using this information, you can now look at adding these together to form chord progressions.

Let’s return to one of the tables from earlier in the article:

| Note name | C | D | E | F | G | A | B |

| Notes in triad | C E G | D F A | E G B | F A C | G B D | A C E | B D F |

| Type of triad | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Major | Minor | Diminished |

| Chord | C Major | D Minor | E Minor | F Major | G Major | A Minor | B Diminished |

| Triad / chord number | I | ii | iii | IV | V | vi | vii° |

This table shows the order of triads which are created when you harmonise the major scale. Here though I have added in an extra row which assigns a number to each of the triads. In just the same way that scale degrees are numbered, so are the triads that are formed when the scale degrees are harmonised.

Now though, the numbers are expressed as Roman numerals. Upper case numerals are used for the major triads, and lower case numbers for the minor triads.

The diminished chord is also represented by a lower case numeral. In this case however, it is either preceded or followed by a small circular symbol to distinguish it as being diminished.

Musicians use these chords to create chord progressions. Songs in the key of C for example will typically contain many of the chords in the table above.

The song ‘Let It Be‘ by the Beatles provides us with just one notable example. It is in the key of C, and the chords in the verse are as follows: C major, G major, A minor, F major. Or to put it another way, the I, V, vi and IV chords.

Guitarists and musicians often refer to chord progressions using these Roman numerals. So if you have ever heard guitarists refer to a ‘one, four, five’ chord progression – this is what they are talking about. They are simply referring to the type of triad or chord that they are playing.

In other words, if you jumped in on a jam session and you were told that the next song was a ‘I, IV, V in the key of C’ you would know the chord progression went from C major, to F major, to G major.

Beyond basic guitar chord theory

Chord progressions are not always quite so straight forward. And there are two reasons for this:

Firstly, musicians rarely stick to using chords from just one major scale. So whilst a song might be largely based around the chords in any given scale, songwriters will often change keys or ‘borrow’ chords from other keys.

And so although understanding which chords are formed when you harmonise the major scale is a significant step towards understanding guitar chord theory, there are some further pieces of theory to cover if you want to work out how different songs are created.

These are in depth and as such are beyond the scope of this article. I will however cover them in more detail in future articles. For now though, it is just important to recognise that chord progressions are not always as clear cut as I have presented them in the tables above.

Additionally, guitarists often don’t stick to using simple major and minor chords. They will add what are known as ‘chord extensions’ onto the basic triads.

These extensions don’t fundamentally change the function of the chords. In other words, minor chords remain minor, and major chords remain major. The extensions do however change the sound and feel of each chord.

These chords appear everywhere in popular music. And so you are very likely to have encountered them in the form of major and minor 7 chords, as well as dominant 7th chords. As is true of chord progressions, this is a lengthy topic that requires further depth and explanation.

The great news however is that the guitar chord theory outlined here will make it very easy to understand chord extensions.

For now though, just focus on getting to grips with the initial guitar chord theory laid out here. This material is complex and quite academic in nature.

So don’t worry if you find it challenging or confusing at first. Keep coming back to it and applying it to your guitar where possible. And I promise that with time, it will start to become clear.

Good luck! Let me know how you get on, and if you have any questions at all please do get in touch. Drop a note in the comments section, or send me an email on aidan@happybluesman.com. I’d love to help 😁

References & Images

Unsplash, Guitar Habits, Wikipedia, Hello Music Theory, Music Notes Now, Wikipedia, Puget Sound, Open Music Theory, Guitar Theory For Dummies, Modern Music Theory For Guitarists

Responses

Really enjoyed and got a lot from this, have you published the next one yet?

Thank you so much for the kind words Paul, I really appreciate it and I’m very glad to hear that you found the article helpful.

The next step of this article isn’t published just yet, but I’ve started work on it and so will be adding it to the site in the next month. So keep an eye out for that, and if I can help with anything in the meantime, just let me know. You can reach me on aidan@happybluesman.com and I am always around and happy to help! 😁

Great article. I’ve been looking for just this kind of explanation, to help me with my bass playing. Understanding chord construction will assist me in building better bass lines to complement what the guitarist is doing. Well done!

Thank you so much for the kind words Ray and I’m really glad to hear that you found it helpful. Best of luck building those bass lines! 😁

I’m beginning to under stand .using theory thank you

That is brilliant news Ike, I am so glad to hear that you found the article helpful! 😁

I absolutely appreciate your lessons here on this site. I have been playing guitar and bass at a pro level for 50 years. I had a vague grasp of these fundamentals, but after reading thru some of your plans here, it has become clear to me now what I have been doing all these years. Starting at age 10, early on I grasped the scales and chord patterns but never knew the science or math behind the theory. Thank you very much.

Great article! It cleared up a lot for me. Easy to read and understand. Thanks!

Thanks for the kind commend Raymond and I am so happy to hear that you found it useful. From my perspective, feeling comfortable with chord theory does a lot to increase your understanding of both the guitar and music in general, and I really hope that it’s helping your playing! 😁