In my opinion, learning how to connect the 5 pentatonic shapes across your fretboard is one of the best ways to improve your lead guitar playing. It will help you to improvise freely, to create interesting blues guitar solos and to navigate comfortably across the entire neck of your guitar.

Learning the connections between the 5 pentatonic shapes will allow you to break out of patterns and areas of your fretboard where you feel stuck. And this in turn will reduce the likelihood of your solos sounding repetitive and potentially uninteresting.

So if you feel confident playing the shapes of the minor pentatonic scale, but you yet don’t yet feel so confident using them in a practical context, then the information laid out here will do a lot to improve your confidence. In this article, I will cover:

- The structure of the minor pentatonic scale, and how you can use it to develop connections across the fretboard

- How to establish key areas of the fretboard that you can target in your solos without becoming overwhelmed by all of the different scale shapes

- How to move laterally between the 5 pentatonic shapes

- Fretboard connections that will help you to break out of patterns you find yourself repeating, and away from areas of the fretboard where you feel stuck

Before we look at the different ways that you can move between the 5 pentatonic shapes, I think it is worth noting a number of points. These are as follows:

The concepts covered in this article increase in difficulty. As such, if you are fairly new to playing blues lead guitar, then I would recommend going through them in order.

Start with the first concept and get comfortable with it, before moving on. The initial ideas outlined here only require you to know the shapes of the minor pentatonic scale. Conversely, those featured later in the article require you to have a slightly deeper understanding of your guitar’s fretboard.

Regardless of the level of your playing, take time to get to grips with these concepts. The minor pentatonic scale provides the foundation for blues lead guitar playing. It is a hugely important scale and it is one that you are likely to use extensively in your playing.

This is true, even if you go on to learn different scales and modes. As such, don’t rush through this material. It is much better to take your time to work through these ideas – but to grasp them fully – than it is to rush through them and fail to implement them effectively in your playing.

Finally, the material here is focused solely on the minor pentatonic scale. This is unquestionably the most popular scale amongst blues guitarists, and it is also typically the first scale that most players learn.

However the ideas outlined here also apply to both the blues scale and the major pentatonic scale too. So if you are using those scales in your playing, then the material outlined here will also help you to develop connections between those shapes.

With that in mind, let’s get into it! Here are some of the key ways you can connect the 5 pentatonic shapes across your fretboard:

Establish initial pentatonic connections

The first and easiest step that you can take to connect the 5 pentatonic shapes, is to get to grips with the following concepts:

There are 5 individual pentatonic shapes, which always appear in numerical order on the fretboard. These 5 pentatonic shapes repeat.

So once you have played the fifth shape in any given key, the next shape to appear on your fretboard will always be the first shape. After that you have the second shape, and then the third shape etc.

All of these pentatonic shapes overlap. They all connect with each other. And every shape of the pentatonic scale contains notes that are found in the other shapes of the pentatonic scale.

On their own, these observations might at first seem so obvious that they are barely worthy of mention. Yet in fact, fully understanding these ideas will go a long way in helping you to move around your fretboard. Let’s look at each of them in more detail:

Count by numbers

As you most likely already know – the shapes of the minor pentatonic scale always appear in numerical order on your fretboard. So once you have found shape 1 of the scale in any given key, the next shape along will be shape 2, and so on.

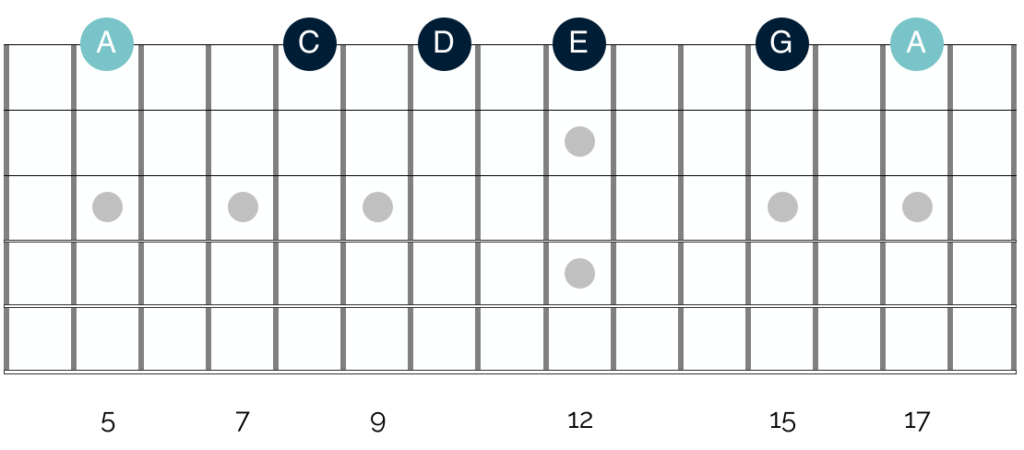

This concept is one with which I suspect you are already familiar. I do think it is worth reiterating though, that shapes 1-5 of the minor pentatonic scale do not cover your whole fretboard. In the key of A for example, position 1 of the scale starts on the 5th fret, and position 5 ends on the 17th fret.

At this point it is important to remember, that the numbers simply reset. So in the key of A, once you reach shape 5 of the minor pentatonic at the 17th fret, the next shape to appear on your fretboard is shape 1.

Conversely, shape 5 of the scale appears before shape 1 of the scale at the 5th fret. In the key of A then, both shape 5 and shape 1 of the minor pentatonic scale appear twice.

This repetition of shapes happens in every key. It is just that the specific scale shapes that repeat, change in different keys.

You don’t need to worry too much about playing in different keys for now. Instead, just focus on the idea that there are only 5 pentatonic shapes. And the numbers always run from 1 to 5. So once you reach shape 5, the next shape to appear on your fretboard will always be shape 1.

Conversely, shape 5 will always appear before shape 1 on your fretboard.

This concept might seem very obvious. Yet it will help you to know exactly where you are at any given point on the fretboard. This will help you to make connections between adjacent pentatonic shapes. And this is the first step to connecting all 5 pentatonic shapes with confidence.

Look for the overlap

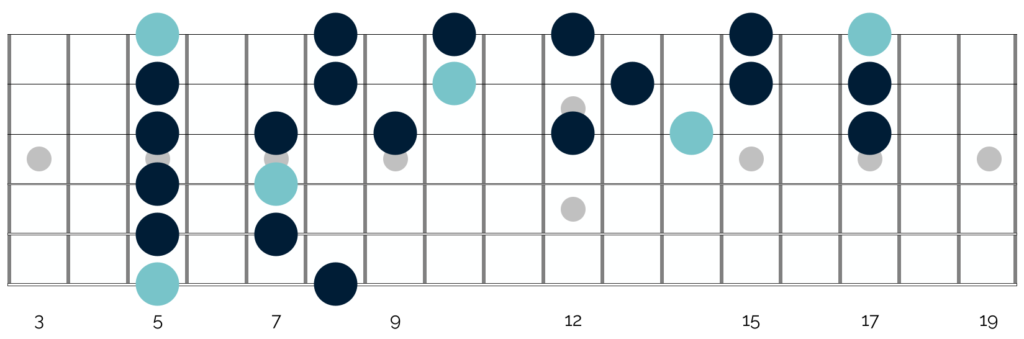

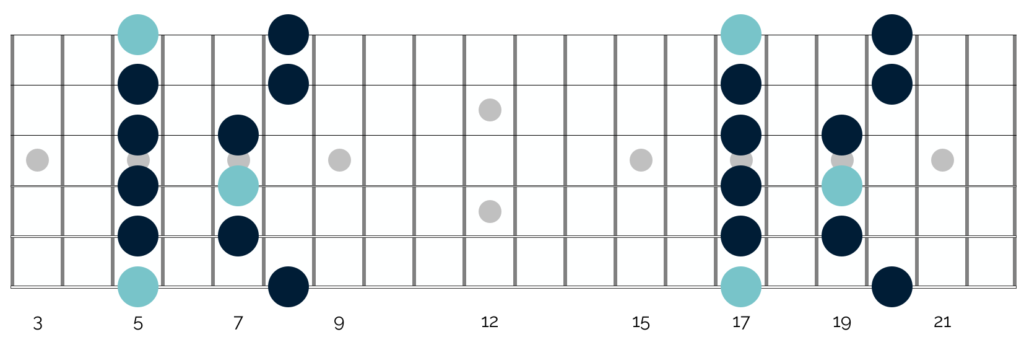

Once you feel comfortable with the order of the 5 pentatonic shapes, the next step is to establish the many points where these shapes overlap. Let’s look at the 5 pentatonic shapes laid out across the fretboard:

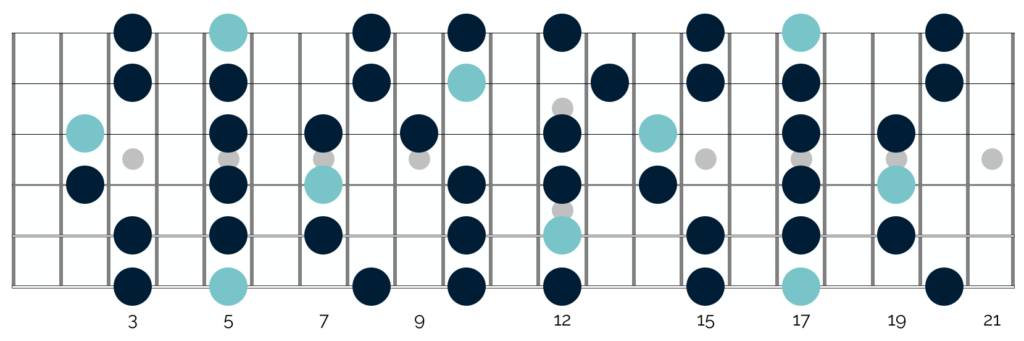

This diagram shows all of the positions of the A minor pentatonic scale. It shows all 5 pentatonic shapes, but actually shows 7 different positions of the scale. This is because, as noted above, the scale shapes are sequential.

So after reaching shape 5 of the scale at the 15th fret, you then play shape 1. Similarly, shape 5 appears at the 3rd fret, before shape 1 at the 5th fret. The light blue dots on this diagram show all of the notes of A that appear on the fretboard.

As you can see – the 5 pentatonic shapes are not separate. They are all connected and they all share notes with each other.

This has both positive and negative implications. The good news is that the pentatonic shapes you are trying to connect, are already connected. The bad news, is that there is so much crossover between the shapes and so many areas of potential connection, that it is difficult to know where to even begin.

The key to success here is to take one shape at a time, and establish a point of connection that works for you. Start with shape 1 and try to find the ways that it connects with shape 2.

Then move on to shape 2 and shape 3 etc. Don’t worry about all of the different ways the shapes connect. Instead find the one or two connecting points that work well for you.

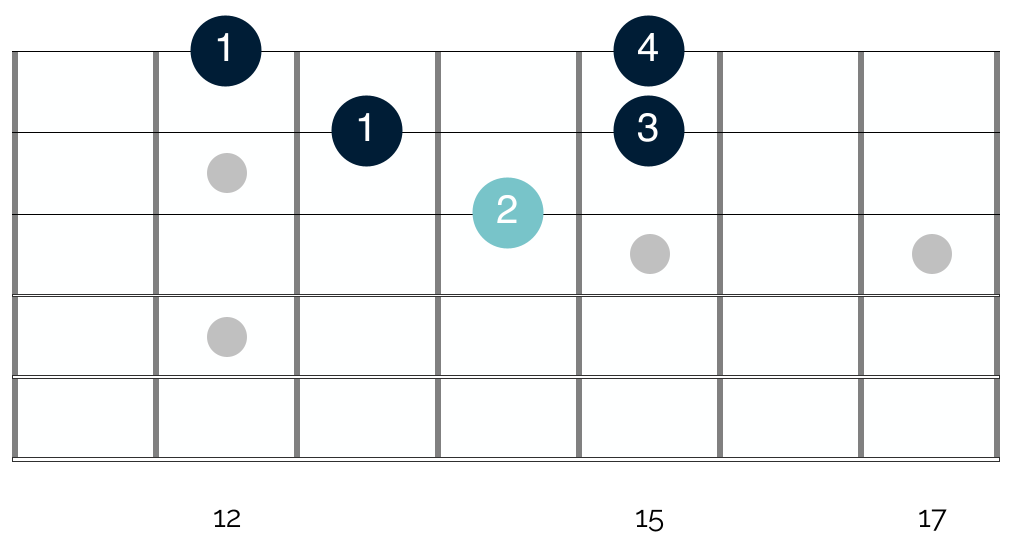

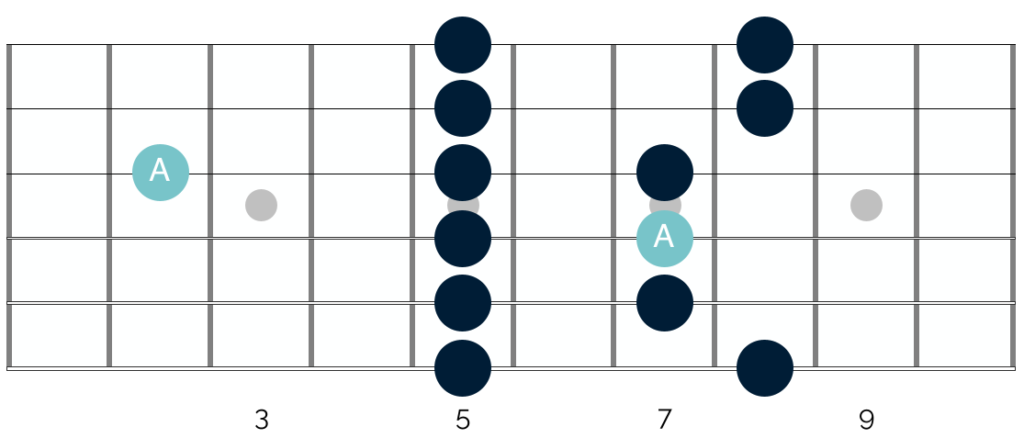

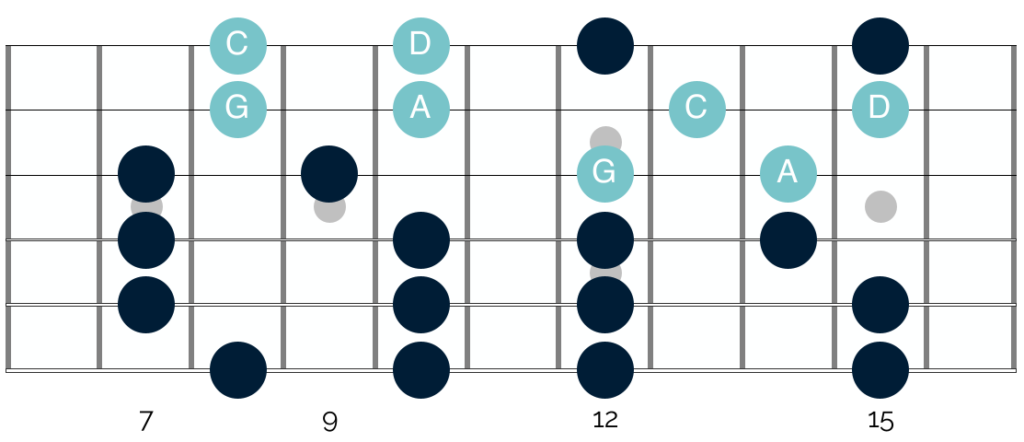

Let’s look at an example using just shapes 1 and 2 of the A minor pentatonic:

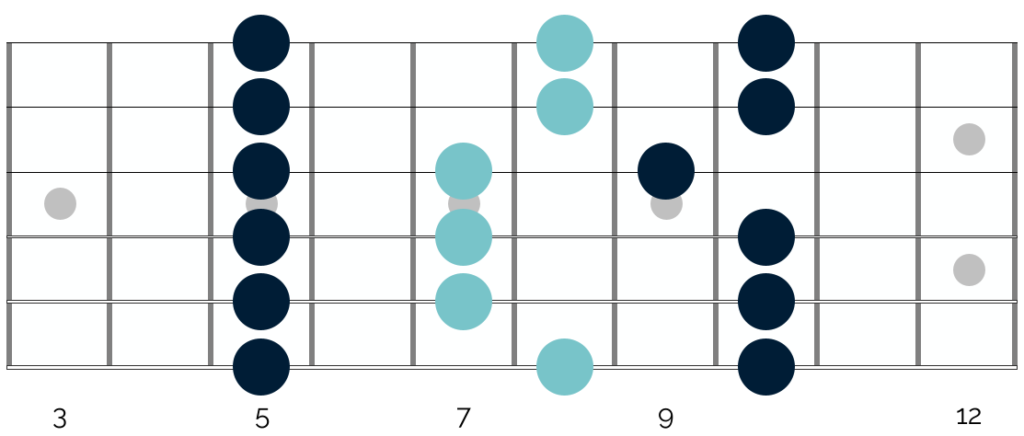

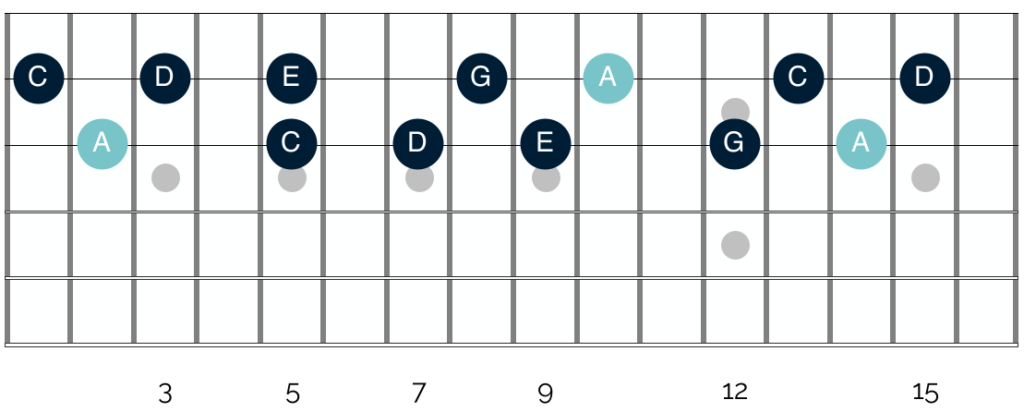

This diagram shows all of the notes that appear in shapes 1 and 2 of the A minor pentatonic scale. Unlike in the previous diagram, the light blue notes here don’t represent the notes of A. Rather they show all of the notes which are shared by both shapes of the scale.

As you can see, the 2 shapes overlap to such an extent that the notes on the right hand side of shape 1 are exactly the same as the notes on the left hand side of shape 2. In other words, there are connecting points at every step of both scale shapes.

As is true of the diagram above, there are arguably too many points of connection here to implement practically in your playing. So let’s break this down further and look at just a single point of connection:

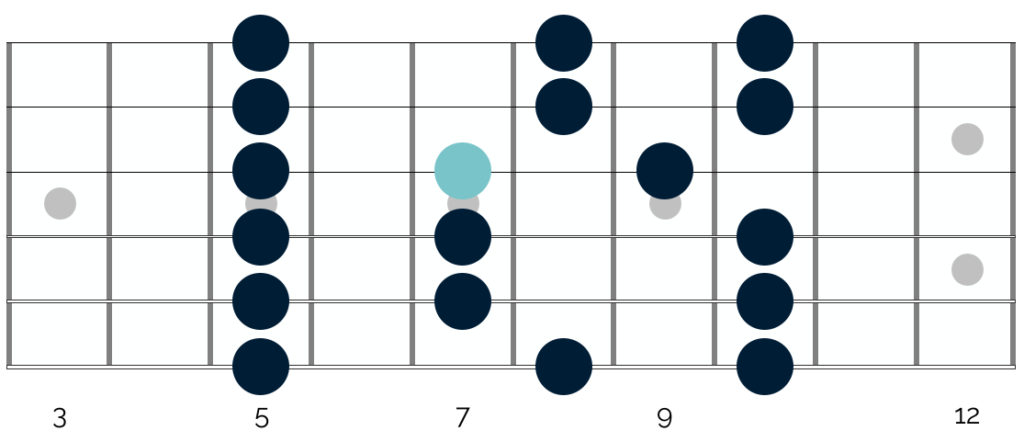

The note highlighted in light blue at the 7th fret of the G string makes a great point of connection between the 2 minor pentatonic shapes.

In shape 1 you play the note with your third finger. In shape 2, you play the same note with your first finger.

So, to switch between the shapes, all you need to do is alter your fretting hand position so that you switch the finger you use to play that note. And making this switch will allow you to create a variety of licks by moving quickly and seamlessly between the two shapes. Let’s look at a number of examples:

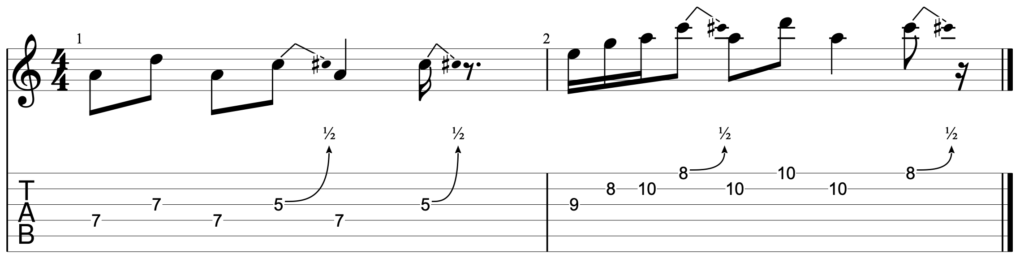

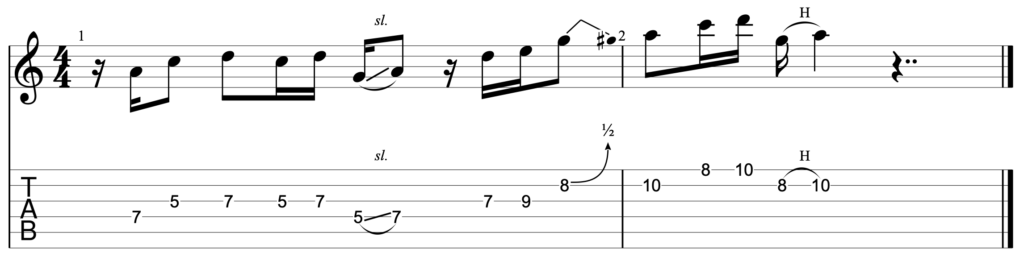

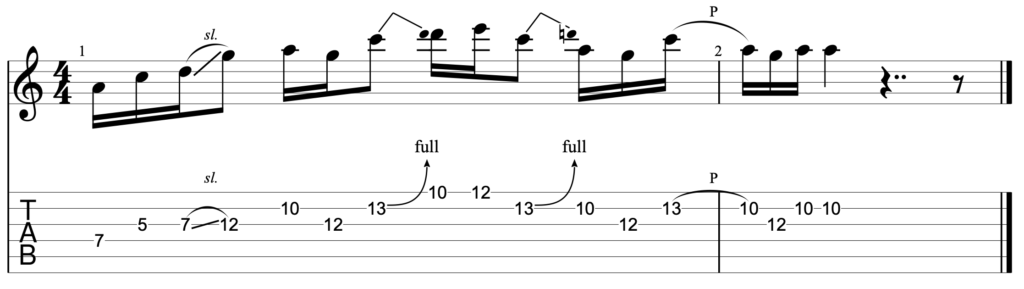

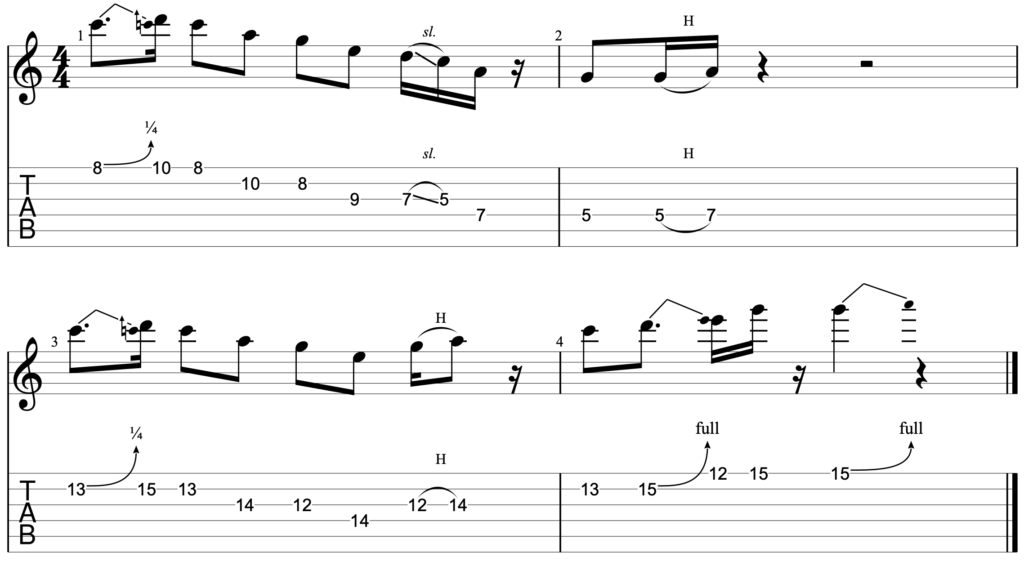

Lick 1

This is what this lick sounds like at 100 beats per minute (BPM):

Inspired heavily by Muddy Waters’ ‘Mannish Boy‘ – this simple lick shows how you can recreate similar ideas in both shape 1 and shape 2 of the minor pentatonic scale. All you need to do is move your fretting hand between the first and second bars.

I would recommend that you use your middle finger to play the 9th fret of the G string. This will allow you to easily play the notes in the second bar, and it will put you in a great position to move between the 2 pentatonic shapes.

Lick 2

This is what this lick sounds like at 100 BPM:

This lick highlights the ease with which you can move between these 2 pentatonic shapes. As noted above, all you need to do here is shift your fretting hand up 2 frets.

This allows you to play the 7th fret on the G string with your first finger. And it puts you in a comfortable position to play a variety of phrases in shape 2 of the minor pentatonic.

Lick 3

This is what this lick sounds like at 100 BPM:

This final lick presents a smoother and more musical way of shifting between the 2 pentatonic shapes. Rather than shifting between the shapes in between phrases, here you connect them as part of the lick.

Use your third finger to slide from the 7th to the 9th fret on the G string. When you do so, you will be in the perfect position to play a variety of phrases in the second pentatonic shape.

Limit your focus

In my experience, one of the biggest challenges that guitarists face when trying to connect the 5 pentatonic shapes, is battling a sense of overwhelm.

As you can see from the diagram above, when you lay all of the 5 pentatonic shapes out across your fretboard, you are presented with a huge range of different notes. If you then try to establish connections between all of those different notes, you are likely to struggle to know where to even begin.

As such, if these ideas are new to you, break the challenge down into smaller chunks. Don’t look at all of the different ways you can move between the 5 pentatonic shapes. Instead just start by looking at a couple of ways you can move between them.

Specifically, I would recommend looking at points on your G, B and E strings where the shapes connect. And there are two reasons for this:

Firstly, the notes on these strings form neat pentatonic boxes, which are fairly easy to remember and use when soloing.

Secondly, these are the strings that you are much more likely to use when you solo and improvise. Of course, that is not to say that your bass strings aren’t important. Rather it is to say that there is a greater likelihood that you will spend more of your time playing on your treble strings during a solo.

As a result of this, I recommend establishing different pentatonic box shapes on your top strings which you can use to create killer sounding blues licks.

This works particularly well for the shapes of the pentatonic scale in which you feel less comfortable. Let’s look at these different box shapes in a bit more detail:

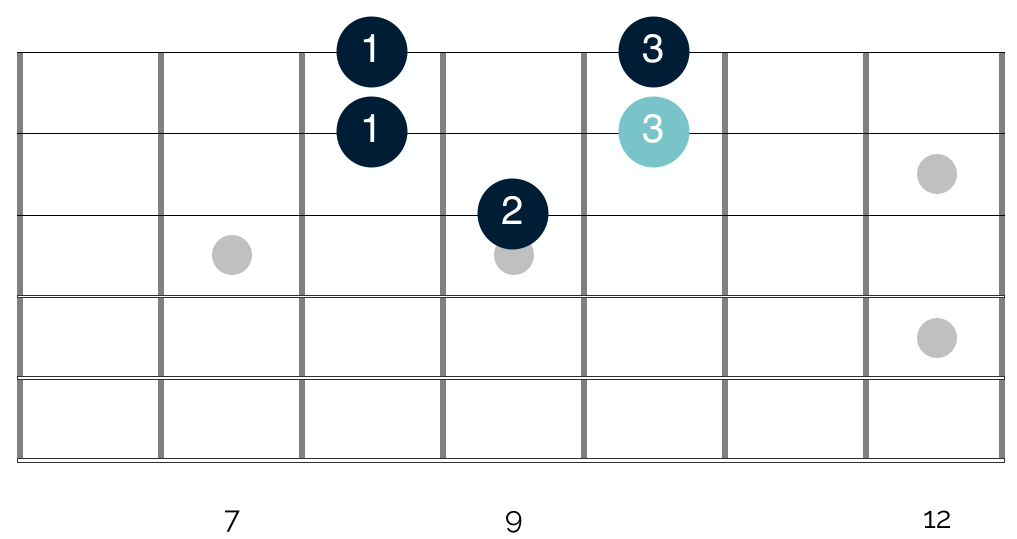

Pentatonic box – shape 2

The first pentatonic box that I recommend focusing on appears in shape 2 of the minor pentatonic scale. Albert King used this box shape to great effect, and it appears in a whole range of his most famous guitar solos.

B.B. King also used this box in place of his famous ‘B.B. King Box‘. He did this when playing in a minor blues context (where his major based B.B. King Box wouldn’t work so well).

This minor pentatonic box forms a very compact shape, which makes it both easy to play and to remember. Additionally, the shape lends itself well to string bending on the high E string, which sounds brilliant. The root note is at the 10th fret of the B string here. And this is a great note to play at the end of your phrases.

As illustrated above, you can connect this shape easily with the familiar and comfortable patterns from shape 1 of the minor pentatonic scale with which you may be familiar.

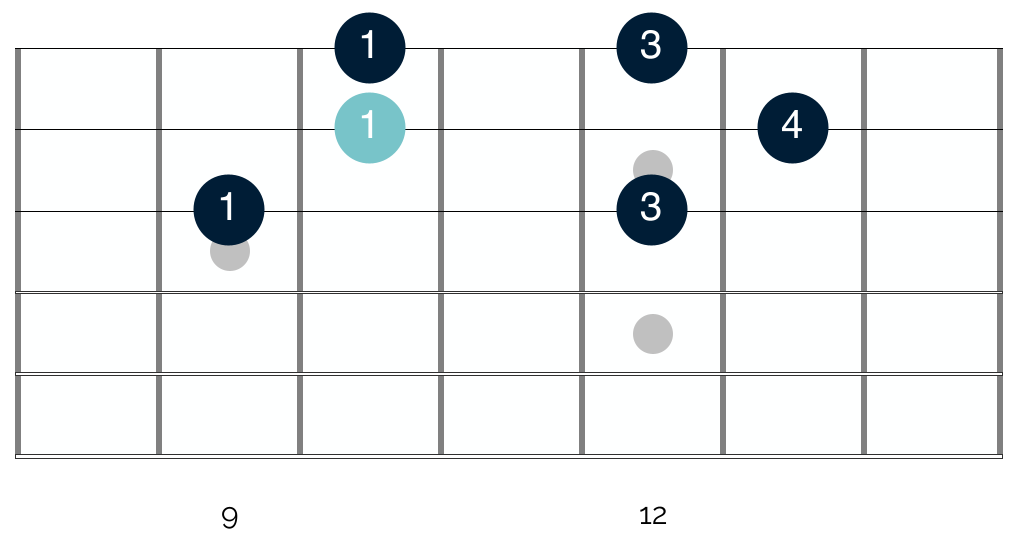

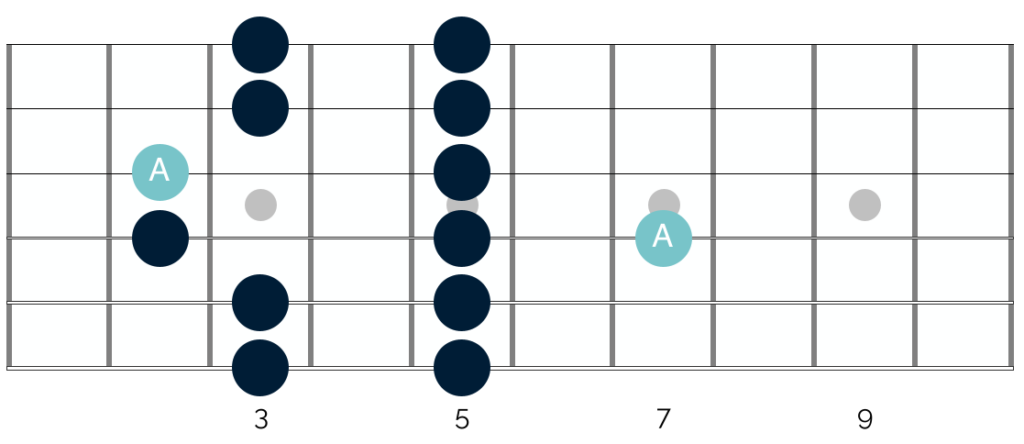

Pentatonic box – shape 3

The third shape of the minor pentatonic scale is one which I feel is often undeutilised. And whilst the full scale shape can be tricky to navigate, this is not true of the following box shape:

The shape is not as compact as the one listed above. Yet you can make it so by avoiding playing the note at the 9th fret on the G string. In this way you can focus on bending the 12th fret of the G string, and playing the notes on the B and E strings.

This shape lends itself well to slightly heavier techniques, like unison bends. As such, it is a shape that Eric Clapton favoured in his early playing. Having said that, it is suitable for more nuanced playing too.

Pentatonic box – shape 4

In my experience, the fourth shape of the minor pentatonic scale is the one that guitarists find most difficult to implement in their playing.

I think this is partly because it is asymmetrical, and partly because it is higher up on the fretboard, in an area where a lot of guitarists rarely venture. Again though, we can make the full scale shape easier to implement by just focusing on the top few strings:

As I will explain in more detail below, we can use further links on the fretboard to connect this shape with the box shape that appears in shape 2 of the minor pentatonic scale. And this allows you to move between the 2 shapes in a smooth and fluid way.

Pentatonic box – shape 5

Like the first shape of the minor pentatonic scale, shape 5 is symmetrical. As such, it is one that is typically quite easy to learn. This is especially true when compared with shapes 3 and 4.

However despite this, shape 5 does not lend itself so well to the comfortable and easy phrases that appear in shape 1. And so here as above, focusing on just a couple of strings can help:

When you first look at the shape, you might think it easier to use your fourth finger to play the 17th fret on the G string. And when practicing and playing scales, this is the finger I use to play that note. However here I have suggested using the third finger.

This is because in a practical playing context – and especially if you are playing at speed – I think it is easier to use this finger.

Connecting the boxes

You may have noticed that I have not added in a pentatonic box for shape 1 of the minor pentatonic scale. I have omitted it for two reasons:

Firstly, out of all the 5 pentatonic shapes, this is the one with which you are most likely to be familiar. As such, the likelihood is that you might already feel comfortable with this scale shape.

Additionally, of all of the pentatonic shapes, this first one forms the most comfortable patterns. And this in turn makes playing a variety of different licks and phrases easier than in the other pentatonic shapes.

The below diagram then shows each of the 4 pentatonic box shapes, in addition to the first shape of the A minor scale in full. The notes highlighted in light blue are the notes of A.

If you are struggling to connect the 5 pentatonic shapes, then try limiting your focus to these box shapes. It will help you to gain confidence navigating through them, without having to worry about all of your 6 strings.

Having said that, when laid out in full as above, you might still feel like this is too much to take on board. After all, there are still a lot of notes shown here, and all of these notes and shapes overlap with one another.

Don’t worry if that is the case. Break the challenge down into small chunks. Focus on each box shape at a time. Get comfortable playing them individually, and then work on trying to connect them. And when you do connect them, do so one at a time.

Don’t try to connect all 5 pentatonic shapes in one go. Instead, spend some time connecting shape 1 of the pentatonic scale with the first pentatonic box shape illustrated above. Once you are comfortable doing that, work on connecting the first box shape with the second.

Then connect these 2 shapes alongside the first shape of the pentatonic scale before you move on.

This slow and steady approach is what I would recommend when trying to get to grips with this material. And so at this stage, I would advise pausing to consolidate the ideas listed above. If you can implement them successfully, your playing will improve dramatically.

You can get a huge amount of mileage out of these concepts, so don’t feel the need to rush ahead. Take your time to grasp these ideas fully and use them confidently when you are soloing and improvising.

This won’t happen overnight, and so try to be patient before moving on. I say this partly to stop you from feeling overwhelmed. It is difficult to take a lot of information in and implement it effectively. And the risk is that you end up executing a lot of ideas poorly, as opposed to implementing one or two ideas very well.

I also suggest taking this approach, because effective blues guitar playing is all about nuance and subtlety. You don’t need to know a huge range of exotic scales.

Nor do you need to know all of the different and complex ways you can connect your 5 pentatonic shapes. Effective blues guitar playing is about expressing your emotions and making your listeners feel something through your playing.

Sometimes complexity can help here. But don’t underestimate the value of keeping things simple. Many of the most effective blues guitar solos of all time are based around simple patterns and movements. And yet they sound amazing.

So before you move onto some of the more advanced concepts listed below, spend some time implementing these initial ideas in your playing. Work on getting as much mileage out of them as possible. Once you have done so, you can turn your ideas to some of the slightly more advanced concepts below.

Move laterally between pentatonic shapes

The first of these more advanced concepts will help you to develop and get more from the connections listed above. It involves establishing a deeper understanding of your guitar fretboard and the logic behind how it functions.

I will cover that in more detail below. First though, I think it is worth pointing out the basic idea behind this concept.

Broadly speaking, I believe that guitarists think vertically, rather than laterally. In other words, they think about playing from their 6th string to their 1st string, and back again. And when they think about scale shapes and connections, they think in the same way.

This works well at first, but it can limit your playing, especially when you become more advanced.

The guitar is an interesting and hugely versatile instrument, precisely because it functions both vertically and laterally. This means that not only can you play scales vertically – from your 6th string to your 1st string – but you can also play them laterally, from the bottom to the top of your fretboard.

This might sound complex, but it makes a lot more sense when you see it laid out visually:

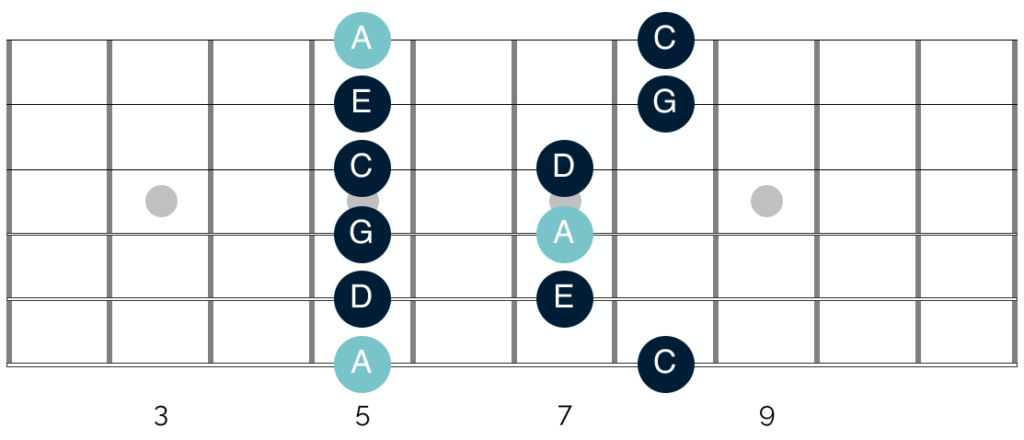

This diagram shows the notes present in what we know to be shape 1 of the A minor pentatonic scale. In technical terms, what this shows is 2 octaves of the A minor pentatonic scale, with a single additional note at the top of the scale. This additional note is the note of C and it is the second note of the minor pentatonic scale.

This is significant, as it shows the potential for lateral as well as vertical movement. Let’s examine this in more detail:

As above, this diagram shows the notes of the A minor pentatonic scale. Here though, it shows just 1 octave of the scale. It also shows the scale being played laterally across a single string, rather than vertically over multiple strings.

The minor pentatonic scale can be played laterally in this way across all of your guitar strings. We can see this by looking at the notes on the G and B strings:

This shows the notes from the A minor pentatonic scale, as they appear laterally across the fretboard. To save you from visual overload, I have presented this idea on just 2 strings, and in one specific section of the fretboard.

Yet this idea applies to all 6 strings and to the entirety of the fretboard. In other words, you can play the minor pentatonic scale laterally in multiple octaves across all 6 strings.

Connecting shapes laterally

There are two significant benefits in understanding how the 5 pentatonic shapes fit together laterally as well as vertically. These are as follows:

Firstly, and significantly, moving laterally across your fretboard allows you to connect the pentatonic shapes in a smooth and musical way. You don’t need to make big jumps between pentatonic shapes.

Instead, you can move between the 5 pentatonic shapes by targeting connecting notes on the same string. As you will see from the examples below, this helps you to move across your fretboard without sounding like you are simply shifting between different pentatonic shapes.

Additionally, focusing on lateral movement in this way helps you to add a very different feel to your solos. Specifically, it helps you to recreate the movements of a slide guitarist. Slide players predominantly move laterally, and in doing so, they solo in a way that is very different to ‘normal’ guitar players.

By targeting the same lateral movement in your solos, you can add this different feel to your improvisations.

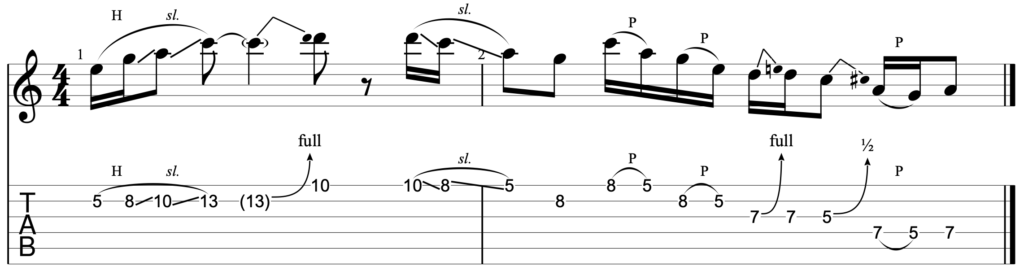

Let’s look at this in practice. Here are 3 example guitar licks that you can use to connect the 5 pentatonic shapes. All of these examples use the A minor pentatonic scale.

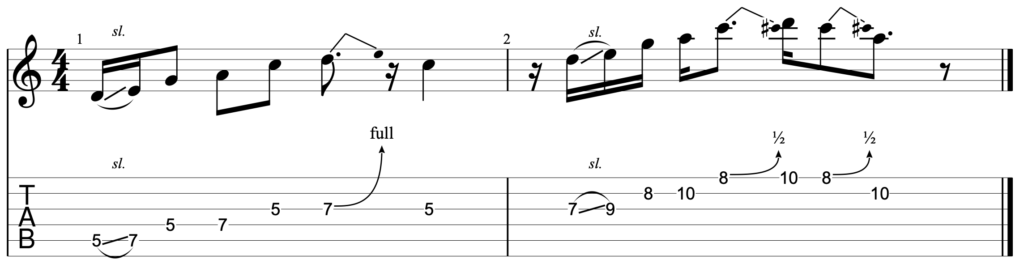

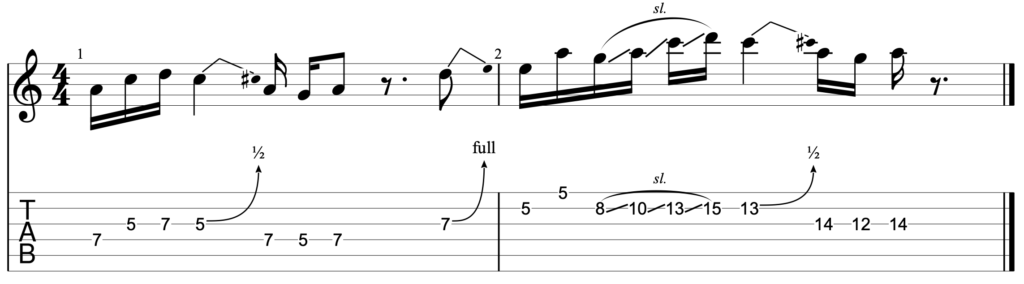

Lick 1

This is what this lick sounds like at 100 BPM:

The use of lateral movement in this first phrase is quite subtle. However despite this, it illustrates a very effective way that you can move between the first minor pentatonic shape and those higher up the neck.

Having the awareness of these movements will help you to incorporate additional pentatonic shapes into your playing, rather than getting ‘stuck’ in shapes 1 and 2.

Lick 2

This is what this lick sounds like at 100 BPM:

This lick extends the idea above. Here a slide on the B string is used to connect the second pentatonic shape with the fourth. And it does so in a way that is smooth and musical.

I would recommend sliding with your third finger here. This will give you control when you slide, and it will put your fretting hand in an appropriate position to play the final notes of the phrase.

Lick 3

This is what this lick sounds like at 100 BPM:

This final lick explores different forms of lateral movement between scale shapes. The phrase opens with an extended slide through shapes 1, 2 and 3 of the minor pentatonic. This slide settles on the 13th fret, which you then bend up. As such, I would recommend starting the slide at the 5th fret with your third finger.

Almost immediately, the phrase moves in the opposite direction. There is a quick slide down the E string – which this time is executed with the first finger. The phrase then resolves with a series of pull offs and bends in the first shape of the minor pentatonic.

Combine pentatonic patterns & fretboard connections

The last point that I am going to cover here, involves combining your knowledge of the 5 pentatonic shapes, alongside some broader fretboard connections. I cover many of the various different patterns that appear on your fretboard in much more detail in my article ‘5 Steps To Unlock Your Guitar Fretboard‘.

So if you are new to this material, I would recommend reading that, before continuing here.

In short though, there are a number of connections you can establish on your fretboard which will also help you to connect the 5 pentatonic shapes. Some of the most important of these are as follows:

One string up, five frets back

If you take any note on your E, A, D and B strings, you will find the same note at the same pitch on the next string up, 5 frets lower.

This relationship is not the same between the G and B strings. Your B string is tuned one half step lower than your other guitar strings.

And you need to account for this when you try to make connections from the G string to the B string. When moving from the G to the B string, you only need to move back 4, rather than 5 frets.

Let’s look at this connection on the fretboard. The diagram below shows connections between notes on the D and G strings:

This diagram shows the first shape of the A minor pentatonic scale. The note of A is highlighted at the 7th fret on the D string. And we can see that the exact same note appears on the G string at the 2nd fret.

This is significant for a number of reasons. Firstly, understanding this relationship will help you to move between the pentatonic shapes, as you can see below:

By targeting that single note, you can move from shape 1 to shape 5 of the pentatonic. And this helps for two further reasons:

Firstly, it helps you to shift to a new area of you fretboard. And this gives you access to all of the different notes in that area of your neck.

Secondly, it enables you to alter your licks to add a different feel to your playing. This is the case, even when you play exactly the same notes. Let’s look at this in practice:

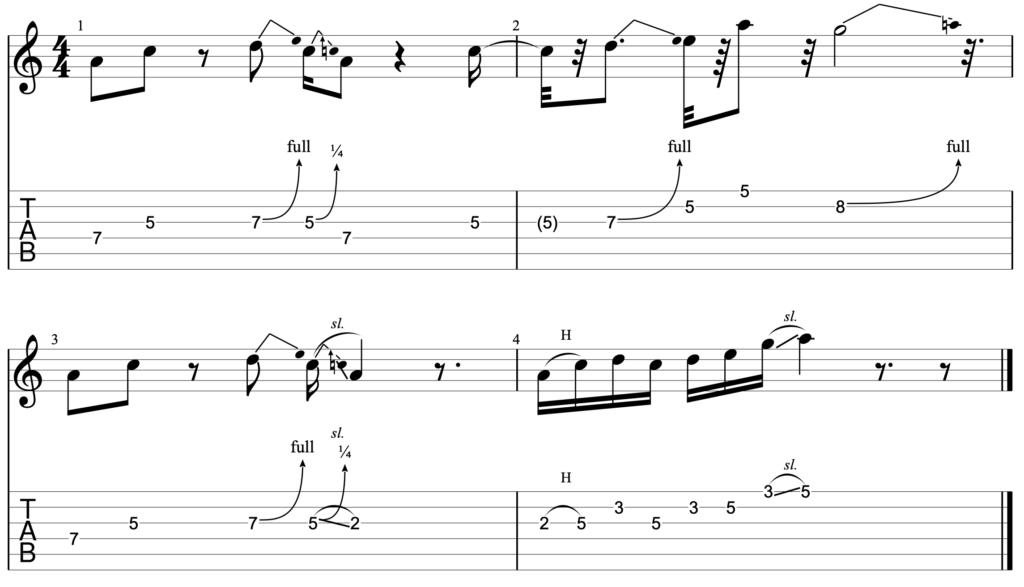

This is what this lick sounds like at 100 BPM:

The notes in bars 1 and 3 of this phrase are almost identical. The only difference is that in the first bar, you play the final note before the rest at the 7th fret of the D string.

Conversely, in the third bar you play that same note (the note of A) at the 2nd fret of the G string. Here you reach that note by sliding. So although the notes in these two bars are basically identical, the phrases are subtly different.

Perhaps more importantly though, shifting down to the 5th shape of the pentatonic alters the surrounding notes to which you have access.

This results in the 2nd and 4th bars of the phrase being markedly different from one another. It also illustrates how understanding these connections can help ‘unlock’ your fretboard, and result in better improvisations.

One string down, five frets up

It is worth noting that this relationship works the opposite way too. So if you take a note on one of the strings mentioned above and move down one string and up 5 frets, you will find the same note.

As you will see in the diagram below, this isn’t true between notes on the B and G strings. Here the difference is 4, rather than 5 frets.

Again, understanding this relationship will help you to connect the 5 pentatonic shapes and do so in a smooth and musical way.

It will also allow you to move to new areas of the fretboard and access the surrounding notes in that area to create a different feel. Let’s look at this in practice:

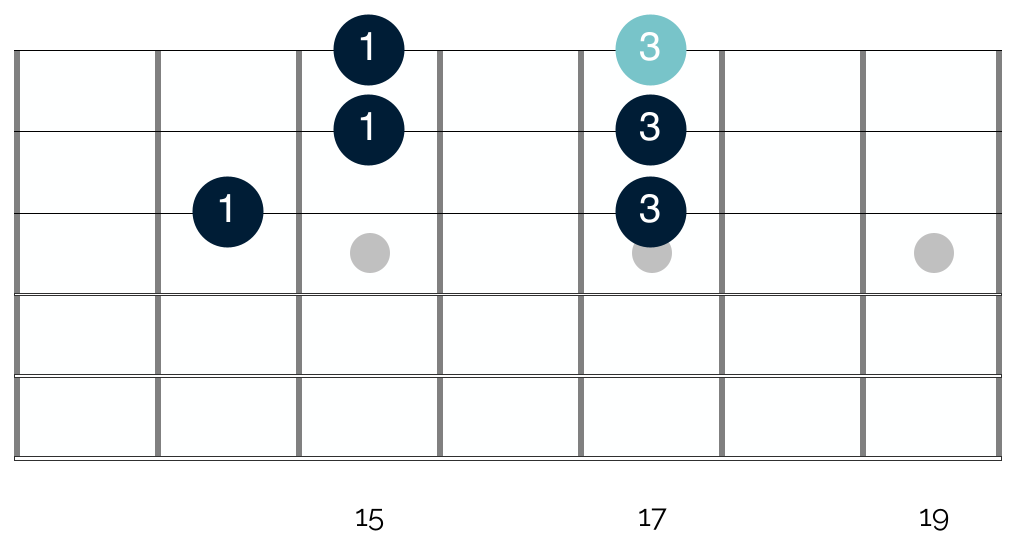

This diagram shows shapes 2 and 4 of the minor pentatonic scale. Shape 4 of the scale is one that tends to be under-utilised. It doesn’t form the nice easy shapes that you find in the some of the other shapes. And as a result, a lot of guitarists tend to avoid it.

Yet as you can see from the image above, you can find exactly the same notes in this shape, as you can in shape 2.

Knowing this allows you to switch to a new part of the fretboard in a smooth way. You can play the same notes as you do in perhaps a more familiar shape.

But now you have access to all of the different surrounding notes. And this allows you to create a wider variety of sounds in your solos and improvisations. Let’s look at this in practice:

This is what this lick sounds like at 100 BPM:

As above, the notes in bars 1 and 3 of this phrase are almost identical. The only real difference between them is that the notes in the first bar are played on the 8th and 10th fret of the high E string.

Conversely, those in the third bar are played on the 13th and 15th fret of the B string. The notes on both strings are the same pitch. As such, these 2 bars sound very similar.

However what bars 2 and 4 illustrate again, is that changing your position on the fretboard alters the surrounding notes to which you have access. Bar 2 focuses on notes in shape 1 of the minor pentatonic, whilst bar 4 focuses on notes in shape 4 of the pentatonic.

Knowing this connection allows you to move into areas of the fretboard where you might not feel so comfortable, and to reproduce phrases with which you are already familiar. It also allows you to cover large areas of the fretboard when soloing, without your playing sounding disjointed.

Same string, twelve frets up

The final fretboard pattern that will help you to connect the 5 pentatonic shapes, is as follows: If you take any note of any of your 6 strings, you will find the same note on the same string, 12 frets higher. This note is a whole octave above the original note.

This means that you can take any shape of the minor pentatonic scale, and find the same shape 12 frets higher. Let’s look at this in practice:

This shows shape 1 of the A minor pentatonic scale appearing twice; first at the 5th fret and then again 12 frets higher, at the 17th fret.

This relationship is the same for all 5 pentatonic shapes. The only key point to note is that because of the limits of your fretboard, not all 5 pentatonic shapes will appear twice in each key.

Most shapes will appear just once, with only 2 shapes repeating twice in this way in any given key. And the shapes that do appear twice will change, depending on the key in which you are playing.

Understanding this connection is useful because it allows you to take all of your effective phrases and licks and play them in a different register.

And this is a great way of increasing the intensity of your solos and improvisations. Understanding this relationship also helps you to unlock the upper frets of your guitar, which tends to be an area of your fretboard that is not so familiar.

My one piece of advice here would be to avoid simply jumping up a whole octave when soloing or improvising. This can work well when executed properly, but it can also make your playing sound quite disjointed.

Rather I would focus on moving up your fretboard using the various connections listed here. Then when you reach the same shape an octave higher, you can use the same licks and phrases you have been playing in the lower octave.

Putting it all together

One of the biggest temptations when learning new concepts like those listed here, is to rush through them. Arguably, this is particularly true of the minor pentatonic scale. So much of the educational material out there on this topic focuses on ‘breaking away from the minor pentatonic’.

Yet you should only do so once you are using the minor pentatonic scale effectively. And this is not as easy as it might sound.

For although learning the 5 pentatonic shapes might not be too challenging – using these shapes to create varied, interesting and impactful blues guitar solos is much more difficult. As such, I want to reiterate that it is worth taking your time with these ideas.

Work through them slowly and explore them as fully as possible. It is much better to take your time with each concept – but to really get to grips with it – than it is to rush through and fail to implement any of these ideas effectively.

My main piece of advice here – beyond following the ideas laid out here in order of difficulty – is to always break the challenge of learning these concepts into their smallest possible chunks. Don’t jump in and try to learn how to connect all 5 pentatonic shapes at once.

Instead, focus on connecting the first and second shape. Come up with licks and phrases you can use to join the two shapes. Once you feel comfortable doing so, try the same thing but with the second and third shape. Then try to join the first, second and third shapes together.

The approach here is one of adding additional layers of complexity to your playing over time. This means it takes longer to implement the ideas at first, but it greatly increases your chance of remembering them and utilising them effectively.

If you try to learn everything in one go, you will increase the likelihood of failing to implement any of these ideas effectively. So take your time, and you’ll be moving all over your fretboard and creating killer blues solos in no time.

Good luck! Let me know how you get on, and if you have any questions at all please do get in touch. Drop a note in the comments section, or send me an email on aidan@happybluesman.com. I’d love to help.

Responses

The licks do not play.

Thanks very much for letting me know Jim – I’ve just made a few changes and the licks should now be working again 😁 However if you do have any problems, or if I can help with anything else at all, please do let me know. You can leave a comment here or send me a message on aidan@happybluesman.com. Thanks again!

Absolutely Fantastic. That makes it a fair bit clearer for me .Thank you

Thanks so much for the kind words and for taking the time to comment David, I really appreciate it. Best of luck on getting to grips with moving between the different shapes. And if you ever have any questions – either about this topic or anything else I can help with – please do let me know. You can reach me on aidan@happybluesman.com and I am always around and happy to help 😁

I can’t believe you are providing this for free!! Absolutely brilliant approach and tips!

Wow – thank you so much for taking the time to write such a kind comment Diego, it made my day 😁 I am very glad to hear that you have found the articles helpful, and I hope you’re getting on well connecting the pentatonic shapes. If you do ever have any questions that I can help with though, just send them over to aidan@happybluesman.com. I am always around and happy to help!

Outstanding! Just what I was looking for. Thanks for this!

Thank you so much for taking the time to write such a kind comment Dennis. I really appreciate it and I am glad to hear you found the article helpful! 😁

Great stuff thank you so much Love it

My pleasure Mike and thank you for taking the time to write such a kind comment, I really appreciate it 😁

Great article for the intermediate player. For new players instead of learning five patterns, I find a good point of entry to be taking the box every 13-year-old player knows, moving it down to lower strings and playing octaves. You only need to remember the bend in the road at the B. So If your root is on the A string, you must shift two notes on the B. If You start on the D or G, you shift both the B and E positions. If you start on the B there is no change. By switching to the index finger at each octave, the most inexperienced player can play with confidence through three octaves. You will also see how those other patterns are derived.