I have a confession to make.

For some reason I decided to record the videos for this mini course at the very end of an 8 hour day in the studio. I had been playing for at least 6 of those hours – working on solos and improvisations.

Why I decided to record Tightrope last – one of the fastest and most frenetic solos of the day – remains somewhat of a mystery to me.

When it came to recording Tightrope, I managed to get through the actual solo in tact. This however, was not true for the improvisation.

I tried to recreate a blistering SRV style solo, full of intensity and aggressive blues licks executed at speed.

Unfortunately, my fingers had other ideas. They were shot to pieces and I just couldn’t play the ideas I had in my head.

At first, I thought all was lost. I was working out how and when I could reshoot the material and get the solo nailed.

Then it dawned upon me. My torched fingers failing on me was not a curse, but rather a blessing.

This might sound confusing, but let me explain why in a bit more detail:

Many of the guitarists that I coach on a 1-2-1 basis want to play and sound like Stevie Ray Vaughan.

This is brilliant. However, for those earlier in their playing journey – speed and technique almost always prove to be a significant hurdle preventing them from learning Vaughan’s material and improvising in his style.

This is because almost without exception, Vaughan’s songs contain fast licks. This is true also for Tightrope, which as you have already seen from the previous lesson, contains a very fast solo.

This then begs the question, how can you add a bit of SRV magic to your playing right now – even if you don’t quite have the technique to execute some of the faster elements of his playing.

Riding with the King

The answer – play like Albert King.

Along with Jimi Hendrix, Albert King was unquestionably Vaughan’s biggest musical influence.

In fact, detractors of Stevie Ray Vaughan often state that Vaughan’s approach is just to take Albert King licks and play them at speed.

Whilst I don’t believe this criticism is fair, King’s influence on Vaughan’s playing is unquestionable.

This provides us with a wonderful opportunity when it comes to improvising in the style of Vaughan. If you are not yet at the point where you can play at Vaughan’s speed, then you can improvise largely in the style of Albert King.

By then adding in a few choice SRV licks, you can create an improvisation very much in the style of Stevie Ray Vaughan, without having to play at your technical limit.

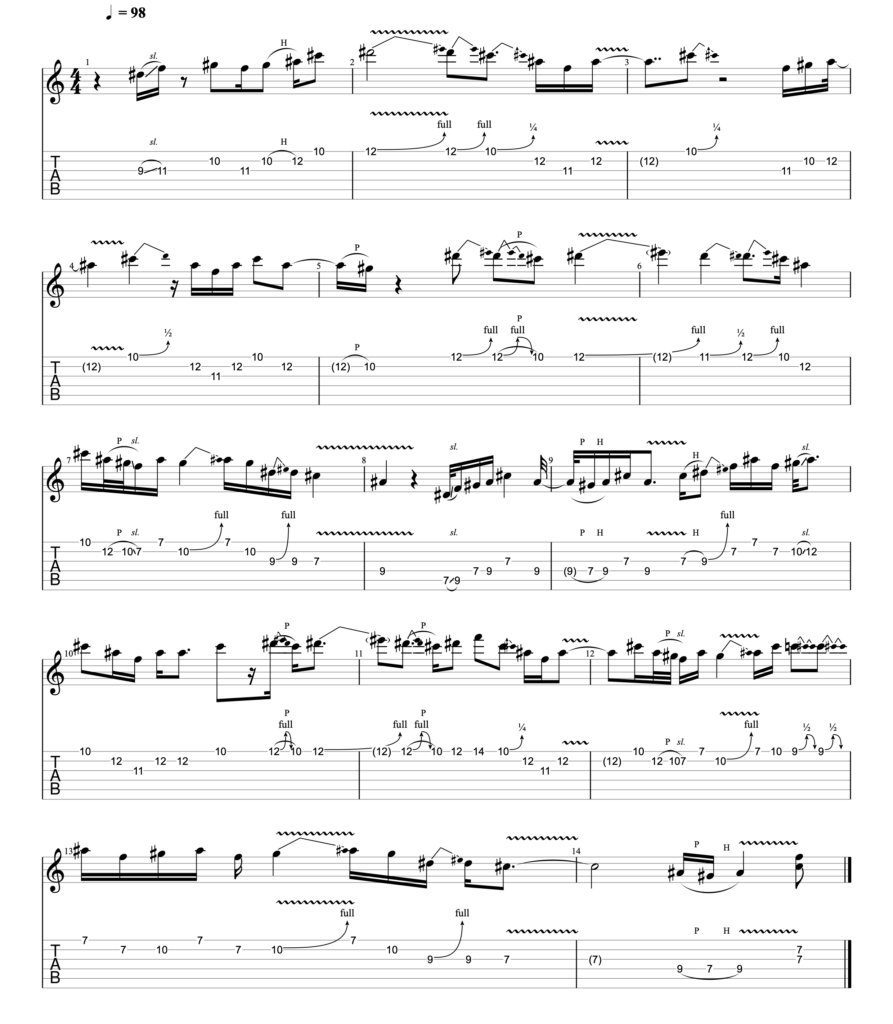

This is the approach that I take in the improvisation above, when I play the following:

In Eb tuning and at the 98 BPM at which the song is played, this is how the clean and isolated guitar part for this improvisation sounds:

Now then, let’s turn our attention to how I approached this improvisation and the stylistic elements of both Albert King and Stevie Ray Vaughan which I included in my playing.

The Albert King Box

I have written at length about the Albert King Box in various different lessons inside The Blues Club. I won’t repeat all of that material here. However if you would like a complete overview of the box, I would recommend working through this lesson in more detail – The Albert King Box.

In short though and as the name suggests – the Albert King Box is a compact bundle of notes that King used extensively in his playing. Just some of the many songs in which you can hear him solo using the box are as follows:

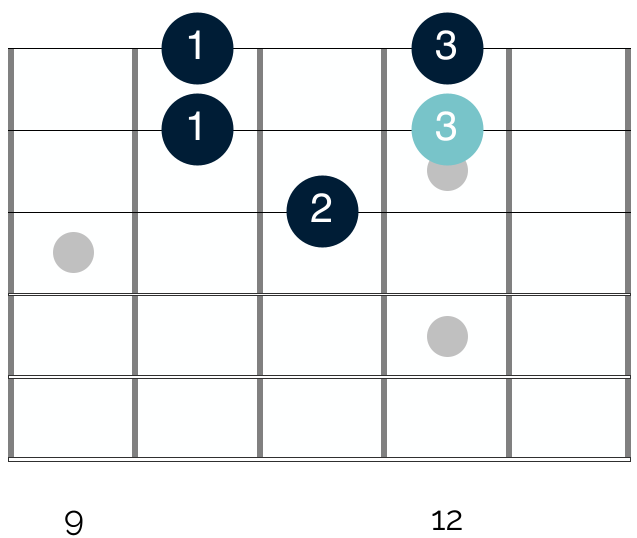

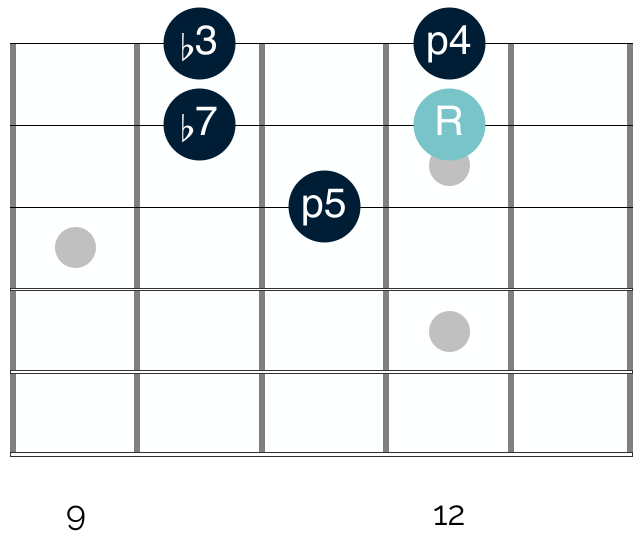

The box is in fact nothing more than 5 notes from the top of the second shape of the minor pentatonic scale. In the key of B for example – the Albert King box appears on the fretboard as follows:

I have highlighted the tonic note of B in blue, and shown the suggested fingerings I recommend when playing in the shape.

I suggest using these because they allow you to target the notes of the box with your strongest fingers. This is important as it allows you to bend and solo in the box more freely.

It is worth noting that in Tightrope, Vaughan tunes down to Eb, and I do the same throughout this course.

Technically then, we are both playing in Bb and not in B. However as in previous lessons of this mini course, I will talk here as if we are playing in standard tuning.

This is because when guitarists like Vaughan tune down to Eb, they are not altering the positions in which they are playing. In Tightrope for example, Vaughan is playing and moving across the B minor pentatonic scale shapes.

What we hear are the notes of the Bb minor pentatonic scale, but what Vaughan is playing on the fretboard – and what I am talking through in this lesson – are the notes of the B minor pentatonic scale.

The Albert King Box is so named because it appears with such frequency in King’s playing. However as noted above, it is in fact nothing more than the top 5 notes of the second shape of the minor pentatonic scale.

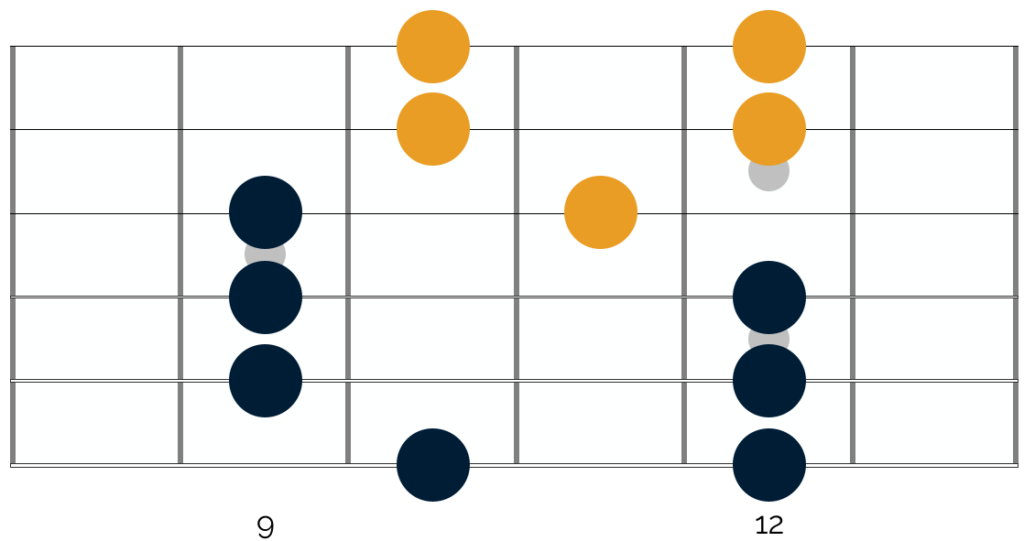

You can see this on the following diagram, where I have highlighted the notes of the Albert King Box in yellow:

In this way, you can see that the Albert King Box is not a new concept, but rather a bundle of notes from the pentatonic scale that you can target intentionally.

Using the Albert King Box

The Albert King Box is highly effective for a variety of different reasons – all of which I outline in detail in this lesson here.

In short though it works so effectively to include in your playing for the following 3 reasons:

1.) It is highly compact. In this way you can create a wide range of ideas in a small area of the fretboard

2.) It lends itself very well to bending. You can craft a whole range of different bends in the box; helping you to target notes from the minor pentatonic, major pentatonic and blues scales

3.)The box shape lends itself to certain licks and points of resolution, which have become synonymous with the playing of Albert King and Stevie Ray Vaughan

If you are new to the Albert King Box, then I would recommend first reading the lesson linked above in more detail.

Getting comfortable with the box shape is a fundamental step that will:

- Broaden your blues guitar vocabulary and build your confidence in this particular section of the minor pentatonic scale

- Help you to recreate the sound and feel of Albert King’s playing in your solos

- Provide you with a platform on which you can target specific ideas that Stevie Ray Vaughan uses in his playing

Once you feel comfortable navigating across the box and creating a variety of licks, you can look at ways to add more life to your licks, create a Stevie Ray Vaughan vibe in your playing, and place the box shape within a broader solo framework.

Let’s look at each of these points in turn:

Phrase capping

Before we look at some of the specific ways that Vaughan adds his own twist to the Albert King Box, I want to cover one of the easiest ways you can get more from this box shape.

This is through what is known as phrase capping.

If you are new to this idea, it simply refers to the way that you finish or ‘cap’ a lick or phrase. This is a key element of lead blues guitar playing, where it is typical to leave some space between phrases, most of the time.

As you might expect, there are a variety of different ways you can ‘cap’ a phrase. The most common of these is to target the intervals in the minor pentatonic scale which have the strongest sense of resolution.

To go into intervals and their qualities in depth is beyond the scope of this lesson. If you would like to learn more I would recommend heading over to the full course inside The Blues Club – An Introduction To Intervals.

In short though, intervals describe the distance between different notes. They also have different qualities, and can sound resolved, tense, warm and upbeat or melancholic and downbeat.

In the minor pentatonic scale in which we are playing here, there are 5 notes and therefore intervals, which are as follows:

1 b3 4 5 b7

If you don’t know what these numbers refer to then don’t worry; you don’t need to know all of the theory at this point to be able to target different intervals in your playing.

In short, the 1 (also referred to as the tonic or root note) has a very strong sense of resolution. If you play that note in your solo, it will sound totally resolved and will be lacking in any musical tension.

The same applies for the 5, which also has a very strong sense of consonance and resolution, though not quite as strong as the 1.

By comparison – the b3, 4th and b7 all have a less stable and therefore more tense sound.

As a result of their stable and consonant sound, the 1 and 5 are the obvious notes to target to cap your phrases. They sound resolved and as a result, sound like natural resting points for your phrases.

You can think of these intervals as the musical equivalents of a full stop. They create a sound of finality and when you target them at the end of your phrases, they bring a solid and clear structure to your phrases.

If in doubt then, targeting the tonic and 5th both make safe choices when soloing.

As you might imagine however, continually resolving to these notes can become a little predictable and repetitive. It also gives every single one of your phrases a strong sense of finality.

This isn’t a bad thing, but it can disrupt the sound of your playing, as none of your ideas are being connected together.

Fortunately, the Albert King Box provides you with wonderful opportunities to try capping your phrases in different ways. Let’s return to look at the box, but now with the intervals highlighted:

As you can see, all of the 5 intervals of the minor pentatonic scale are contained within the box. This – combined with the fact that the box is so compact – allows you to practice phrase capping on different notes.

You can see this at the beginning of my improvisation on the video and tabs above, where I cap my phrases on the b7 and b3, respectively.

As I do so, I play the notes briefly before cutting them off. This creates a brief moment of tension (where the note is played) before it is then cut off, and the tension resolved.

If you want to bring a little more variety to your playing and make it less predictable, try this out. Instead of always resolving on the tonic and 5th, try to cap your phrases on some of the less obvious notes in the box.

Playing the notes briefly and cutting them off as I have done can work very well, as it allows you to create tension without that tension getting out of control.

It is however, just one option. Experiment with a variety of different ways of playing these notes at the end of your phrases until you find what works best for you.

Bend stacking

Once you have experimented with phrase capping, you can turn your attention to a few further ways of playing in the Albert King Box. These are ideas that Stevie Ray Vaughan used a lot in his playing and as such, will help you to add a bit of that SRV magic to your improvisations.

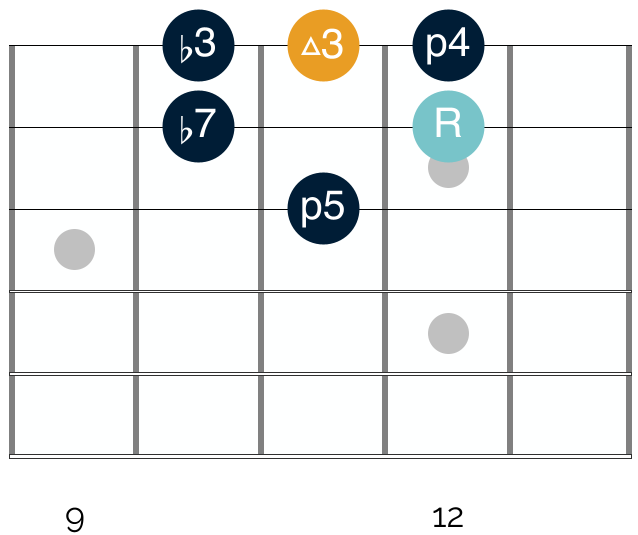

The first of these is to add an extra note into the Albert King Box. So instead of being a 5 note box shape, it now becomes 6, as follows:

As in the previous diagram, this shows the intervals present in the Albert King Box. Highlighted in yellow is the new interval that we have added into the box.

This is a major 3rd interval, which is not present in the minor pentatonic scale, but rather the major pentatonic scale.

A lot of lead blues guitar is based around the mixing of the minor and major pentatonic scales. The former defines the sound of the blues, whilst the latter allows players to add a warmer and more upbeat sound to their solos.

If you are new to the major pentatonic scale, then I cover what it is and how to use it in depth in these two courses here:

In the Albert King Box, the addition of this single note allows you to execute what I call ‘bend stacking’. This is where you move across the 3 notes that appear on the E string in consecutive order; targeting them with bends and stacking these bends together.

This allows you to create fluid and expressive blues licks that also move between the minor and major pentatonic scales.

I execute a condensed version of this idea around the 15 second mark in the improvisation above when I move between the 11th and 12th frets on the E string – targeting them both with bends.

In my opinion, bend stacking is so effective for 3 reasons:

- It helps you to get a lot of mileage from a small section of the fretboard

- You can use bend stacking to build tension and momentum in your solos

- It will help you to add a bit of that SRV magic to your improvisations

This last point is true, because this is often how Vaughan targeted the Albert King Box. Just one great example of this appear in the main solo in Texas Flood.

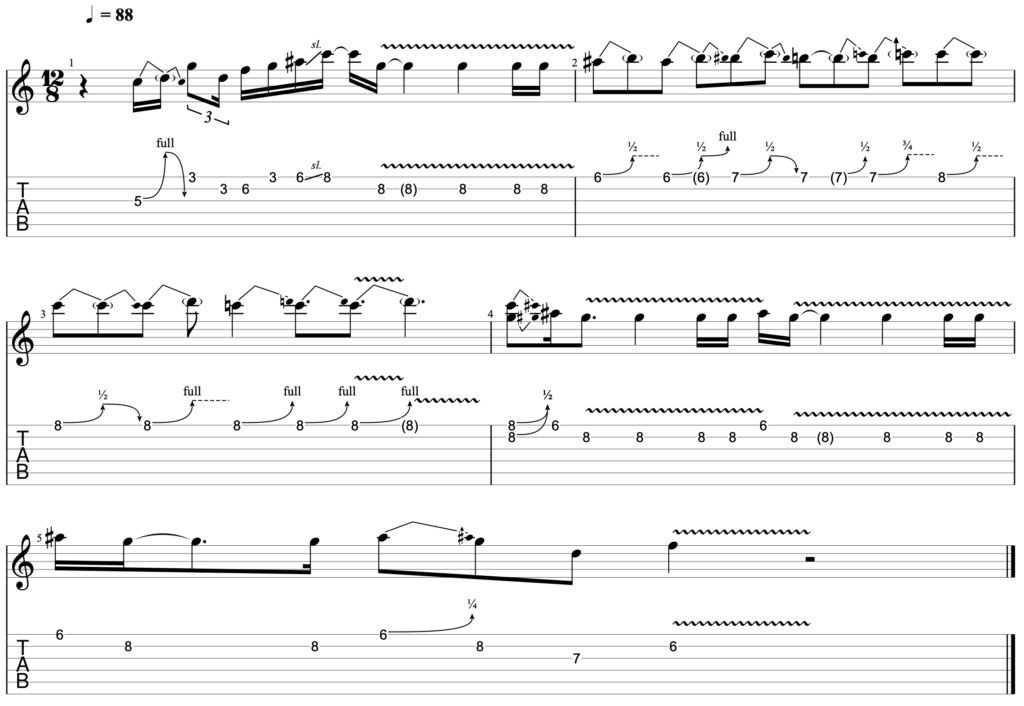

The solo starts around the 2.40 minute mark, and at around the 3.15 minute mark, Vaughan plays the following idea:

Vaughan plays the original song with his guitar tuned down to Eb, but uses the G minor and major pentatonic scales.

This is how this section sounds at 88 BPM (with the audio in this case adjusted to be in standard tuning):

As you can see and hear in the second bar of this clip, Vaughan uses bend stacking to build momentum in the solo.

He starts on the 6th fret of the E string and targets the note with two different bends. He then moves to the 7th fret – and again plays a variety of different bends – before moving up to the 8th fret.

It is around this section of the solo that the vibe and intensity of Vaughan’s playing increases. This bend stacking idea is vital in helping Vaughan build momentum into the second and more intense half of the solo.

If you would like more information on this idea and how to execute it in your solos, I would recommend heading over to the full lesson on the topic, which you can find here – ‘Bend Stacking In The Albert King Box‘.

Otherwise, I would suggest experimenting with this additional note and targeting it – not just with bend stacking – but with a variety of different ideas that help you move between the major and minor pentatonic scales.

SRVisms

The final idea that you can target when playing in the Albert King Box, is to connect it with the first shape of the minor pentatonic with the lick that I illustrate in bar 7 of the tab above:

This is a specific lick that Vaughan uses a lot in his playing to move from the second to the first shape of the minor pentatonic scale.

He plays it in the actual solo on Tightrope (from around the 1.35 minute mark in the track) and it also appears in a number of his other songs.

Not only this, but modern blues guitarists like Kenny Wayne Shepherd – who are heavily influenced by Vaughan – also use the same idea in their playing.

As such, this specific movement helps you to create an SRV vibe in your playing, whilst moving you elegantly between shapes of the minor pentatonic scale.

My improvisation

The majority of my improvisation over the track is based on the ideas that I have covered so far.

I play predominantly in the Albert King Box, cap my phrases in a variety of different ways and add in the major 3rd interval on the high E string. I also target the specific connecting lick that Vaughan uses to move across the fretboard.

Beyond that, there are a few final points that I think are worth noting. Some of these are ideas that I included in my improvisation and others are those that in hindsight I feel are missing and which I would like to have included.

In either case, they will help you to recreate a similar vibe to Vaughan’s original solo in your playing and are important to consider when improvising in this style. They are as follows:

Articulation

As noted in earlier lessons of this course, Stevie Ray Vaughan’s playing is almost totally based around pentatonic scales. The impact and power of his playing comes from how he manipulates these scales, and the techniques he uses to bring life to the notes that he plays.

When playing in an upbeat blues context like this one, Vaughan often articulates in quite an aggressive and intense manner. He picks the notes hard, and uses a wide and fast vibrato to give his notes a stinging feel.

In watching back the various clips in this mini course, I can see that whilst I did replicate this articulation in my play through of the solo, I didn’t achieve this quite as I would have liked when improvising.

So if you would like to add some of the intensity that is characteristic of Vaughan’s style to your own playing, think and try:

- Using a heavy pick attack

- Applying a wide and fast vibrato

- Using the same vibrato on your bends

Additionally, you can target inherently intense techniques in your solo to give your playing a bit more edge. Techniques like double stops and unison bends for example both have an inherently intense sound. As such, targeting them in your solos will also help to add to the overall feel of your improvisation.

Repetition

When it comes to soloing, almost everyone looks at speed as the main mechanism that they have to increase the intensity of their playing. Yet this isn’t true.

In the previous lesson of this course, I discussed Vaughan’s effective use of repetition in his original solo. Far from feeling boring or stale, these moments of repetition create tension and build momentum in the solo.

If you want to do the same in your improvisation, don’t be afraid to repeat notes, short licks or whole phrases. Provided that there is at least some variation in your solo, this repetition will do a lot to help you build momentum and increase the intensity of your playing.

Closing thoughts

To wrap up both this lesson and course, there are three final thoughts that I think are important to note.

The first of these, is that a focus on granularity is critical to your success in blues improvisation.

It is tempting to dismiss some of the ideas here as obvious and then move on. Yet when you start to look at them in more detail and analyse them more closely, two things happen:

Firstly, your awareness of technique and what you and others are doing alters dramatically. This knowledge will increase your confidence as a player and lead to a wide variety of further improvements in your development.

The second is that you realise the power of small changes. Altering a single note, or changing your timing a little can totally change the feeling of your playing. When you combine these small changes together they will transform the sound of your improvisation.

In this way, focusing on details can be liberating. You don’t need to start with a blank slate and can build and adapt on the wonderful ideas that Stevie Ray Vaughan has already created.

Finally, when you are improvising, it is important to remember that you are the one in control.

It is so easy to feel a lack of control when trying to solo. Worries about technique, speed, or trying to connect ideas together can start to cloud your mind.

It is also very easy to start thinking about what you ‘should’ be doing. You can become overly concerned about what Stevie Ray Vaughan does in his solos, what I am doing in mine, or what someone else is doing somewhere else on the internet.

Then before you know it, you are being carried along with the backing track, trying to play at a speed that you find uncomfortable, and to implement techniques that you’ve never before used. You then make mistakes, start to feel frustrated and overwhelmed and you give up.

So, if you feel that you are heading in that direction, just remember – you are the one calling the shots.

If you don’t yet have the technique to play at the speed that Stevie Ray Vaughan does in Tightrope, don’t!

Slow down and improvise at a pace that you feel comfortable. It will still sound great, and the whole process will be much more enjoyable for you. Which brings me to my closing point…

Enjoy the process! 😁

That is what this is all about.

As such, when you are working on crafting your own improvisations, try not to get so myopic about the ideas laid out here that you forget to have fun.

Otherwise, let me know how you get on and if you have any questions at all – please do send them across.

You can reach me on your messenger or in the Blues Café forum whenever and I am always around and happy to help.

Good luck!