Once you’ve nailed the standard 12 bar blues progression and are comfortable using dominant 7th chords, you should direct your attention to the minor blues.

For although blues is predominantly based around dominant chords, some of the most famous blues songs of all time are written in a minor key.

These include B.B. King’s ‘The Thrill is Gone‘, Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Black Magic Woman‘, and Albert King’s ‘As The Years Go Passing By‘, amongst countless others.

Compared to the regular 12 bar blues form, minor blues has a slightly different and darker feel to it.

It can be intense, powerful and emotionally charged. Understanding and learning its structure will expand your musical palette and make you a much better blues guitarist.

If you haven’t yet learned the ‘standard’ structure of the blues, then before you jump in here, I’d recommend properly getting to grips with that.

So if you are new to this material, start by reading these articles first:

Once you have that covered, you can dive straight in. So without further ado, here is everything you need to know about the minor blues.

The structure of the blues

The easiest way to understand the form of the minor blues is in relation to the regular 12 bar blues.

So it is worth a quick recap on how the 12 bar blues progression is structured and what gives it its ‘bluesy’ sound.

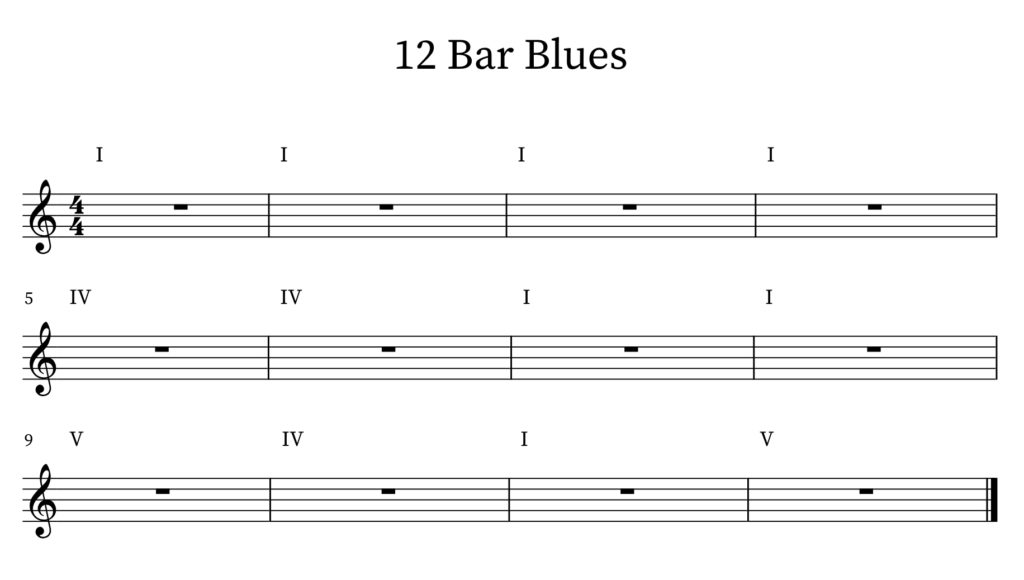

The standard 12 bar blues progression is constructed as follows:

The 12 bar blues is constructed using the I, IV and V chords in any given key. These chords are typically played as dominant 7th chords.

This is important, as it is the dominant 7th chords which give the progression its bluesy feel.

Dominant 7th chords contain all of the intervals found within a major chord – the root, major third and perfect fifth.

Crucially though, they also contain the addition of an extra note – the minor 7th.

This totally changes the sound of the chord. The minor 7th is a tone lower than the the octave.

This creates a harsh dissonance with the tonic note in the scale and gives the chord a tense and unresolved sound. It is this that makes dominant 7th chords perfect for the blues.

The minor blues form

You may then be thinking, what happens when we replace all of the dominant 7th chords in a 12 bar blues, with minor chords?

On a superficial level, not very much. You can simply switch all of the chords to their minor counterparts and play the 12 bar progression as normal.

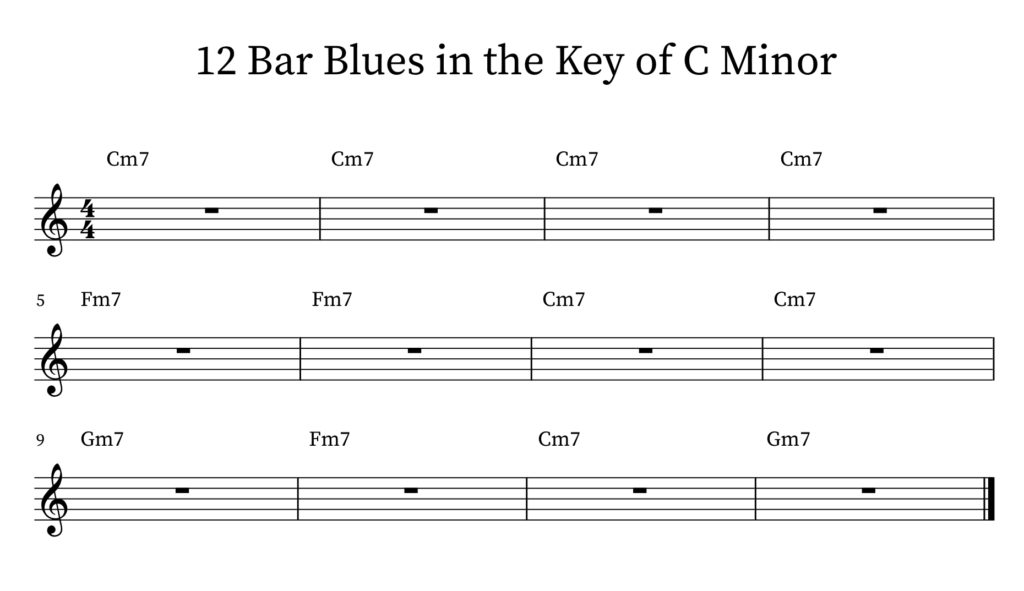

In the key of C minor, this would be as follows:

You may have noticed that the chords here are minor 7 chords, not straight minor chords.

This is because even when playing in a minor key, playing the chords as minor 7th chords creates a somewhat bluesier feel.

In theory then, you can play the minor blues by making this one simple alteration. Just turn the chords you play in a 12 bar blues into their minor counterparts and you’re good to go.

In practice, it isn’t quite so simple.

If you play through the progression above, you will find that it doesn’t sound quite right. Specifically, you’ll find that the last 4 bars don’t have the power and drive that you find in a typical and major 12 bar blues progression.

This is because in a typical and dominant based 12 bar blues progression, the V chord is quite dissonant. It creates a lot of musical tension, which seeks resolution.

This resolution is found when you return to the I chord. And it is this that makes the turnaround section of a 12 bar blues so effective.

Moving to the V chord creates tension and dissonance, which is then perfectly resolved when you move back to the I chord.

This doesn’t happen in this form of the minor blues. There isn’t the same dissonance within a minor 7th chord, because the minor 7th doesn’t clash with the major 3rd, as it does in a dominant 7th chord.

As a result, the turnaround section of a minor blues played exclusively with minor chords can fall a bit flat.

Common forms of the minor blues

To counter this, there are 3 common forms of the minor blues, the structure of which are all slightly different to the standard 12 bar blues progression.

I will run through each of these in detail, but first there is a bit of theory to cover.

As you might recall from my previous articles, when we refer to the structure of the 12 bar blues, we talk about the I, IV and V chords.

I will be talking about these again today, however there is one important distinction of which you need to be aware:

When writing chords in Roman numerals, major chords have capitalised numerals – I, IV and V etc. Conversely, minor chords have lower case numerals – i, iv and v etc.

So in a major blues, the one chord would be referred to as I. In a minor blues, it would be referred to as i.

In some of the examples below, the progressions mix minor and major chords, so just keep an eye out for this nuance.

Now, let’s have a look at the 3 most common forms of the minor blues:

Variation 1 – adding in the 7

The first form of the minor blues is nice and straightforward. This is because the structure of the progression remains almost unchanged when compared to a standard 12 bar blues.

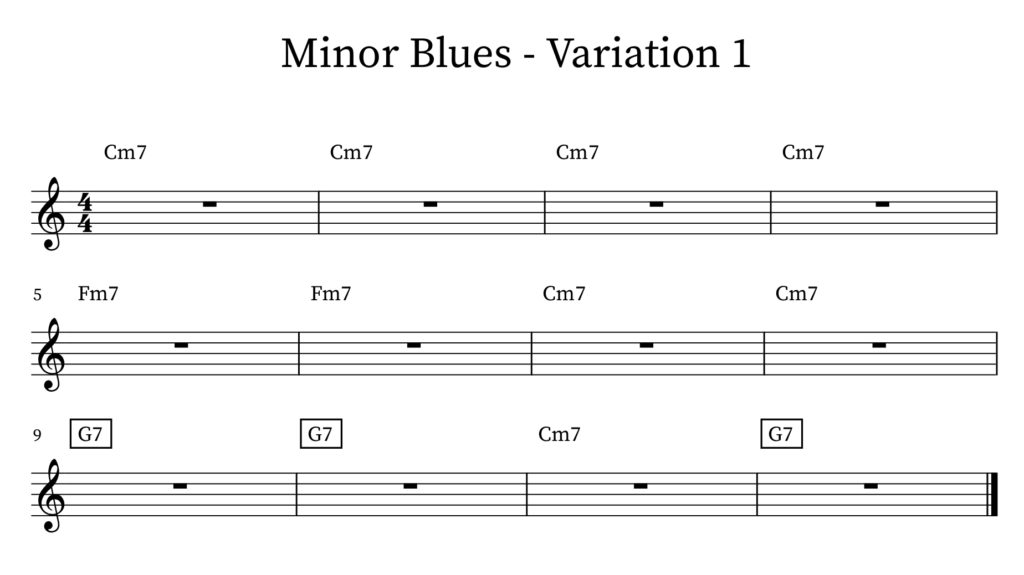

This is what this variation looks like in the key of C minor:

The key difference here is that the V chord is major. The whole progression is minor, until you get to the turnaround section of the progression.

At this point, instead of moving up to the Gm7, you switch to a G7 chord (as highlighted in the black rectangles above).

This creates the same tension that you find in a normal 12 bar blues and keeps the whole progression moving.

It does however require one further change to the normal 12 bar progression, which you may have already spotted. Typically in the final four bars of a 12 bar blues, the chords run as follows:

V IV I V

That doesn’t work here. This form of the minor blues works because you move from the dissonance of the V chord to the resolution of the i chord.

If you switch from the major 7th (V chord), to a minor 7th (iv chord) and then to a minor 7th (i chord), it doesn’t flow very well.

As a result, the iv chord is missed out altogether in the final four bars. In its place you play the V chord for 2 bars, before moving through the final 2 bars and then back to the beginning of the minor blues.

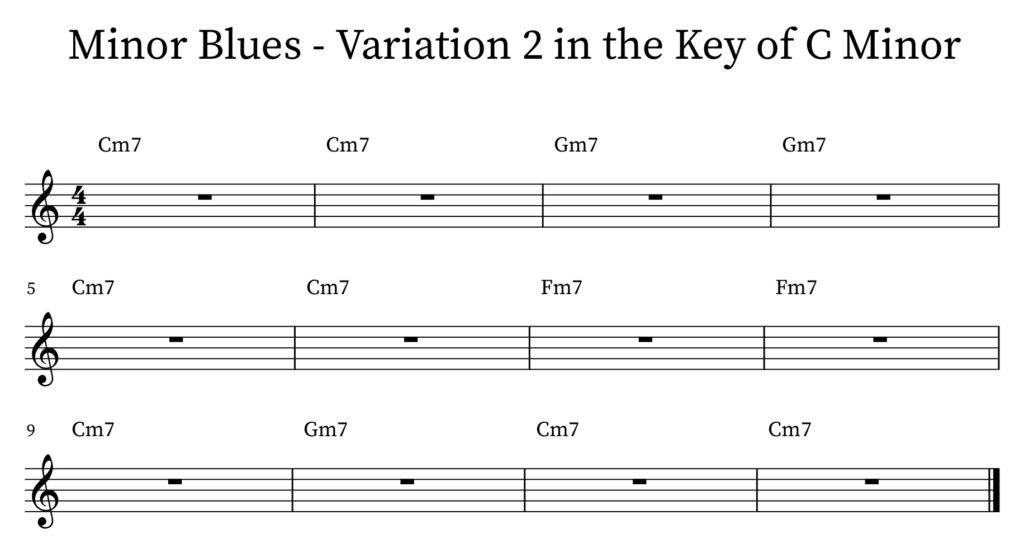

Variation 2 – altering the order

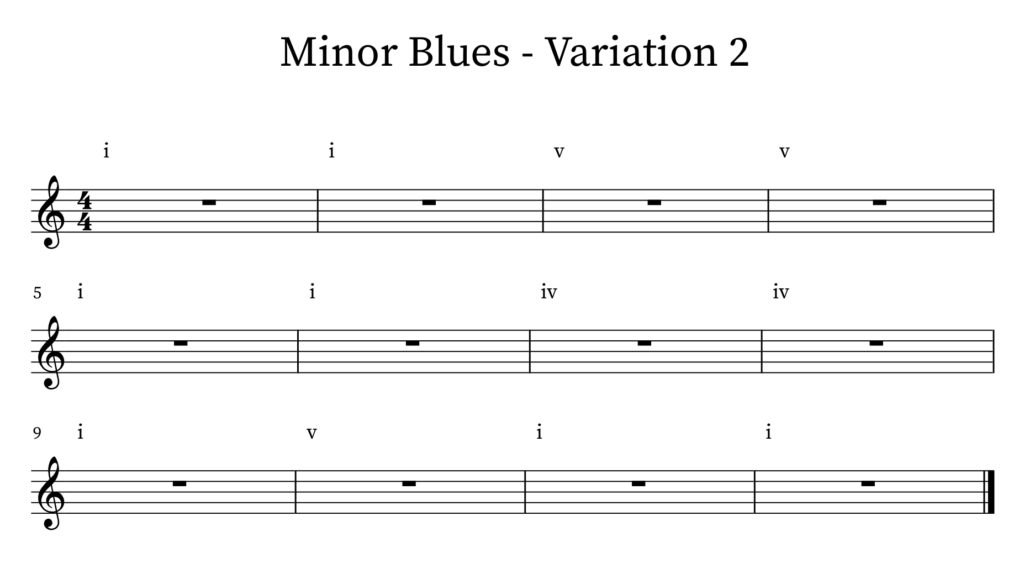

This second variation on the minor blues was used to great effect by Fleetwood Mac in their song ‘Black Magic Woman‘. It is a completely minor blues progression, and unlike the first variation, it doesn’t utilise any dominant chords.

Instead, the order of the chords is changed. This side steps the otherwise awkward transition from the v chord to the i chord.

Here then, the chord progression is as follows:

This is a very commonly occurring minor blues progression, and one that is definitely worth committing to memory.

So to bring it to life a bit, this is what this form of the minor blues looks like in the key of C minor:

Once you have this chord progression under your fingers, try shifting it up one whole tone, so it’s in the key of D minor.

You will then be playing the exact chords from Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Black Magic Woman‘.

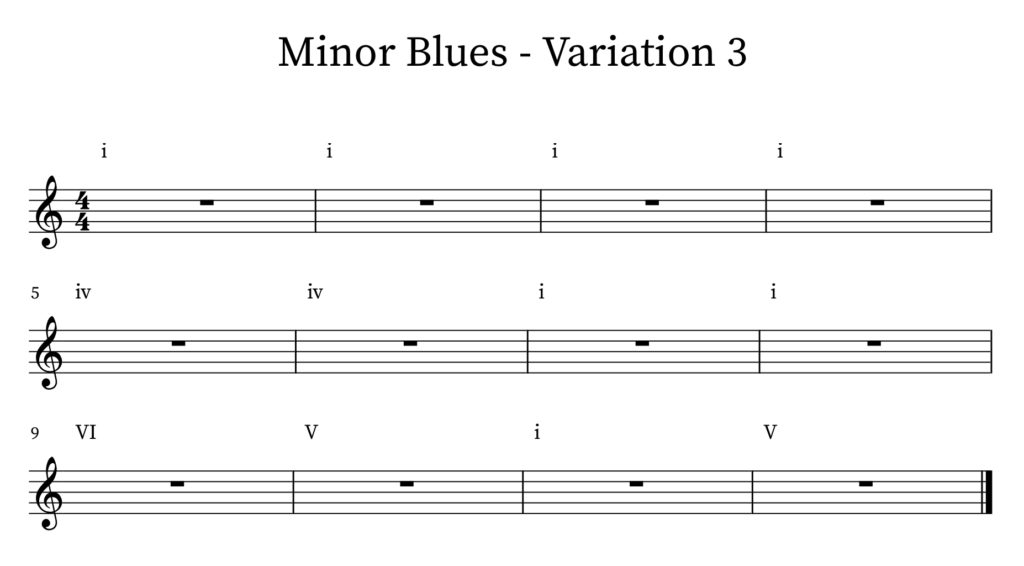

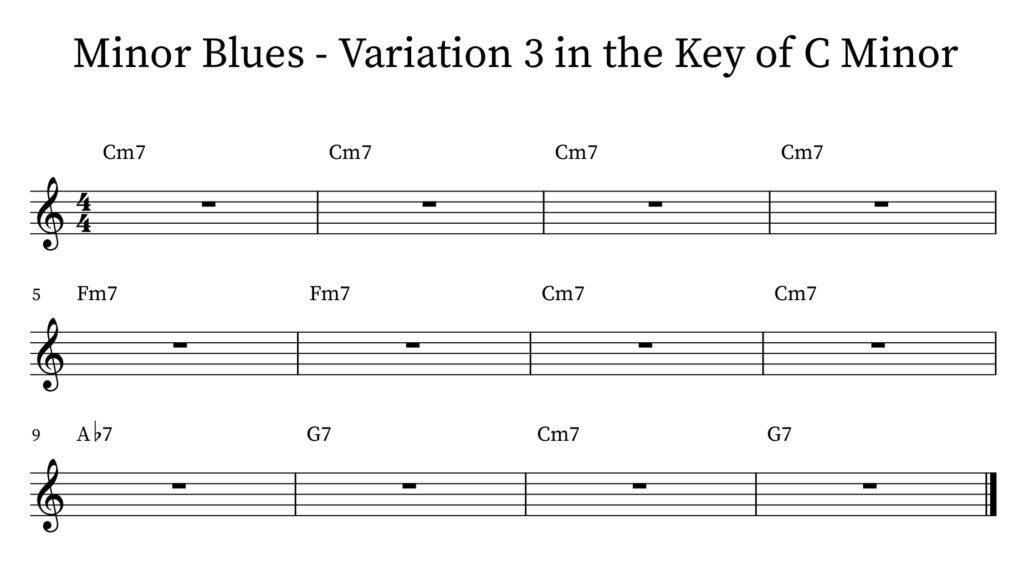

Variation 3 – adding the VI chord

The final form of the minor blues is the most complex of the 3 variations outlined here.

It alters the standard order of the 12 bar blues, mixes minor and major chords and also introduces additional chords outside of the I,IV and V.

It is a slight variation of this form that features in ‘The Thrill Is Gone‘ – one of B.B. King’s most famous songs. So like variation 2, this is a very commonly occurring chord progression and one you need to know.

This is what it looks like:

As you can see, the first 4 bars of the progression are exactly like those in a regular 12 bar blues. At bar 9 though, things change quite dramatically.

You move from the minor i chord, to the major VI chord, and then down to the major V chord before wrapping the progression up.

Sticking with the key of C minor, this is what this progression looks like:

Some closing thoughts

Well there we have it, some of the most common forms of the minor blues.

Within these forms, there are of course countless variations and far too many to include here.

As such, you can’t memorise just the one chord progression, as you may have done with the 12 bar blues.

Having the knowledge of the minor blues and an understanding of some of the most common forms of the minor blues will greatly improve your rhythm playing. It will also prepare you to jam with other musicians in a live setting.

So give these variations a go, let me know how you get on, and if you have any questions – just post them in the comments or send me an email on aidan@happybluesman.com. Good luck!

Images

Feature Image – Flickr (Public Domain)

References

Andy Le Maire, Guitar Master Class, Music Theory for Guitar, Edmprod, Premier Guitar, Youtube, Guitar Chords,

Responses

Thanks a lot for a such a clear, detailed enough(but not boring) explanation. As a hobby beginner that’s exactly what I was looking for!!! Many many thanks!

You’re very welcome Andrej – I am so glad that you found the article helpful and thank you for taking the time to comment, I really appreciate it. If you ever have any questions about your playing, or if there is anything else I can help with, then please do get in touch. You can reach me on here, or on aidan@happybluesman.com. I am always around and happy to help 😁

You mention the minor 7 is equivalent to the semitone below the octave. This is a whole tone or two semi tones below the octave.

Thanks very much for spotting the typo Isaac and for flagging it up! I’ve just updated it now 😁

Great explanation! Simple and complete. A slight variation I’ve come across is that 9th bar chord to be a maj7 chord. In your example the turnaround would be Abmaj7 / G7 / Cm7 / G7. Sounds awesome. Thanks!

Thank you so much for the comment and the kind words Manu, I really appreciate it.

Thank you also for adding that suggestion – it sounds great and I’ll definitely be adding that into the mix! Thanks again 😁

hi. great article! one question. in variation one, you mention adding a Gmaj7 chord but show G7 (dominant) in the music. it should be dominant, right?

It should indeed be G7 and not Gmaj7 – thank you for spotting the typo and for letting me know! 😁 Good luck with those minor blues progressions and if I can ever help with anything, please do let me know. You can reach me on aidan@happybluesman.com and I am always around and happy to help!

Hi I am a bit confused with variation 3 you used an Aflat7, I thought that the chord built on the six degree of the scale should be a major and not dominant, should it not be Abmaj 7 chord, or am i missing something thank you in advance. Best Regards, Alain

I enjoyed your basic description of minor blues. Thanks. Two comments: 1) I assume most minor blues are not syncopated, ie. they are played straight time, and 2) are played at a slower tempo than most major blues.